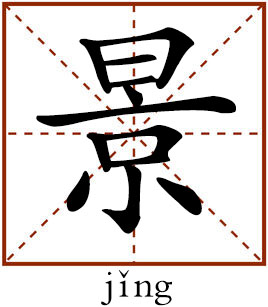

Scenery

This character usually refers to scenery or circumstance.

良辰美景奈何天

liáng chén měi jǐng nài hé tiān

Liang chen refers to good times and mei jing is beautiful scenery. Nai he tian is usually a time of helplessness. A translation of this term by Cyril Birch (Bai Zhi) is: “ ‘Bright the morn, lovely the scene,’ listless and lost the heart.”

This is a famous line from the The Peony Pavilion by Tang Xianzu (1550–1616), a Ming Dynasty playwright honored as a Shakespeare in China. The Peony Pavilion is a romantic tragicomedy. Du Liniang is the single daughter of the magistrate of Nan’an in the early days of the Southern Song Dynasty. A stroll in the garden in a bright spring day rouses Du’s aspirations for love. She takes a nap near the Peony Pavilion and dreams a strange dream, in which she falls in love with a romantic scholar. Haunted by the dream, she falls ill and finally dies. During her last days, she draws a self-portrait as a keepsake for the scholar. She is then buried in the garden according to her last wishes. Not long afterwards, the young scholar Liu Mengmei comes and stops over in a room near the garden. He happens to pick up Du’s self-portrait and is attracted by her grace. In his dream, Du tells him that she can be revived. The lovers overcome all difficulties, transcending time and space, life and death, and finally come together.

The term is derived from the section when Du enters the garden and bathes in the spring sunshine: “The flowers glitter brightly in the air,/ around the wells and walls deserted here and there./ Where is the ‘pleasant day and pretty sight?’/ Who can enjoy ‘contentment and delight?’” She links the swift passage of spring to the swift passage of her youth and regrets that she is wasting her youth in her chamber.

In his inscription to this play, Tang writes, “To be as Du Liniang is truly to have known love. Love is of source unknown, yet it grows ever deeper. The living may die of it, by its power the dead live again.” This “love” in Tang’s interpretation is the genuine affection felt by human beings, in direct opposition to the “ethics” inherent within feudalist morality. Song and Ming dynasty ethics highlighted the preservation of ethics instead of human desires, while Tang’s view on “Absolute love” is a reaction to these ethics.

edited by REN GUANHONG