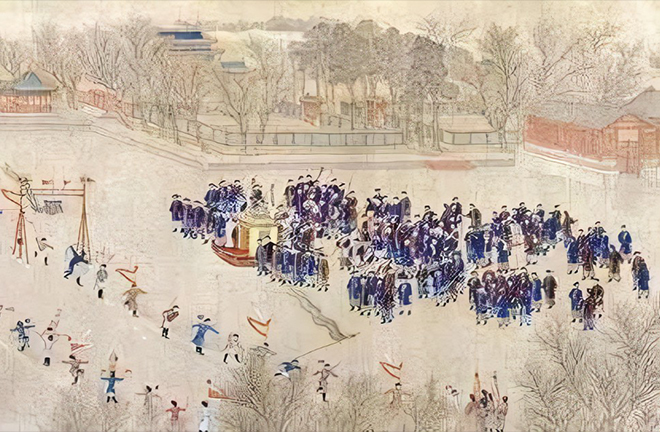

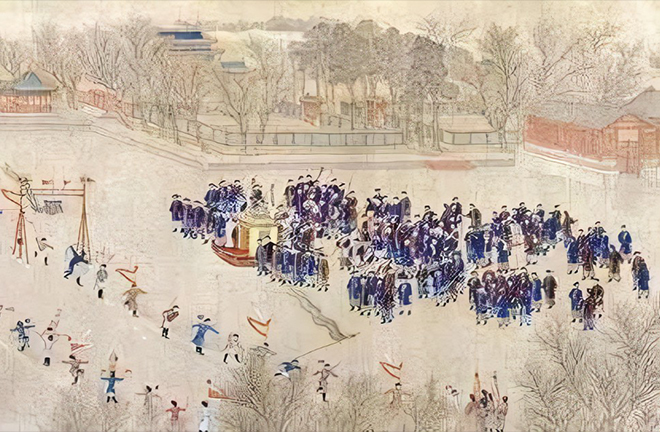

Ice-skating became a traditional sport in the Qing Dynasty. Records indicate that each winter 200 proficient ice-skaters were selected to perform for the court on the frozen royal lake and there were figure skating, ice acrobatics, and speed skating competitions. Photo: A DETAIL OF “ICE-SKATING PAINTING” FROM PALACE MUSEUM

Ice and snow sports have a long history in China. They originate from the Chinese nation’s timeless love for ice and snow, and are an important carrier of national identity, sense of belonging, and national spirit. The modern Olympic Games are a platform where different national cultures interact. As we hold the Beijing Olympics, it is the right time to reflect upon China’s traditional winter sports culture, to retell quintessential Chinese “ice and snow” stories, and explore the essence of cultural diversity. This cultural consciousness will surely become highly valued as the cultural heritage of the Beijing Winter Olympic Games.

Ice and snow in poems

China is a vast country encompassing diverse landscapes. Affected by eastern monsoons, the northern part of the country, especially northeast China, has a humid climate. The average temperature in winter is about minus 20℃, with heavy snowfall and little evaporation. The unique geographical and climatic conditions allow people living here to receive a gift from nature—ice and snow.

Throughout history, Chinese people have voiced a special affection for ice and snow. In the Chinese view, ice represents tenacity, and its crystal clear nature symbolizes an open and aboveboard heart. As Tang poet Wang Changling wrote: “If my kinsfolk in Luoyang should feel concerned,/ Please tell them for my part./ Like a piece of ice in a crystal vessel,/ Fore’er aloof and pure remains my heart.” Ice represents his heart and noble character.

Similarly, snow is representative of purity, peace, and tranquility. White snow often inspires poets. “The white snow, vexed by the late coming of spring’s colors./ Of set purpose darts among the courtyard’s trees to fashion flying petals.” In Tang poet Han Yu’s “Snow in Spring,” our ancestors’ pursuit of harmony with nature is well expressed.

It can be said that the Chinese love for ice and snow is rich and profound. We praise their elegance and purity, while also using them to express our enormous love for the nation and people. As in Chairman Mao’s famous poem, “Snow—To the Tune: Spring in a Pleasure Garden,” he wrote “See what the northern countries show:/ Hundreds of leagues ice-bound go;/ Thousands of leagues flies snow.” Drawing on our rich ice and snow culture and sentiments, “Joyful Rendezvous upon Pure Ice and Snow” has become the beautiful vision for Beijing’s 2022 Winter Olympic Games.

China’s ice and snow culture has formed in a specific geographic and humanistic environment. The Hezhen, Xibe, and other ethnic minorities living in northern China have constantly acquired new knowledge and skills related to snow and ice in their production and daily life, gradually cultivating a lifestyle of co-existence with snow and ice, truly enjoying winter weather, while practicing unique folk customs inspired by snow and ice.

For example, snowfall and icy natural scenes hint at the approach of Nian, Chinese Lunar New Year, which represents reunion, hope, and expectations for spring. In the north, we often see snowmen, ice sailing, ice climbing, dog sleds, horse sleds, ice lanterns, snowball fights, and other winter activities. People enjoy the beauty of life and nature’s gifts through folk customs. Lifestyles of co-existence with ice and snow have shaped our cultural genes, and winter sports have also emerged and gradually expanded.

