Exploring history of Chinese literature

History of Chinese Literature

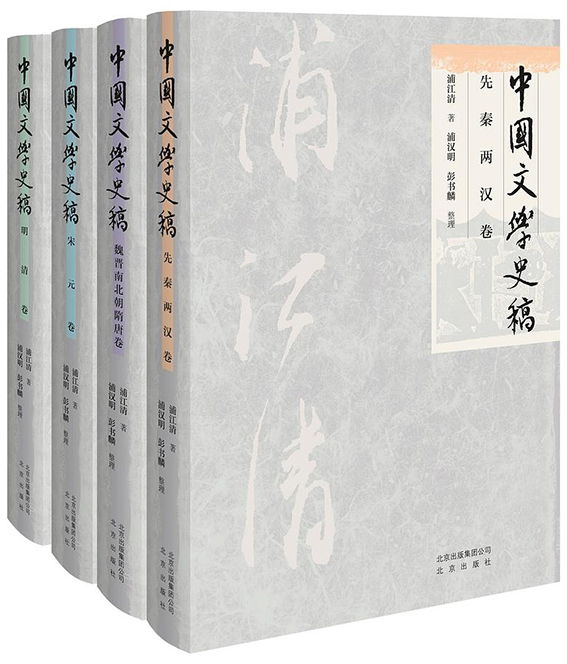

Pu Jiangqing (1904–57) was a famous expert in classical literature during the first half of the 20th century in China. His History of Chinese Literature, compiled by his daughter Pu Hanming and another editor Peng Shulin, mainly introduces the generation and development of Chinese literature, categorized by dynasties.

It is worth noting that in this book, the author discusses the similarities and differences between Chinese and Western literature and their developmental histories based on preserved texts of the early period. He takes the Book of Changes and Book of Documents as the opening of Chinese literature and puts forward the idea that “poetry comes first in Western history while prose comes first in China.”

During his time, most scholars took ballads as the opening of Chinese literature. In the first chapter, he talks about the so-called early songs such as Song of Qingyun, but he points out with prudence that these songs were forged in the books of future generations. At the same time, he also argues that “The Book of Songs is not the beginning of Chinese literature. That’s because according to this Western standard of division, literature had already appeared even before the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), namely, the inscriptions.” Faced with the fact that early Chinese literature was preserved within inscriptions on bones, tortoise shells and bronze objects, the author chooses to be loyal to the literature’s materials. In this way, he tries to discuss the differences in the early forms of Chinese and Western literature and explain the internal causes of these differences.

The author’s detailed analysis of the works such as The Songs of Chu and Dream of the Red Chamber provide an easy way for readers to access Chinese literary history. The author has a unique literary vision. For example, he believes that the most valuable prose in the Book of Documents was “Succession”; when talking about long narrative poems such as The Peacock Flies to the Southeast, he argues that this kind of narrative poem was influenced by the novel. When discussing the relationship between the Monkey King and Hanuman (a mythological figure of Hinduism), he carefully compares the similarities and differences between the two famous characters. He argues that the image of the Monkey King in Journey to the West may be influenced externally, but it is groundless to say that the Monkey King is born out of Hanuman.

Although History of Chinese Literature projects strong personal opinions, it also tries to provide readers with more academic perspectives. For example, when Pu elaborates on The Nineteen Ancient Poems as folk literature, he also calls attention to the different viewpoints of scholars such as Gu Zhi and You Guoen.

edited by YANG LANLAN