Paintings mirror new China’s growth

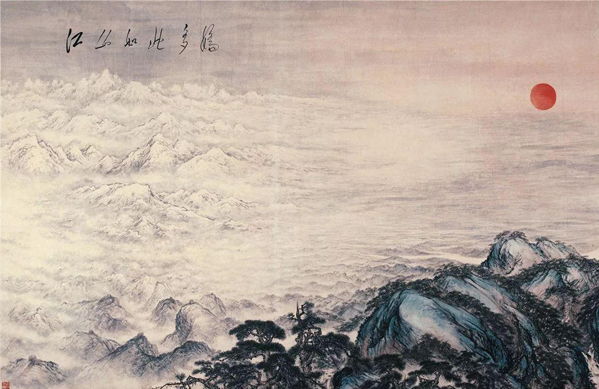

“The Land is So Rich in Beauty” (1959) by Fu Baoshi and Guan Shanyue, inspired by one of Mao Zedong’s poems. Photo: FILE

In the past 70 years since the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the development of Chinese art has typically mirrored and corresponded with social change. As a representative of the native arts, Chinese painting has gradually entered modernity.

Early reformation

Beginning with the founding of the PRC, the reformation of traditional Chinese painting was conducted in sync with social transformation. In the early years of the PRC, artists were encouraged to employ realism to highlight the political significance of art paintings, thus causing a boom in painting and new trends of thought. Trends of that period harked back to a schism in the arts with beginning in the New Cultural Movement in China between 1917 and 1921. The schism developed between artists seeking to preserve their heritage in the face of rapid Westernization by following earlier precedents and those who advocated the reform of Chinese art through the adoption of foreign media and techniques.

In April 1949, a debate about traditional Chinese paintings was conducted by People’s Daily. In the same month, an exhibition of new Chinese paintings was held in Zhongshan Park in Beijing, displaying the reform of traditional painting made by over 80 artists from Beijing. After that, Fu Baoshi (1904–65), a leading artist of the New Chinese Painting Movement, began to explore the style inspired by Chairman Mao Zedong’s poetry, thereby revolutionizing the tradition of Chinese landscapes with his innovative brushwork and unique composition.

During the 1950s and 1960s, artists were divided into “Northern” and “Southern” schools. The Northern school was represented by artists from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, such as Lu Chen, Yao Youduo and Zhou Sicong. The leading figures of the Southern Group were from the Zhejiang Academy of Art (it was renamed China Academy of Art in 1993) in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. Both branches were dominated by the school of realism. However, the painters of the Northern school worked on the basis of sketch art, applying sketch techniques in Chinese paintings to create a precise, detailed and accurate representation. Artists from the Southern school preferred to maintain the tradition of literati painting (literati painters were known as sensitive poets and scholars who were also gentlemen painters; they painted intuitively without conscious thought of function or beauty), which distinguished their artworks from those of the West. At the very center of this scholarly ideal was the art of calligraphy, which abstractly expressed the real nature of the individual who wielded the brush, without interposing any pictorial description.

Reform and opening up

When it came to the 1980s, the reform and opening up encouraged Chinese artists of the time to explore further. Comparisons of the cultures of the West and the East, and the deep reflection of the nation’s history became the main focus of the Chinese artists. This consciousness was further promoted in the early 1990s.

The sixth national fine arts exhibition held between 1984 and 1985 was regarded as a milestone in the history of Chinese contemporary fine arts. The public of the time found the paintings from this exhibition quite different from those of previous exhibitions. Increased simplicity was exhibited in the paintings from this exhibition, such as “A Miner’s Wife” by Tang Yongli, which used a large amount of grey and black. The techniques and methods employed tended to be more diverse. For instance, the figures in the “Forest of Stone Tablets” by Tian Liming were painted like white sculptures. Some artworks also showed the efforts of innovation or trying to do “what was disapproved of by the orthodoxy,” such as the parallel lines employed in the composition of “Fishermen’s Song” by Xu Wenhou. These artworks represented the young and middle-aged Chinese artists’ advances in the arts.

Since the mid-1990s, China has experienced rapid economic growth. In this context, the whole society has looked forward to a new type of position and form of self-identity. In the art circles of the time, picking up the traditional culture, extracting and using its essence in the modern arts became the key point of leading the way of Chinese fine arts into the future. During the last ten years of the 20th century, the whole cultural circle in China was dominated by the ideas of inheriting and studying traditional culture.

During this period, the most distinctive trend in the domestic art circles was the diversification of ink wash painting, featuring more themes and techniques than ever. Many artworks appeared with more Western elements. Some accomplished old artists caught the public attention again with their outstanding new works. Young and middle-aged artists began to change old ways of thinking and rethink the issues of the traditional and the modern, the East and the West.

New era

Coming to the 21st century, Chinese artists face the challenges of presenting Chinese painting to the world. With more exposure to Western culture, a large amount of Western arts and techniques has been introduced into China and been widely adopted in Chinese art circles. Meanwhile, as an emerging economy, China is eager to be culturally recognized in the world, and the Chinese arts are expected to be more influential in cultural exchanges with other countries.

In the new era, more and more Chinese artists and scholars have realized the significance of preserving traditional elements when innovating with and diversifying Chinese painting. These traditions include those formed in recent history and represented by Wu Changshuo, Qi Baishi, Huang Binghong and Pan Tianshou, and those developed by the “Four Wangs” (including Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Wang Hui and Wang Yuanqi, who represented the so-called “orthodox school” of painting; it was “orthodox” in the Confucian sense of continuing traditional modes) and the “Four Monks” (including Zhu Da, Shi Tao, Hong Ren and Kun Can, a group of monks portraying the complicated state of their inner world in their unique styles that differ from the old traditional patterns of the Four Wangs) since the Ming and Qing dynasties. The traditions established by the non-official painters and the idea of dividing Chinese painting into “Northern” and “Southern” schools set forward by Dong Qichang (1555–1636; the one who maintained that the Southern school emphasized a sudden, intuitive realization of truth, whereas the Northern school taught a more gradual acquisition of such insight) are also involved in the traditional elements that should be preserved.

The article was edited and translated from Chinese Art News. Yu Yang is the director of the Department of Chinese Painting Study at the Central Academy of Fine Arts.

edited by REN GUANHONG