Origin of winter sports

As early as the Neolithic Period, our ancestors had begun to innovate their means of transportation and tools for hunting on the ice, and constantly improved ways to ice-skate with speed and greater control, in order to obtain basic life necessities in winter.

There are several historical records of ice-skating from the Tang Dynasty (618–907). In the New Book of Tang, there are multiple descriptions of a scene where hunters with wooden boards tied to their feet were rapidly gliding on the ice in pursuit of prey. In the Song Dynasty (960–1279), ice-skating was transformed from a means of transportation and hunting, to a form of recreation. It was recorded in the History of Song that the emperor admired flowers in the royal garden and leisurely skated on the ice. In Dream Pool Essays by Shen Kuo, there were also descriptions of people sliding and running on the frozen river surface. Ice-skating has thus changed from a tool of production and life to a game for members of the court and the general population, which means a relatively independent cultural form of ice and snow sports emerged at that time.

Ice-skating’s development reached new heights during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) with several landmark historical events. First, Emperor Nurhachi held an extraordinary series of ice games in 1625. These were the first government-sponsored ice games in China’s history. When the Qing court moved to Beijing, ice-skating gained political functions, it demonstrated imperial power and served as a prayer for lasting peace. Ice-skating was designated a national custom, with special government units responsible for organizing events, maintaining skates, and training the skaters.

As ice-skating developed, there were also a range of literary and art works which delved into the theme, including Emperor Qianlong’s poems and Giuseppe Castiglione’s painting. With high cultural and artistic value, they played an important role in promoting the spread of ice and snow culture among scholars and through society as a whole.

In the meantime, ice-skating became seen as a competitive sport. Either in the royal court, or among the common people, ice-skating was much loved and endowed with special functions, such as driving away evil and illness, due to the catchy phrase it formed in Chinese.

As for snow sports, an ancient cave painting showing human figures sliding on small platforms over slopes, corralling a herd of animals, was found in Altay, Xinjiang. Historians estimate its antiquity to range from 5,000 to 10,000 years. Thus, Altay City has been dubbed “the ancient cradle of skiing.”

In the Classic of Mountains and Rivers, skiing scenes are included which feature nomadic people who lived south of Lake Baikal, towards Mount Altay, where people wore fur from the knee down and made special boots with snowboards. From the Sui (581–618) and Tang dynasties to the Qing Dynasty, materials which show people riding on wood to chase deer in the snow, or people dragging snow carts, and dogs pulling sleds, were abundant. There are even descriptions of skis with sharp wings in the front, and horse fur on the bottom of the skis, to reduce friction downhill and increase resistance uphill. From the sophisticated equipment making technology and movement control skills, we can see that people have gradually obtained a rational understanding of the sport.

Generally speaking, people ski and skate out of necessity for labor, and over time these ice and snow activities have gained entertainment value as part of the folk customs, military values, and political values of national celebration. Compared with skating, skiing has higher requirements in terms of equipment, venues, and athletic skill. At that time, the productivity level and social development limited the wide spread of skiing and hindered its popularity.

2022 Winter Olympics

Nowadays, the modern Olympic Games have become a cultural interaction platform which moves across nations and across time. The Chinese winter sports culture, especially our traditional culture, should take advantage of this platform to carry out cross-cultural dialogue and communication with other cultures.

First, it should be recognized that different winter sports cultures are intrinsically linked. Winter sports originate from nature, and people’s production and life experience, so their cultural roots are interlinked. From the perspective of the source culture’s evolution, they are the products of integrating nature and human civilization.

Second, different winter sports cultures follow values, aesthetic tastes, and ways of thinking that are in line with their respective national characteristics, reflecting the national character, spirit, and judgment of truth, goodness, and beauty.

Third, different winter cultures all show the same spiritual temperament. When people watch sports, they can appreciate the spirit of fearless persistence and endurance in ice and snow, and feel the wisdom, creativity, and beauty of athletic human beings.

Fourth, different winter sports are very similar in technical expression forms. For example, China’s “ice skating chair” or “plank” and the West’s “ice sled.”

In addition, it should also be acknowledged that there are significant differences between different winter cultures. For example, under the influence of the ancient Greek Olympic culture, Western winter sports emphasize competition more, and development of individual potential and self-expression, so the sports tend to be more competitive, aggressive, and adventurous. Chinese traditional winter sports dwell on the spirit of harmony, pursue the harmonious coexistence between man and nature, and emphasize the natural expression of human nature.

Another point, is that supported by industrial civilization, Western winter sports are more modern, scientific, and standardized, with a main purpose of serving leisurely life and promoting cultural transmission. Traditional Chinese winter sports are the products of ancient Chinese fishing and hunting cultures in the north. The hand-made equipment is mainly used to improve the efficiency of production and life. Cultural transmission functions are greatly affected by the region, season, and ethnicity.

In summary, we should revisit the essence of Chinese winter sports culture, actively share China’s “ice and snow story” with other cultures at the Beijing Winter Olympics, and better contribute Chinese philosophy and wisdom to the Olympic Games, on the basis of cultural consciousness and cultural confidence, to demonstrate our iconic cultural heritage for the Beijing Winter Olympics.

Li Shuwang is a professor from the PE Department at Renmin University of China.

Edited by YANG XUE