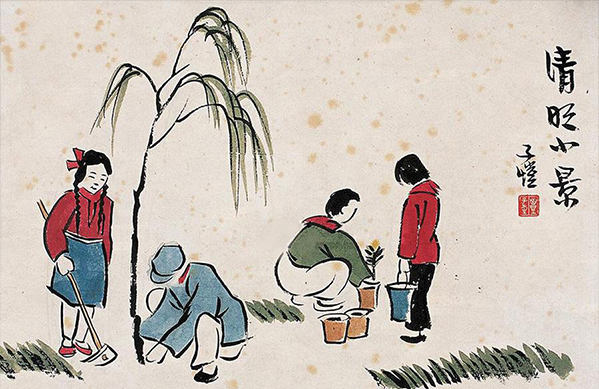

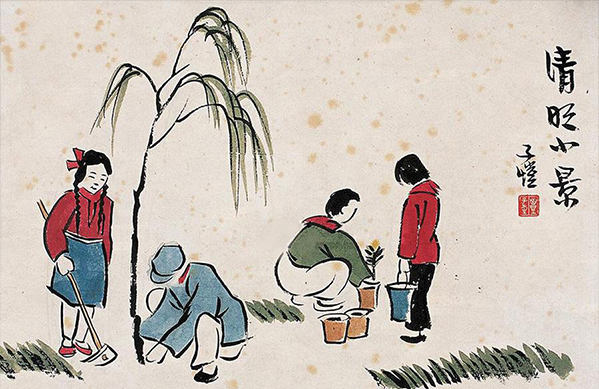

“A Scene at Qingming Festival” by Feng Zikai Photo: ARTRON.NET

The Qingming Festival, or Tomb-Sweeping Day, falls on the first day of the fifth solar term (the 24 solar terms divide a year into 24 segments based on the Sun’s position in the zodiac) of the Chinese lunar calendar. The term qingming means “bright and clear” in Chinese, indicating that the days around the festival feature bright skies, fresh air, and a bracing breeze. For the Chinese people, it is a day of mixed emotions and traditions. Around the festival, the Chinese often worship their ancestors, wear willow branches, take spring outings, fly kites and, in certain places, eat qingtuan, a seasonal dessert made from glutinous rice mixed with pounded mugwort.

A day of gratitude

An essay by the Chinese historian Yan Chongnian explores the multiple meanings of the Qingming Festival.

“The Qingming Festival is a festival of diverse cultural significance. It embodies at least six different connotations:

First of all, the Qingming solar term is one of the 24 solar terms. The Qingming solar term indicates a bright and refreshing season when everything comes back to life.

The festival also provides instructions for agricultural production. ‘Plant melons and beans around the Qingming Festival.’ This old saying indicates that Qingming is a crucial time for plowing and sowing in the spring.

One or two days before the Qingming Festival, is the Hanshi Festival, or Cold Food Festival. This day is connected to the story of two historical figures in the Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BCE)—Jie Zitui and Duke Wen of Jin. Eating cold food on the day of Qingming used to be a ritual ceremony. As time went by, the Hanshi Festival gradually merged into the Qingming Festival.

With peach blossoms in full bloom, many people prefer a spring outing during the Qingming Festival.

The Qingming Festival is also a day of various traditions. Sheliu, or willow-shooting, was an ancient game in which pigeons were put into gourds and the gourds were hung on a willow tree. Players shot the gourds with arrows, so as to free the pigeons inside when the gourds fell onto the ground. The winner was the one whose pigeon flew the highest on its release. Sheliu was a festive activity which combined military training with entertainment. The Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking written by Tun Li-Ch’en (1855–1911) recorded that during the Qing Dynasty, playing on swings was a popular activity in Peking on the day of Qingming.

The last connotation of the Qingming Festival lies in the practice of tomb-sweeping.

In short, the Qingming Festival embodies both the reverence of honoring ancestors, and the bliss of savoring the springtime. It is a day both for mourning the deceased and for celebrating new beginnings and the changing seasons.

Tomb-sweeping reflects an important concept for Chinese people—gratitude. The Qingming Festival is ‘China’s Thanksgiving Day.’ The ethical and cultural value of this day lies in the sense of gratitude.

There is a story about the origins of the Qingming Festival. According to the ancient text Shiji, or the Records of the Grand Historian, Chong’er (697–628 BCE), who was also known as Duke Wen of Jin during the Spring and Autumn Period, was forced to live in exile for 19 years before he came to the throne of the Jin State. When he was in exile, Jie Zitui was among those who followed him through all his difficulties. It is said that one day, Chong’er was starving and close to death. Jie Zitui cut a slice of muscle from his own leg and served it to Chong’er. When Chong’er eventually returned to the Jin State and seized the throne, he rewarded all his loyal followers. However, Jie either refused or was passed over for any reward. He then retired to the forests on Mt. Mian, in what is now Shanxi Province, and finally passed away on that mountain. Legends said that Chong’er named the Mt. Mian ‘Jie’ to express his gratitude.

