Ritual representations in novels open new perspectives

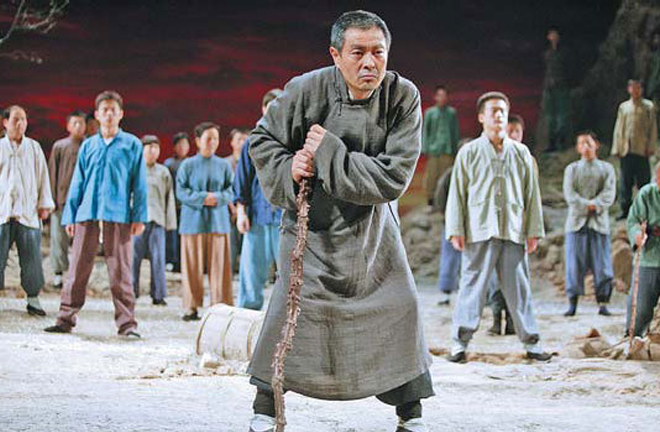

A scene from Beijing People’s Art Theater’s adaptation of White Deer Plain Photo: CHINA DAILY

The need for ritual and ceremony is embedded deep within our DNA, and as such rituals provide a valuable approach for the study of societal evolution. A good ceremony lifts people beyond their ordinary everyday reality. In literary works, rituals can be condensed into specific details and extended into grand narratives. When a novel is examined from the perspective of rituals, representations of ceremonies in the text become not only a mode of storytelling but also a window into culture, history and the text itself. Moreover, the study of rituals widens the reach of literary research.

Multi-faceted rural culture

In rural literature, the representation of rituals serves as an important form of expression. It exposes both the poverty and the wealth of the countryside and both the idealism and the absurdity in rural stories through a specific set of elements, thus revealing both the fracture and the development of rural culture.

In The Book of Life, the author Li Peifu gives a detailed description of the “grand” funeral ceremony of Mr. Chong’s wife, the only name she is given, who does all sorts of “bad things” in her lifetime. The woman struggles to feed her three children because she is the only laborer in the family. When she steals some stalks of corn and some sesame beans, she is labeled a thief. Her children then leave her because of their shame at her stealing. Ultimately, Mr. Chong’s wife dies in loneliness, leaving only a broken fan and a bankbook.

Upon learning the existence of the bankbook, her children come back home in a hurry, so the poor woman is given a “grand” funeral—“A decent banquet, with forty tables in the courtyard, fish and chicken on the plates, quite the funeral feast.” Though helplessness and despair torment Mr. Chong’s wife her whole life, the thirty-thousand-yuan bankbook brings her three children back from far away. Her grand funeral ceremony is the epitome of her life of suffering and enduring, as well as a vivid illustration of the lowness of her children.

In Lu Yao’s The Ordinary World, the description of ceremonies is also intriguing. Tian Wanyou’s one-man rain prayer ceremony is a song of life and survival for his fellow desperate villagers. “The heart sank at the cry of the prayer—the tone of sorrow is indeed the cry of despair from all the peasants!”

However, the sadness does not bring change for the people of Shuangshui Village. Later, when they dig up the upstream dam, the ensuing flood washes away Jin Junbin, who is then celebrated as a “martyr” by the villagers. The solemn rain prayer ceremony and the “state-of-the-art” martyr’s funeral work in correspondence to depict a farce in the barren countryside, but also a real tragedy.

Such rituals are common in other rural literature. For example, in Guan Renshan’s Mai River, there are rituals to worship the land god for the peace of the family. In Yan Geling’s The Ninth Widow, there are also many descriptions of folk rituals in the telling of the legendary life of the main character Wang Putao, such as honoring and punishing the black dragon.

The rituals and ritualistic behaviors upheld by peasants in rural novels have little to do with religion. They are mostly cultural and behavioral patterns derived from traditional ways of thinking, and they serve as unique modes of problem-solving formed out of the accumulation of experience. From these rituals and their narration, we can see the unique countryside lifestyle, along with the farmers’ despair, unwillingness and struggle in face of the fracturing of rural culture.

