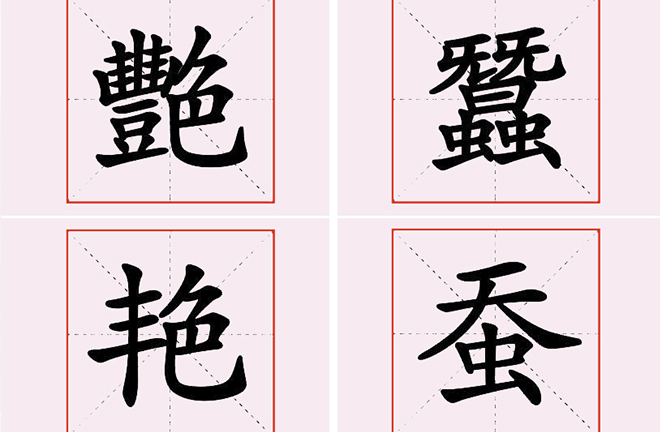

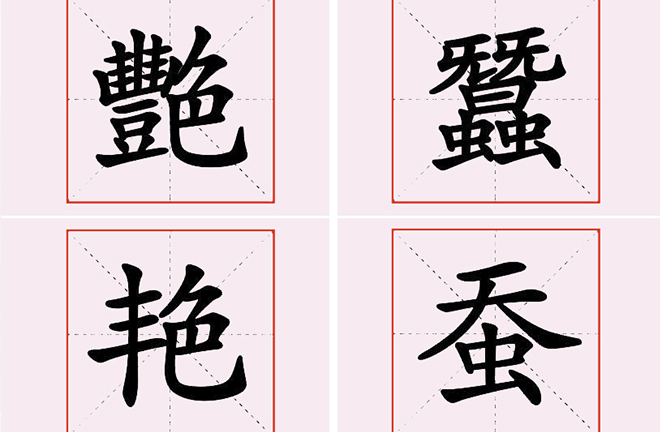

Yan (left, meaning colorful) and can (right, silkworm) each in traditional and simplified forms. These are two examples raised by Wang Yiqin in Introducing Simplified Chinese. Wang believed that the complexity of traditional Chinese largely accounted for the high illiteracy rate in the past. Photo: CSST

On Aug. 21, 1935, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China published the table of first batch of simplified characters (hereinafter referred to as “the Table”) consisting of the simplified versions of commonly-used 324 characters. The Table became the first officially released word table of simplified Chinese characters, and although it was suspended by the government soon afterwards in early 1936, it still triggered a hot debate in both society and academia.

Bound to appear

Since the Table was released, many people began to rethink what they knew about the shape and structure of Chinese characters. Some scholars compared Chinese characters with other writing systems in terms of their common development pattern, and eventually concluded that simplified Chinese characters were inevitable. In Dec. 1935, Yishibao (The Social Welfare), a Tianjin-based newspaper, published an editorial titled “Developing Simplified Chinese is Imperative.” The article observed the reality surrounding simplified Chinese characters, and concluded that by examining and revising simplified Chinese, the Ministry of Education was keeping up with the times.

Similarly, scholar Zhang Wenzheng reached the same conclusion in one of his articles, which discussed the process of traditional Chinese characters’ simplification, and eventually concluded that promoting simplified Chinese was visionary. Gu Liangjie, Lu Rulin, and Li Zhengfu also believed that Chinese simplification fits the rules for language development, since many languages in the world have also followed an iterative pattern, evolving from difficult to simple.

Some scholars compared word tables of simplified Chinese from various eras in order to show how scientific it was to simplify characters. In “On Simplified Chinese and Administrative Efficiency,” Zhang Dinghua wrote that since 1916, many scholars advocated for the simplification movement, and some even compiled collections of these words, including A Glossary of Popular Chinese Characters since Song and Yuan Dynasties by Liu Fu, Simple Explanations on Words by Hu Huaichen, Studies on Frequently Used Simplified Characters by Xu Zemin. Zhang also believed that publishing the Table was a move which accepted and acknowledged the simplified words that had already been widely used.

By assessing the functions of a writing system, some scholars verified the necessity of using simplified characters. Zhang Dinghua also pointed out that writing was formerly exclusive to the upper class, so its simplification and reformation could only be enacted by a monarch and carried out by scholar officials.

The writing system was only popularized and made accessible to all social classes in modern times. Since traditional characters were too complex to use, a simplification movement was initiated from the grassroots, and many simplified Chinese characters began to come into widespread use. “On Promoting Simplified Chinese,” which was published in North China Daily in Aug. 1935, wrote that words are tools for us to pass on ideas and gain knowledge, and it was necessary to sharpen our tools in order to drive civilization, and simplified Chinese serves exactly that goal.