In fact, the tradition of tomb-sweeping and commemorating the deceased during the Qingming Festival predates this story. The Qingming Festival is a day to commemorate and express gratitude to ancestors, the brilliant people of the past, and martyrs.”

Family rituals

Praying and making ritual offerings to ancestors and deceased family members is the most important family ritual during the Qingming Festival. The renowned Chinese writer Ye Shengtao (1894–1988) reflected on the ways his family practiced these rituals in one of his essays.

“When the day of Qingming came, we followed the old customs to worship our ancestors. We usually laid three tables [for ancestors to have dinner] during the day. However, our house in a longtang (a lane) in Shanghai was too small to seat three tables. We had to lay two tables at first, and later replace them with the third one.

After burning incense and offering drinks to our ancestors, it was time to kneel down in front of the ancestors’ shrine or altar. I seldom exercised. My knees became stiff even though I was just over 40 years old. When I knelt down, I thought about nothing except the feeling that my knees were seizing up. Among the ‘seated ancestors’ (the spirit tablets on the altar to designate the seats of past ancestors), my clearest memories were of my father and uncle, because they passed away most recently. However, I couldn’t imagine how they crammed the two chairs with a dozen ancestors, eating and drinking at the table together. I had a sister who died at age 11. She would have been 38 years old this year. My mother would always prepare fruit for her during the ritual. I couldn’t imagine how she would peel oranges or spit peach-pits either.

My father and uncle, when they were alive, performed the ritual of kneeling in quite a different way. They looked solemn. After kneeling and performing the kowtow three times , they gently touched their heads to the ground a dozen times, as if praying silently there. Then they stood up and left respectfully. They had been accustomed to these ritual practices concerning the traditional belief that the deceased should be served and honored as if they were alive.

Sometimes, kids practiced the kowtow with me. I let them go if they didn’t want to do it. Their favorite thing was burning zhi ding, which was made of joss paper folded into the shape of gold ingots. They slowly put zhi ding into an enamel bowl, and watched as it was eaten up by fire, turning into ashes. It replicated the atmosphere of stoking a brazier in winter. For kids, a festival indicates sumptuous meals, and each festival is like a game, so that they get to play several times every year. They couldn’t imagine how our ancestors would flock into our house, seated on the left and right of the altar according to the zhao-mu system (a traditional arrangement of spirit tablets), and returned to the afterworld with money (zhi ding) after enjoying the grand meal.”

Celebration of nature

Many painters throughout history have left works of art which portray traditional events common to the Qingming Festival. In his work, Feng Zikai (1898–1975), an influential artist, depicted people enjoying a cheerful Qingming Festival in nature. The worship of nature could also be found in his writings.

“Tomb-sweeping is a tradition of the Qingming Festival. It should be a sad event. When I was young, however, going to visit tombs was quite a delight. Some people prefer to take a spring outing when attending Buddhist events. For us, going for tomb-sweeping was also an opportunity to embrace the springtime.

During the three days around Qingming, we went to visit tombs every day. On the first day, which was also the Hanshi Day, we went to visit the ‘Tomb of Yangzhuang’ in the afternoon. This tomb was about 2.5-3 kilometers away from our town. We had to walk all the way there. Elders and young children usually didn’t go on the tour. I started to take part when I was seven or eight years old. Uncle Maosheng shouldered a carrying pole loaded with offerings and walked ahead. We followed him, picking peach blossoms and broad beans along the way. What a pleasure!

We took a break after arriving at the graveyard. Then Uncle Maosheng would borrow a table and two benches from a nearby farmhouse. We put offerings on the table and then performed kowtow. After all was done, it was time for fun. We ate sweet wheat pastry or zongzi, a traditional Chinese dessert made of sticky rice. Some picked broad bean stems and made them into flutes.

As the tomb-sweeping practices concluded, Uncle Maosheng would return the table and benches to the farmhouse, together with two pieces of sweet wheat pastry and a pile of zongzi as a gift. Then we left for home at sunset. Near the ‘Tomb of Yangzhuang’ was a giant pine tree. By the pine tree was a pond. My father called this scene ‘a beauty looking into the mirror.’ It has been decades since I went to visit the ‘Tomb of Yangzhuang.’ I wonder whether the ‘beauty’ is still there and looking into the ‘mirror.’ When I close my eyes, my mind flashes back to those scenes from the past.”

Edited by REN GUANHONG