Literati painting: What does it do?

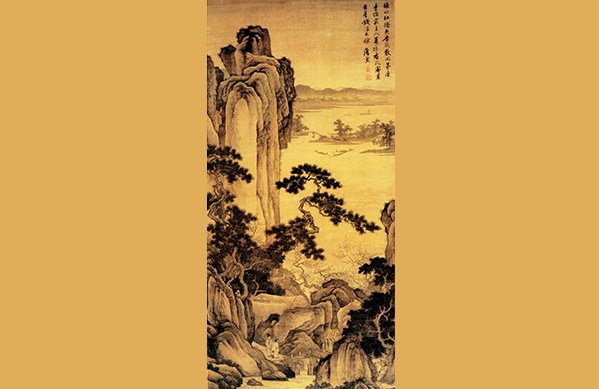

“Apricot Blossoms, Thatched Houses” by Tang Yin (1470–1524), a representative literati painter in the Ming Dynasty Photo: FILE

Literati paintings are an advanced art form in China. Strictly speaking, what distinguishes the literati paintings from other paintings are the ideas that they convey, rather than the skills, techniques they apply. This makes literati paintings quite different from paintings serving practical purposes, such as court paintings and paintings by skilled artisans.

A great art form

Before the Tang Dynasty, the practical style had dominated Chinese painting while literati paintings were rare. Practical style paintings aimed for a variety of functions, characterized by technical finesse, certain patterns and less personal expression. Most painters of this form were court painters and artisans.

There was a significant change in painting trends during the Song Dynasty, after a group of literati elites represented by Su Shi (1037–1101) engaged in painting. Their paintings were supposed primarily to reveal their aesthetic cultivation and express their personal feelings rather than demonstrate professional skill. Su Shi was also known for his comments on painting. He used to paint bamboo with cinnabar. When his companions noticed that there was no red bamboo, Su asked them: “People usually paint bamboo with ink. Has anybody ever seen black bamboo?” This rhetorical question reflected Su’s awareness of the nature of art that art was not a direct copy of the real world. Su also said, “Appreciating literati paintings is like looking at galloping steeds of the world: one must choose only those that work well in both structure and vision.” The literati painters’ aspirations to freely express their feelings through painting showed a sense of modernism.

Criticism of literati painting

Literati painting attracted widespread criticism since the early 20th century, mainly during the period of the resistance against Japanese aggression, and the period from the 1950s to 1970s. The main reason was the alleged lack of practical function of literati paintings. Some argued that literati painters didn’t pay much attention to professional painting skills, which made Chinese painting unable to compete with Western painting. Others considered literati painting a product of an ivory tower—it failed to objectively render the real world—an art form useless for promoting revolution and social construction. The renowned Chinese philosopher Kang Youwei (1858–1927) blamed the decline of Chinese painting on literati painters as they laid too much emphasis on capturing the inner spirit of their subjects rather than describing their outward appearances. The prominent writer Lu Xun (1881–1936) compared literati paintings to doodles. He wrote that literati painters “draw several curves and call them leaves, but the audience cannot tell whether they are reeds or flax; with a horizontal stroke they declare the portrait of a bird, but who can tell what kind of bird it is?”

Today, people have come to realize that simply admiring Western realism while disparaging literati paintings is not a correct way of thinking. However, this aforementioned criticism was based on the social context of the time. The first half of the 20th century was characterized by China’s decline and profound social transformations. In front of the modernized Western powers, many Chinese people began to question all the elements of Chinese tradition, including painting. Furthermore, saving China and leading it towards national prosperity was the top priority for all the Chinese people. Critics considered paintings a political and revolutionary campaign tool and stressed its propaganda value. This was why Lu Xun highly praised the woodcut prints created by Kathe Kollwitz, a German artist whose expressionistic works portray human suffering. Another reason for literati paintings’ loss of popularity was their poor quality. Since the middle Qing era, literati paintings tended to be conservative and stereotyped. Most of them neither inherited the essence of the literati traditions nor did as well as Western art in terms of realism.

Social significance

The art form of literati painting has been thriving in China for over 1,000 years. In fact, this art form has been socially significant.

Different industries affect the world in different ways. It is easy to understand how a manufacturing industry contributes to society. However, some industries, such as art, affect society in a more secretive but positive way. The value of art has been discussed during the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE). As shown in historical documents, views of music were expressed by Mozi, a radical opponent of Confucius, and Xunzi, a practical representative of Confucianism. Mozi judged music in terms of a negative utilitarianism and regarded it useless. In his view, music promotes wastefulness and deprives social production of time and energy. In contrast, Xunzi argued in terms of a positive utilitarianism that explicitly favors music. In his mind, music is effective not only for personal relaxation but also socially for harmonizing human relations. Xunzi’s view was widely accepted by later generations.

The social significance of literati paintings can be discerned from certain famous comments on landscape paintings, as most literati paintings are of landscapes. The Northern Song artist Guo Xi (c. 1000–1090) wrote, “Contemplation of such pictures arouses corresponding feelings in the breast; it is as if one had really come to these places…without leaving the room, at once, he finds himself among the streams and ravines.” He noted that humans have an innate attachment to nature. However, not everyone can visit nature any time they wish. The function of landscape painting is to serve as a substitute for nature, allowing the viewers to wander in their imaginations within the landscape. The 20th century Confucian scholar Xu Fuguan (1903–1982) believed that art reflects reality in two ways—either directly depicting and highlighting reality (known as shuncheng, an example would be the Dada movement in the early 20th century) or criticizing the reality (known as zixing, or introspection). As Xu asserts, Chinese landscape painting is intended to represent spiritual freedom, which leads the eye into infinity and brings vitality back to life as the real world is driven by fame, wealth and other desires. This is a way of zixing. Xu compared Chinese landscape paintings to a cold drink in summer. He wrote that people need art that cools them down as they live under great stress caused by fast-paced living.

The article was edited and translated from China Art Weekly. Fu Zhen is the deputy curator of Quzhou Cultural Center.

edited by REN GUANHONG