Spring Festival in the eyes of Chinese literati

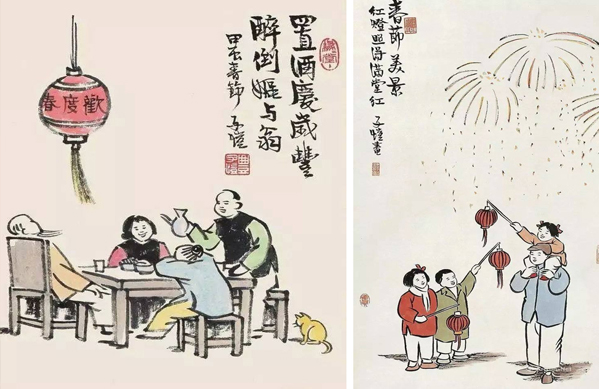

Paintings by Feng Zikai depict how the Chinese people celebrated Spring Festival in the past. Photo: FILE

Feng Zikai (1898–1975) was an influential Chinese painter, pioneering cartoonist and essayist of 20th-century China. Born in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province, a city in the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, Feng’s memory of the Spring Festival in his hometown epitomizes the festive traditions and customs of southern China:

“Offering sacrifice to the Kitchen God falls on the night of the 23rd day of the twelfth lunar month, because the Kitchen God, also known as Zao Jun, usually goes to report to the emperor of heaven about the activities of each household during the past year on that night, and returns on the last night of the twelfth lunar month. On that day, a mixture of sticky rice and azuki beans was cooked in every household, first offered to the Kitchen God, and then shared with the whole family. At dusk, after dinner, my father in formal attire bowed before the stove, then the whole family prostrated ourselves before it. After the prostration, the plaque of the Kitchen God was ‘invited’ into a special litter, which was made of red and green paper, with a couplet flanking it reading, ‘Take nice words to heaven; bring blessings for the household.’

We hung a string of paper-made gold ingots on the litter, and smeared malt sugar on the lips of the Kitchen God for it was believed that the Kitchen God could not speak of bad deeds with his mouth glued together with sweets. Carefully and solemnly, my father took the litter outside for burning, during which we had to save a paper-made gold ingot from the fire. People believed that preserving this would be an omen for a real gold ingot in the coming year. After that day, every household began to cook rice cakes. In order to cook big, sticky rice cakes, we needed extra people to help.

The Spring Festival celebrations started on the night of the 27th day. In the daytime, families were busy preparing offerings—pig’s head, chicken, fish and other meat courses served on big plates. After supper, two tables were attached together, covered with red cloth. Offerings, a huge tin censer and candlesticks were put on the table, surrounded with rice cakes. The living room where the tables were presented was shared by three families. We and the other two families offered sacrifices to the bodhisattva together. The room was ablaze with light, the smoke of incense curling up. What a feast!

We usually stayed up all night on the last day of the year. Our family’s shop was decorated with kerosene lamps and sui candles (a pair of candles that burn all night). At the evening banquet, all the family’s tableware was presented on the table, to wish the family new arrivals in the New Year. My mother distributed hong bao (lucky money in a red envelope) to the younger generations of the family. I got 0.4 yuan, which was spent on fireworks.

On the first day of the lunar New Year, we were busy receiving guests who came in the spirit of bai nian (paying New Year visits). The streets were crowded with people in new clothes, eating shumai (also known as shaomai, a type of traditional Chinese dumpling), going to pubs, buying nian hua (New Year Pictures) and watching juggling and other acts. We began to exchange New Year greetings with our friends and relatives on the second day of the New Year.

My father in formal dress went out with his servants to bai nian. After he passed away, my mother asked me to wear formal dress to bai nian, which depressed me a lot. A teenager in formal dress often drew much attention in public. People all looked at me in sarcastic, sympathetic or envious ways. Now I understand why my mother asked me to do this. She hoped that I could achieve a rank of juren in the imperial examination to bring honor to my family, just as my father had done, even though the imperial exam had already been abolished.”

Lao She (1899–1966) was one of the most significant figures of 20th-century Chinese literature. Born and bred in Beijing, his works are known especially for their distinctive Beijing style. In one of his essays, he vividly depicts how the people in old Beijing celebrated the Spring Festival:

“The celebration of Spring Festival often started as early as the beginning of the twelfth lunar month. Laba zhou was the most important food served in households and temples on the eighth day of the month (the day is called laba). This traditional porridge was a mixture of various grains, beans, nuts and dried fruits. Laba garlic was also cooked on this day. Peeled garlic was pickled in vinegar, then sealed until the reunion dinner. About 20 days later, the garlic turned jade-like green and the vinegar slightly spicy. Since the eighth day, stores rushed to stock nian huo (special purchases for the Spring Festival). Many stalls emerged along streets, selling Spring Festival couplets, nian hua, sweetmeats, daffodil blossoms and other objects that were only available in this season. These stalls made the hearts of children beat faster.

In imperial China, schools closed for a month beginning on the 19th day of the 12th lunar month. As kids were scrambling for snacks and toys, adults were on the wing preparing for the festival, purchasing food, making new shoes and clothes for kids, wishing them a refreshing start for the new year.

After the 23rd day, people got much busier. Before New Year’s Eve, the Spring Festival couplets needed to be glued onto the sides of doors and the spring-cleaning had to be finished. Households had stockpiled food for the next week, because most shops would be closed during the festival, only opening on the sixth day of the New Year.

The lunar New Year’s Eve was bustling. Families were in full swing cooking for the reunion dinner. Delicious smells of liquors and meat dishes wafted up from kitchens. Family members in brand new clothes came together. Houses were brilliantly illuminated throughout the night, along with the ceaseless noise of firecrackers. All those who had left their hometowns to make a living returned home to have a reunion dinner with their family members and pay homage to ancestors. Everyone stayed up on this night except young children.

When it came to the first day of the New Year, men came out to bai nian in the morning while women stayed at home to receive visitors. Meanwhile, many temples in and out of Beijing were open to the public.

Large-scale miao hui, or temple fairs, were usually held around the fifth and the sixth day of the Chinese New Year. Children were particularly excited to go to the fairs, where they could enjoy nature outside the city, ride donkeys and buy toys that were only available during Spring Festival.”

edited by REN GUANHONG