‘Salons’ of intellectuals in ancient China

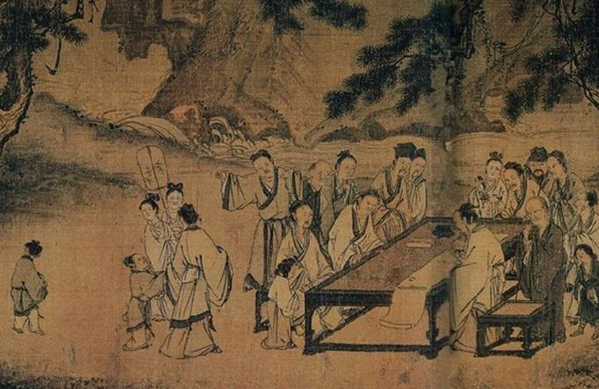

A detail from “Elegant Gathering in The West Garden” by the Song artist Ma Yuan Photo: FILE

Yaji (literally, elegant gathering), refers to a gathering of intellectuals in ancient China, held to amuse the participants, refine the taste and increase the knowledge of the participants through conversation and recreation. The Orchid Pavilion Gathering (also known as the Lanting Gathering) and the gathering of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove are famous gatherings that have echoed throughout the ages. The participants of these gatherings may not have known that their gatherings would eventually become important events in literature and the arts. Records and artistic works related to these gatherings have inspired generations till now.

Poems and drinking

Before the ancient literati held parties spontaneously, gatherings aiming at poetry recitals and other artistic practices were hosted by emperors or nobles. During the Jian’an Period (the 196–220 period during the reign of the Emperor Xian of Han), stimulated by the literary achievements of Cao Cao and his sons, Cao Pi and Cao Zhi, a literary circle was formed, represented by the Seven Scholars of Jian’an, a group of representative literati at that time. Their contacts are considered as the earliest form of yaji. In a letter to his friend Wu Zhi, Cao Pi recalled the gatherings they participated in—“We used to hang out together. Our carriages were next to each other when we were out; our seats were next to each other when we sat down for a break. When we toasted each other, musicians started to play stringed and wind instruments. With our faces flushing and ears hot [because of the alcohol], we raised our heads to compose poems. When indulging ourselves in those gatherings, we didn’t realize that those moments were so precious.” These words epitomize Cao’s friendship with the seven scholars of his time as well as the spirit of the joyful gatherings. Drinking and poems were the most important part of these gatherings.

When it came to the Wei and Jin periods (220–420), the literati highly valued an unrestrained and artistic lifestyle, which placed freedom of self-expression above all other desires. Getting drunk became common in their lives. At that time, drinking and literature were developed into an inspiring combination, which became a regular game in gatherings.

It was the famous Orchid Pavilion Gathering that elevated intellectual gatherings and allowed them to become widespread. According to the “Lanting Jixu” (“Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion”) by the great calligrapher Wang Xizhi (c. 303–361), in the beginning of late spring, celebrities and literati of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420) gathered at the Orchid Pavilion to symbolically dispel bad luck and pray for good fortune. A clear winding brook engirdled the gathering, serving the guests by allowing them to float their wine glasses on the water to drink from. One had to drink three glasses of wine if the floating wine glasses arrived in front of him. Elegance became a key word in these gatherings. Participants composed poems when facing the great mountains and lofty peaks, and took the floating wine glasses when seated by a bank or brook. Wang Xizhi highlighted the scenic beauty of the area where the Orchid Pavilion was located. It reflected the literati’s preference for natural beauty at that time.

Qin and tea

“Elegant Gathering in The West Garden,” a painting by Li Gonglin (1049–1106), one of the most lavishly praised painters in a circle of scholar-officials during the Northern Song period, depicted a gathering of literati and artists in the residence of one of the emperor’s sons-in-law. The participants included the great poet Su Shi, Qin Guan, the well-known artists Huang Tingjian, Mi Fu and Cai Xiang, and Li himself. Compared with the yaji depicted in the “Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion,” this painting reveals some new features of the yaji during the Song Dynasty—more diverse and loosely-organized. In this painting, some participants are practicing calligraphy, some playing musical instruments, while others are sitting in meditation. Influenced by the general admiration for reclusion, Taoism and elegance during the Song Dynasty, the yaji was held in a more graceful manner. Since the Song Dynasty, stringed and wind instruments had been replaced by the qin (fretless Chinese board zither with seven strings) in the literati paintings, and toasts when drinking were replaced by the Zen-style of tea art. Qin and tea became the dominant elements of the Song gatherings. Being for centuries the favored instrument of the elite class, the qin is rich with literary connotations and with symbolism. The peaceful and placid sounds it produced represented elegance. It is often seen in literati paintings with sages representing unspeakably subtle aesthetics.

Since the publication of the The Classic of Tea, the first known monograph on tea in the world by the Tang writer Lu Yu (733–804), brewing and drinking tea had become a drinking art supported by systematic theories. During the Song Dynasty, drinking tea was still treasured as a symbol of high culture by intellectuals and the elite class. Different from the method of jiancha (cooking tea) of the Tang Dynasty, the way of tea drinking in the Song Dynasty was called diancha, and involved pouring water on tea powders to make a puree, then adding water to the puree again and whipping the mixture with a chaxian (a bamboo whisk) to create an impressive milky froth. Corresponding to the strict requirements of the method of diancha, the trend of doucha (tea contest) appeared in the Song Dynasty. There were certain standards to judge if the contestants succeeded or not in the contests. One standard was that the appearance of the tea should be freshly white. The other was that the tanghua (the foaming surface of the tea) around the inner wall of the cup should stick firmly to the wall of the container and remain in this state for a while. It was called yaozhan (literally, biting the cup). If the tanghua vanished quickly and thus revealed a trace of water, the competitor would be considered a loser. Doucha was also a popular game in the yaji at that time.

Flowers and incense

During the Song Dynasty, the Four Arts of Life—tea brewing, flower arranging, painting appreciation and incense burning—were regarded as fashionable pastimes.

As an art form, flower arrangement began when Buddhism spread into China, bringing its custom of offering flowers at temple altars. By the Five Dynasties (907–960), this Buddhist custom had been made a popular decorative art form. Boosted by the advanced ceramics in the Song era, vases were more finely made. The Song literati highly valued the pure, clean, sparse and unadorned style of flower arrangement. Flowers and leaves were often endowed with personalities and were selected based on their symbolic meanings. The art of flower arrangement brought the gatherings of literati from usually being staged outdoors to being staged indoors, becoming an inspiring pastime in the yaji.

China has a long history of burning incense. Among the unearthed devices for burning incense, there are a remarkable number of devices that date back to the Warring States Period and the Han Dynasty. Ever since the Song Dynasty, the Chinese developed a sophisticated art form of incense burning, like with tea and calligraphy. Most of the incense used in the Song era was hexiang, made from diverse ingredients, thus creating various subtle scents. Of all the incense ingredients some of the most commonly used include agilawood, sandalwood and cloves. Many renowned intellectuals were also experts at making incense, such as Su Shi and Huang Tingjian. Incense powder was formed into the final product and put into use through various complicated steps, each step adding to the artistic value of this practice. Burning incense brought a sense of romance to the yaji, driving these gatherings to develop in a more detailed and exquisite way, and the ancient literati indulged in a more subtle spiritual world.

Although the yaji continued to change over time, “ya” or elegance as the core value of the gatherings never changed. The ancient literati sought the essence and taste of life in these gatherings.

The article was edited and translated from Wenhui Daily.

edited by REN GUANHONG