Oriental aesthetics calls for cross-cultural studies

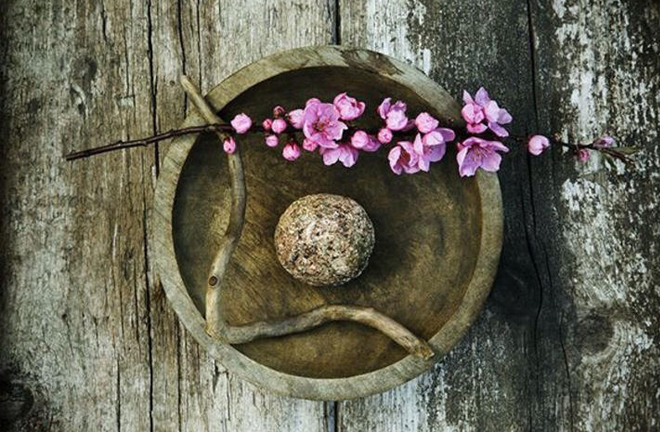

The picture represents a wabi-sabi (transience and imperfection) style in Japanese aesthetics, in which sakura and the other objects reflect wabi (stark beauty), and the background sabi (aging). Photo: FILE

Classic Oriental aesthetics and Oriental literary and artistic thought are a treasure trove of ideas, theories and heritage. Natya Shastra, a theoretical treatise on ancient Indian dramaturgy and histrionics written by the “father of Sanskrit literary theory and criticism” Bharata Muni, is comparable to ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle’s Poetics. The ancient ideals of Japanese aesthetics, including wabi (transient and stark beauty), sabi (the beauty of natural patina and aging) and yugen (profound grace and subtlety), echo the sentiments and temperamental tastes specified in the Sanskrit rasa (essence or taste) poetics of India.

With the unprecedented globalization of the contemporary era, the overlapping and interpenetration between Eastern and Western literary and artistic thought and among the aesthetics of Oriental countries themselves has constituted a significant problem area, calling for the exchange and clash of different literary and artistic ideas from cross-cultural perspectives.

Oriental aesthetics in China

The academic history of Oriental aesthetics in China consists of two parts. The first part is the overall study of Oriental aesthetics and literary and artistic thought. In the 1990s, a wave of Oriental studies swept China. The China Association of Oriental Culture Studies was founded, symposiums on Oriental aesthetics were held, and many publishing houses raced to produce collected translations, works and periodicals on Oriental studies.

For example, Renmin University of China published a collection of translations concerning Oriental aesthetics, including Oriental Aesthetics by American philosopher of art Thomas Munro, Japanese philosopher Tomonobu Imamichi’s Philosophy in the East and in the West and Aesthetics in the Orient, and Aesthetics in the Middle and Near East by Soviet philosopher Mikhail Ovsyannikov.

Chinese scholars also composed works to reflect the full picture of Oriental aesthetics and literary and artistic thought, such as Anthology of Oriental Literary Theories by Cao Shunqing, a professor from the College of Literature and Journalism at Sichuan University; History of Oriental Aesthetics by Qiu Zihua, a professor from the School of Chinese Language and Literature at Central China Normal University; and Oriental Aesthetics by Peng Xiuyin, a chair professor from South-Central University for Nationalities.

They offered overviews of literary theories and aesthetics in major countries and regions in the Orient, such as Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, India and Japan, attending to and analyzing such issues as “the other in Oriental aesthetics” and “Oriental aesthetics in the globalization era.”

The second part of the history of Oriental aesthetics in China is country-specific. Chinese scholars’ research topics concentrate mainly on India, Japan and Arabia, hubs for Oriental aesthetic research.

Significant research has been produced on Indian poetics and aesthetics. Representative works include Selected Works of Ancient Indian Literary and Artistic Theories compiled by renowned Chinese expert on Sanskrit and Indian culture Jin Kemu; Indian Classic Poetics and Integration of Oriental Cultures: A Collection of Sanskrit Poetics Treatises by Huang Baosheng, former director of the Institute of Foreign Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences; and Indian Rasa Poetics by Ni Peigeng, a famous scholar on Indian literature.