In response to social change after China’s reform and opening up, a large number of positive literary works about rural society emerged in the 1980s, which contributed a more multi-dimensional and diverse representation of social life as well las many epic tales.

Absurdity vs. idealism

Chen Zhongshi’s White Deer Plain is another typical example of ritual representations. The novel describes the great changes of the White Deer Village over 100 years, including changes to many folk customs, witchcraft, ancient teachings and cruel punishment methods, as well as many absurd and surreal ritual descriptions. Behind the scenes, it shows the confrontation between such ideas as openness and feudalism, morality and decadence, submission and resistance, ancient and radical, and exodus and return.

In White Deer Plain, the main character Bai Jiaxuan’s treatment of his father’s funeral shows a stark clash between old and new culture. Facing the conflict between the traditional imperatives of “three years of mourning for one’s parent” and “there are three things which are unfilial and to have no posterity is the greatest of them,” Bai submitted to the latter. He began to marry again two months after his father’s death. Indeed, Bai spent his life venerating and imitating Confucian scholar Mr. Zhu, and upon having a child, he thought he had honored the ancestors, and thereafter he started to change the customs and exercise power in the vast Guanzhong Plain of Shaanxi Province.

In White Deer Plain, Tian Xiao’e is another outstanding character. Her biggest hope is to be an honest peasant’s wife, but even such a trivial dream is difficult to realize. She is not accepted by the people of the White Deer Plain because her marriage to Heiwa lacked a formal wedding ceremony. She is subjected to many ritual punishments and finally forced to end her life. Even after she dies, she must accept the ritual arrangement, and her ashes are buried under the tower, an act which prevents her from a second life.

The rituals in the novel, such as festivals, the naming of children, funerals and weddings, fill the novel with hallucinatory stories. The absurd atmosphere that is both realistic and fantastic is a true portrayal of the White Deer Plain and also of rural China.

In the face of rapid urbanization, rural society presents unprecedented complexity, including the joint forces of capital, power, systems and other factors. This complexity causes the countryside to constant shift between absurdity and reality.

Similarly, in Zhou Daxin’s Scenery of the Lake and the Mountain, posthumous wedding ceremonies and rituals welcome ghosts and gods. However, bit by bit the absurdity is stamped out by Nuannuan, a youthful villager who has unrelentingly pursued a better life in the city and has been called home to care for her mother. The novel underlines an idealist’s sincere expectation for rural reform and a visionary writer’s poetic dream for a transformed rural society.

Evolution of rural spirit

In Scenery of the Lake and the Mountain, a series of images, such as beautiful mountains, lush woods and the historic Great Wall of the State of Chu, constitute the tranquil Village of King Chu, which seems to have been forgotten by contemporary industrial civilization. In contrast with the simplicity and goodness of the peasants, there exists a distorted and ugly human nature.

Nuannuan is a woman with traditional virtue, beautiful and kind, righteous and polite. When she is called back from Beijing to take care of her sick mother, she encounters a posthumous wedding ceremony, making her realize the backwardness of the countryside in terms of economy and ideas. The event signals a shift in Nuannuan’s life.

Upon her return, Nuannuan forges ahead with plans to invigorate the rural village with new enterprises and business. As the sublime image of a woman in the eyes of the village men, village chief Zhan Shideng plans to marry Nuannuan to his younger brother, but her refusal and subsequent elopement with the desperately poor young man Kuang Kaitian brings on the full wrath of the rampant chief.

Worldly, resilient and spirited, Nuannuan contends with all that transpires around her as she marches on to build her career and life. The novel provides a unique perspective on rural life in China, scratching the surface of the monumental changes brought by modernity and delving into the core structures of a village in the grip of rigid tradition.

Throughout history, ritual and a sense of ritual have always been key ways for humanity to perceive and understand the world, and their deployment in literary works is naturally an important channel for interpretation. Across diverse literary creation and criticism, ritual provides a glimpse into characters and society, and thus the profound connotation and historical significance behind ritual representations requires further study.

Yin Wenwen is from the School of Literature at Heilongjiang University.

edited by YANG XUE