Painted pottery vital to Chinese archaeology

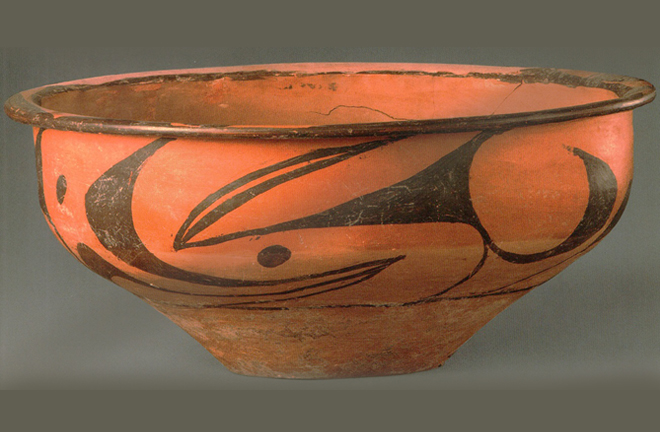

A painted pottery basin with a petal design Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

Painted pottery remains were discovered by Swedish geologist and anthropologist Johan Gunnar Andersson in Yangshao Village, Mianchi County, in central China’s Henan Province, in 1921. It has been nearly one hundred years since the discovery. Highly special to the history of Chinese archaeology, the remains have accompanied the beginning and development of the discipline in China and are significant to prehistoric Chinese culture, even the origins of the Chinese civilization.

Chinese archaeology

The finding of painted pottery remains ushered in the discipline of Chinese Neolithic archaeology. They are the earliest prehistoric cultural remains discovered in China.

Before coming to China, Andersson already enjoyed a global reputation. At the time, the Chinese government invited him to hunt for mining resources like iron ore, while he was also keenly interested in ancient Chinese culture.

During many attempts to search for paleontological fossils and stone artifacts in Henan, he accidentally found the coexistence of stone implements and painted pottery pieces in Yangshao Village, and he was rather confused. Later he learned that similar phenomena existed in the ruins of Anau in Central Asia, so he began to pay close attention to ruins of this kind. In October 1921, he began excavating in Yangshao.

The excavation had a clear academic motive, and Andersson adopted relatively scientific approaches. Most importantly, the remains and knowledge he acquired opened up many topics for Neolithic archaeology in China, running through the whole development course of Chinese archaeology. Therefore, some scholars regard Andersson’s excavation as the beginning of Chinese archaeology.

Stratigraphy

Archaeological stratigraphy is a basic method for obtaining material remains by drawing upon related concepts in geology. According to its theory, ruins consist of different layers of sediment accumulated over time. They are not disordered. By exposing the levels of sediment layer by layer, the relative chronological relationship between remains and relics can be clarified, thereby reconstructing the living scenarios of ancient humanity in different periods.

In the development of stratigraphy, the principle of excavation was shifted from determining chronology strictly based on horizontal strata, known as horizontality, and began to take traces or remains of human activity into account, marking a turning point of modern Chinese archaeology. The turning point started from the dig of Yinxu, known as the source of the archeological discovery of oracle bones in northernmost Henan, which was led by anthropologist and archaeologist Liang Siyong and inseparable from painted ceramics.

Liang pursued undergraduate studies in archaeology and obtained his master’s degree in the US. He was the first overseas Chinese student to major in modern archaeology, or field archaeology. Receiving formal training in modern archaeology, he participated in the excavations of the Indian cultural ruins in western America and the Site of Xiyin Village in Xia County, Shanxi Province. After returning to China in 1930, he presided over the excavation of the Hougang Site in Anyang, Henan, the next year, as he abandoned the principle of horizontality and broke new trail by excavating with the cultural layer as the unit.

In the dig of the Hougang Site, Liang categorized many different natural strata into layers dating to the Shang Culture (c. 1600–1046 BCE), the Longshan Culture (c. 2500–2000 BCE) and the Yangshao Culture (c. 5000–3000 BCE). The method of stratification made it possible to generalize human cultural relics by excluding unrelated phenomena from complex sediment. In this way, seemingly inessential pieces of painted pottery, black pottery and white pottery could be distinguished from chaotic deposits and given humanistic significance.

Typology

Borrowed from morphological taxonomy in biology, typology is the most fundamental methodology in archaeological research for classifying and thus systematizing material remains. Studying the logical sequence of external morphological classification of and changes in archaeological remains can help judge the relative date of the remains, establish the relative chronology of the site, compare types of remains belonging to different cultures and determine the inheritance or interrelationship between cultures to build archaeological cultural genealogies.

In China, typology is usually associated with modern archaeologist Su Bingqi. His studies of li three-legged cauldrons signified the maturing of Chinese typology. After Swedish archaeologist Oscar Montelius generalized the theory of typology, its first systematic application to Chinese archaeological practices started with painted pottery, such as three-legged cauldrons.

Earlier on, Andersson used typological principles to classify pottery, including painted pottery, and did analysis based on their texture, color and pattern. Moreover, he conducted a comparative analysis between painted pottery discovered in Yangshao and ceramics of the Tripolye and Anau cultures, in a bid to prove the hypothesis that Chinese painted pottery was imported from the West.

