Quarantines control epidemics from ancient China to today

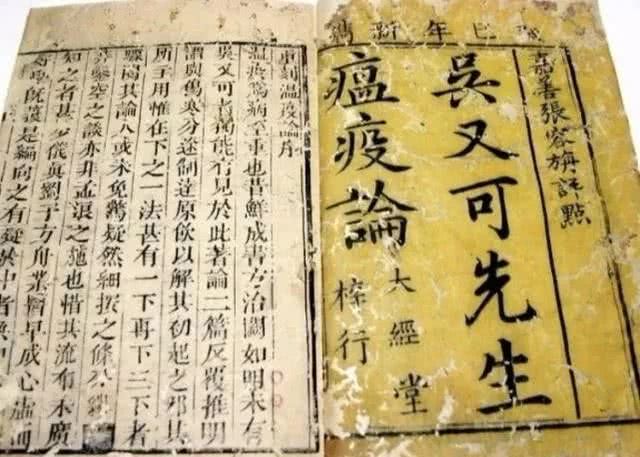

Epidemic records in an ancient book Photo: FILE

This Spring Festival in the year of Gengzi, for every Chinese person, has been quite unique and unforgettable. The COVID-19 epidemic has ravaged the city of Wuhan and spread nationwide. Many places in China have initiated the “highest-level response” for the prevention and control of the contagion, both in urban and rural areas. Everyone has kept indoors and rejected visitors. “Quarantine” has also become one of the most discussed words of the year.

Looking back through the annals of history, we can see human civilization surging forward with great momentum. From the era of crawling to that of walking upright, from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age, human beings have marched from savagery to civilization. Yet since the beginning of recorded history, every major outbreak of an epidemic has had to be dealt with in the most primitive and ancient method—quarantine (in Chinese, geli). There seems to be no better way. In ancient China, geli was also called lijian (isolation). The patients were quarantined mainly in the form of a separated shelter, for example, in a temple or a temporary shack built on open land. These places were used for enforced isolation.

If the epidemic was serious, the authorities would use mandatory methods of isolation, for example, blocking access to the epidemic areas, sending troops to set up guard, and forbidding the free flow of people to prevent the further spread of the epidemic. This has become a strategy also adopted today.

The “Annals of Emperor Ping” in the History of the Former Han says that when plagues pervaded, those infected were isolated in empty houses, visited by doctors and provided with medicine. At the same time, officials distributed free medicine to those afflicted and provided medical services. According to the text written on bamboo slips from the Shuihudi Tomb of the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE), when an epidemic occurred, if people found anyone around them with the signs of infection, they had to keep their distance and report to the government. Once officially diagnosed, the patient would be forcibly quarantined in a designated place, called the House for Pestilence, so as to cut off the source of contagion. During the prosperous period of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) when the nation was strong, many medical charities appeared in the capital Chang’an (today’s Xi’an). There were both officially and privately operated Recuperation Houses and Therapy Houses. The temples also ran similar places called Beitian Houses and Futian Courtyards to specially treat or quarantine patients. By the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1276), Anji Houses had been established by the government in local places nationwide. Once an epidemic broke out, a quarantine was conducted to avoid the spread of infection depending on the severity of the disease, and doctors needed to make a record of each patient’s condition. During the Ming and Qing dynasties when leprosy raged, hospitals for leprosy treatment were consecutively established in many places in South China. Those patients accommodated could get married, give birth to children and live a free life inside the quarantine zone.

Of course, in the case of an epidemic, quarantines were not always successful. It was not surprising that the measure almost always encountered a variety of criticism or resistance. For example, it was recorded that in the Jin Dynasty (266–420), if a courtier’s family was infected with the plague with more than three family members infected, even those family members not infected were not allowed to enter the palace of the court within 100 days. This seemingly effective isolation method was, however, ridiculed by the people at that time and was considered “inhuman.”

In fact, the history of human development is also a history of struggle with various diseases, and records of epidemic diseases can be found everywhere in the ancient classics. Based on various sources of reliable historical data and using statistical methods, The History of China’s Famine Relief, authored by Deng Tuo and published by the Commercial Press, for the first time comprehensively discusses the number of epidemics in past dynasties. According to incomplete statistics in the book, epidemics occurred in the Zhou Dynasty once, the Qin and Han dynasties 13 times, the Wei and Jin dynasties 17 times, the Sui and Tang dynasties 17 times, the northern and southern Song dynasties 32 times, the Yuan Dynasty 20 times, the Ming Dynasty 64 times, and the Qing Dynasty 74 times. One of the most serious death tolls took place in 1232, the first year of the reign of the Kaixing Emperor during the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234). In that year, the epidemic struck Bianjing (today’s Kaifeng of Henan Province) and it is recorded that “within 50 days, more than 900,000 corpses were lifted out from the city gates, and numerous dead could not afford to be buried.” According to the History of Disasters in Beijing, there were 12 years during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) and 17 years during the Qing Dynasty (1636–1911) in which plagues attacked Beijing. During that period, epidemics occurred in Beijing every year, but they did not spread widely. A historical book compiled by Bao Yangsheng, a scholar from the Qing Dynasty, writes that “in February of the 16th year of the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor, a type of epidemic struck Beijing—the name of the disease is nodular pestilence. Afflicted by the plague, people and ghosts were mixed together.”

Looking across globally, there have been even more terrible epidemics, with calamitous impacts. Cholera, bubonic plague, typhus, etc., all have brought great disasters to mankind.

In fact, it has not been long since viruses really entered human vision. Though sharing this planet with humans, viruses have existed far longer. Data shows that the birth of life on the earth began about 3 billion years ago, with viruses as the forerunners of the most primitive life forms. One news article says that according to scientists’ calculations, there are 100 billion virions in every liter of seawater, and there are about 1031 virions in all the oceans on earth, which is a staggering number, 15 times more than the number of all the fish, shrimp and other marine life in the oceans combined. These viruses weigh as much as 75 million blue whales, and if they were lined up in a row, they would be 42 million light-years long, much longer than the entire galaxy system. It is unknown how scientists measured the data, but it suggests that viruses are ubiquitous on the earth.

Living in the garden of the earth, people always assert themselves “the lord of all creatures.” But in the face of nature, humanity is sometimes very vulnerable. Once unknown viruses enter the scene, it’s like opening Pandora’s box. These invisible, intangible, totally strange and bizarre “little guys” can exact a heavy cost on humanity.

As Mencius said, “If we do not abuse the farming season, the grain will forever be abundant; if we do not catch fish in the pond with a fine net, the fish and turtles will never be eaten up; if the trees are cut down at a certain time of the year, there will be no shortage of wood.” The philosopher Kant also said that there are two things in the world that are venerable: the stars above us and the moral laws within us. Having been successively taught the most grievous lessons, we should learn to respect nature, to protect nature and to care for all living things, which is in fact the way to protect ourselves.

This article was edited and translated from Guangming Daily.

edited by BAI LE