However, some other scholars suggested that the country should skip simplified characters and develop the pinyin romanization system for Chinese instead. Zhi Guang wrote that although simplified words are easier to write, they are exactly the same as traditional Chinese characters in terms of pronunciation and memorization, and it is impossible to economize all Chinese words into two or three strokes. That is why Zhi Guang argued for a romanized writing system for Chinese. Zhang Yongnian also believed that simplified words lacked range, therefore it was inevitable that pinyin would replace Chinese characters.

These scholars failed to see that characters’ vitality would be enhanced once their strokes were trimmed. Sha Xuan refuted the suggested replacement of characters with pinyin in Simplified Chinese at the Crossroads, calling the suggestion ill-founded.

Practical

The biggest difference between simplified and traditional Chinese is the number of strokes. Whether or not the relatively younger Chinese words can replace their ancestors depends on their practicality.

In Dec. 1935, Kang Benchang wrote that students at the time had already started to transcribe and use simplified characters from the Table. Students decided simplified characters were easier to write and time-saving. Similarly, many scholars argued that simplified words were easier to write and recognize, thus helped people develop functional literacy skills.

Some scholars pointed out that simplified Chinese can promote functional literacy. Xu Zemin believed that simplified words fit society’s demands by helping the lower class to memorize and write the characters more easily, which made universal education possible. Likewise, in “How Simplified Chinese helps the Chinese Learn to Read,” Lei Zhen suggested that it was necessary to use phonetic notation and simplified characters when teaching people how to read and write. Zhou Diqin proposed that Chinese teaching materials adopt simplified Chinese as their standard text system.

Some scholars even designed experiments to test simplified Chinese’s effectiveness in promoting literacy. For instance, Shen Youqian measured the efficiency of applying words listed in the Table. Yang Junru also carried out an experiment, which helped him conclude that simplified characters are a lot easier to recognize, transcribe, and write from memory, which therefore eases children’s learning burden.

It should also be noted that the simplification movement still encountered obstacles. There was a transition phase from the use of traditional to simplified Chinese. Occasionally, the shapes of some simplified characters did not correlate with their meanings as well as their traditional counterparts. Consequently, some scholars considered simplified characters not helpful enough, and opposed or disregarded the idea of popularizing simplified Chinese.

There were two common objections to the movement. First, simplified characters meant that people may have to learn the same words twice. This point was well explained by Mao Yan, who believed that simplified characters could only go so far to reduce the difficulty of writing. The second major concern was that there was not a well-structured system for simplified characters, which made them harder to remember. Jing Chen said in “On Education Ministry’s Promotion of Simplified Chinese” that learning simplified Chinese is often a process of learning one word while forgetting another.

Generally speaking, simplified Chinese is easier to learn, thus was embraced by many organizations once the Table was released. In “Simplified Chinese and Administrative Efficiency,” Zhang Dinghua said that using simplified words in paperwork can enhance administrative efficiency. Fang Zhi pointed out that using simplified characters was also helpful for journalism.

Cultural

The Chinese language is an important carrier of the country’s culture and academic achievements. Shifting from traditional Chinese to simplified Chinese may bring about changes to not only our words but also our culture and academy, which was another contentious point for scholars in the Republican era (1912–1949).

Some scholars believed that adopting simplified characters would hinder cultural inheritance and academic development. Ke Yude pointed out that simplified Chinese was likely to make it difficult for Chinese culture and history to be passed on to future generations. Other scholars were concerned that simplified words may divide Chinese culture into two parts: one under simplified Chinese and another under traditional Chinese.

Still, more scholars at the time believed that simplified Chinese could carry culture and facilitate academic progress just as well as traditional characters.

To respond to the concern that “younger generations will not be able to read ancient books because they were taught simplified Chinese,” Gu Liangjie argued that there are two types of students: those who will continue advanced study and those who will not. He believed that the former kind would have no trouble reading ancient books, because they can use references (such as the Table itself) to compare traditional and simplified Chinese. Li Zhengfu also pointed out that naturally, students who are interested in traditional Chinese or are well-educated will teach themselves traditional Chinese.

Scholars also feared that simplified characters would eliminate traditional Chinese, and since simplified characters are not as beautiful as traditional characters, the aesthetic beauty of calligraphy would be lost. Gu believed that the two types of characters could coexist in harmony. Also, people can still explore the beauty of simplified Chinese by writing them in running hand, clerical script, etc.

As to whether or not simplified Chinese would affect cultural inheritance and academic development, Lu Rulin believed the reform of Chinese characters was essential to academic progress, and the promotion of simplified characters was an important starting point.

Generally speaking, many scholars during the Republican era supported the simplification movement, and they were proven visionary considering simplified Chinese’s wide use in modern times. Their valuable comments, as well as the perspectives and methods they later adopted, helped the work of further simplifying traditional characters after the founding of the PRC in 1949, and continue to inspire us in standardizing the language in the future.

Sun Jianwei is from the International School of Chinese Studies at Shaanxi Normal University.

edited by WENG RONG