Li Ji, who is considered the founder of modern Chinese archaeology, also resorted to typology to analyze pottery pieces unearthed from Xiyin Village, including painted pottery, and made a comparison of prehistoric cultures in the village, Yangshao and the northwest part of China.

After completing undergraduate studies, Liang Siyong went back to China and spent one year organizing materials excavated from Xiyin Village. The materials were mostly broken pottery pieces including painted ceramics. As a result, he wrote a paper titled “New Age stone pottery from the prehistoric site at Hsi-yin Tsun, Shansi, China” in English.

In his classification of the pieces, Liang first put together statistics of the two broad categories: unpainted pottery and painted pottery. Then he selected 1,356 painted pottery pieces from more than 10,000 for deeper classification and research. He discovered that 1,349 of these pieces were single-colored pottery, all in black, red or white, and the remaining seven pieces were multi-colored, the color combinations being red and black, and yellow and black. Additionally, he formulated a table to organize these pieces by color and pattern.

Though lacking stratigraphic proof, Liang’s principles of classifying painted pottery from Xiyin Village were so precise that they have been followed even today. The fundamental principle of typology is to admit changes and also rules in the changes. Before Su Bingqi’s li three-legged cauldons, earlier scholars’ examination of Chinese typology through painted ceramics was faltering yet valuable.

Origins of Chinese civilization

Culture and civilization have been much talked-about topics since the emergence of the modern humanities. The exploration of cultural origins concerning China started from the study of painted pottery.

In the 1920s, while saving the nation from subjugation, Chinese nationals were also reflecting on why the country with an ancient civilization of thousands of years was left behind in the world. Was the Chinese culture superior to the Western culture, or vice versa? Issues regarding Chinese and Western cultures were heated topics at the time.

In the field of archaeology, Andersson was the first to comment on such issues. By comparing painted pottery unearthed from Yangshao Village in China and from Central Asia, he solicited opinions from Western archaeologists and put forward the hypothesis that the Chinese culture originated from the West.

Regarding painted pottery as a highlight of Chinese prehistoric culture, he argued that Western advanced agriculture as embodied in painted pottery was introduced to China in the Neolithic age and became part of Chinese prehistoric culture. With the material support of painted pottery, in addition to the distinguished status of Andersson in academia, the theory was quite popular back then.

However, Chinese scholars held a prudent attitude toward the view. Academically speaking, it was not convincing to conclude that ancient Chinese culture was imported from the West simply through a comparison of patterns on Chinese and foreign painted ceramics. From the perspective of national sentiment, the statement that the time-honored Chinese culture stemmed from the West was also unacceptable.

Nonetheless, there was indeed a missing link between remains found by Andersson in Yangshao and those dating to the Shang Dynasty discovered in Anyang. In order to prove their respective views, Andersson went to the West to seek the path of the spread of painted pottery, while Chinese scholars traced the source of the Shang civilization within China.

Against this background, the Longshan Culture was discovered. The discovery caused a sensation in Chinese academia, because it was widely different from the already-known Yangshao Culture and the pottery craft found there was obviously more advanced than black pottery and oracle bones. This indicated a close relationship with the Shang Culture that the Yangshao Culture couldn’t match.

However, the existing academic framework and ongoing warfare made it impossible to carry out extensive field research, so the relationship between the Yangshao and Longshan cultures was not correctly understood despite the stratigraphic overlying of the two.

After 1949, along with massive infrastructure construction, a great many archaeological sites were unveiled. In Shan County in Henan, a place close to Yangshao Village, the Miaodigou II Culture (c. 2900–2800 BCE) was found. Pottery of the culture was mostly handmade like that of the Yangshao Culture, instead of being made using the potter’s wheel as typical in the Longshan Culture. A number of painted ceramic vessels unearthed suggested the Miaodigou II Culture’s close relationship with the Yangshao Culture. Meanwhile, pottery pieces resembling eggshells appeared in abundance. The emergence of pottery such as jia drinking vessels, ding cookware and dou utensils for meat eating demonstrated a prelude to the typical pottery made during the Longshan Culture period. The whole Miaodigou II Culture showed salient transitional features.

More importantly, a layer indicating the sequential development of the Yangshao, Miaodigou II and Longshan cultures was revealed, attesting to continuous cultural traditions started from ancient times and passed down from the Yangshao Culture to the Longshan Culture and then to the Yin and Zhou dynasties in the Central Plains. The theory that the Central Plains was the center of the Chinese civilization thus came into being.

As large quantities of archaeological remains were unearthed across the nation, many other theories were brought forth successively. In recent years, some scholars studied the Miaodigou Age (c. 4005–2780 BCE) and proposed that a cultural community consisting of three regions during the period raised the curtain of early Chinese civilization. Analysis of painted pottery excavated from the three areas was an important part of the recent studies.

Even to this day, explorations have continued to deepen on unique implications of painted pottery remains and the significant role they played in the origination of Chinese culture and civilization.

Zhu Yanzhen is a doctoral candidate from the Department of Archaeology at Renmin University of China.

edited by CHEN MIRONG