Expert on Japanese literature Lü Yuanming’s History of Japanese Literature elaborated on the ten ideals of Japanese aesthetics, while the History of Japanese Literary Trends authored by late professor of Japanese literature and culture Ye Weiqu incorporated theories on history, giving a detailed description of the correlated domain between Japanese aesthetic culture and literature.

Chinese translations of country-specific aesthetics include Japanese Classical Aesthetics composed by Yasuda Takeshi and Michitaro Tada, Pudma Sudhi’s Aesthetic Theories of India, and The Style of Islamic Art by Muhammad Koteb from Egypt.

The aforementioned works remain major references for Chinese scholars in the study of Oriental aesthetics and literary and artistic thought. Crossing the boundaries of country, language and culture, these works represent China’s academic efforts to engage and exchange ideas with other countries or regions in the Orient, and they are important examples encouraging Chinese Oriental aesthetics to adapt to contemporary conditions and go global.

Attention from the West

Oriental aesthetics entered the view of Chinese scholars through Chinese-language documents. It was also brought into the international spotlight through foreign language literature, particularly English.

As some Western scholars pay increasing attention to distinguished academics, important areas and key concepts in Oriental aesthetics, a shift toward Oriental intellectual resources has appeared in the contemporary Western literary theory community.

In the early 21st century, Haun Saussy, a professor from the University of Chicago and former president of the American Comparative Literature Association, titled his report to the association “Comparative Literature in an Age of Globalization,” in which he proposed going beyond the European and Western horizon and examining intellectual resources concerning Oriental literature and aesthetics.

In their masterwork A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Mille Plateaux), reputed French philosopher Gilles Deleuze and French psychoanalyst Félix Guattari shed light on Chinese-born French academician Francois Cheng’s Chinese Poetic Writing and spoke highly of the “lines” in Chinese poems and paintings as well as of the rhythmic beauty of Japanese sumo wrestling.

Enlightened by the “Six Principles of Chinese Painting” proposed by Xie He, a famed art theorist from the Qi state of the Southern Dynasties (420–589), Deleuze created “respiration space” and “skeleton space,” blending ancient Chinese painting theory and European postmodern spatial aesthetics.

In addition, The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, which enjoys a high reputation among Western literary theorists, kept track of such contemporary aestheticians from the Orient as C. D. Narasimhaiah from India, Kojin Karatani from Japan, Li Zehou from China, and Arab scholar Ali Ahmad Said Esber by the pen name Adunis, along with their key theories and concepts.

Nonetheless, the interest in adapting Oriental aesthetics to contemporary conditions and internationalizing it remains weak, calling for more references to and translations of English frontier research to stimulate more in-depth discussion.

Promoting Oriental aesthetics studies

Currently, most significant research findings by Chinese scholars are based on the languages of Oriental countries, such as Japanese and Sanskrit. There is evident estrangement and contrast between domestic and foreign scholars on Oriental aesthetic studies.

To overcome the problem, it is vital to focus on the distinguished scholars, important areas and key concepts in Oriental aesthetics that have entered the contemporary global vision, particularly the vision of the US, Great Britain and China, alongside Chinese and English literature.

Distinguished scholars include, but are not limited to, Japanese scholars Kojin Karatani, Tomonobu Imamichi, Sasaki Ken-ichi and Kakuzo Okakura; Indian scholars Bhrata Muni, Sudraka, Kalidasa, Tagore and Narasimhaiah; and Middle and Near East scholars Adunis, Ibn Rushd, Ibn Khaldun and Abu Hayyan al-Tawhidi.

Examples of important areas are the Eastern harmonious beauty and the Western sublime beauty; Chinese and Indian wei and rasa taste aesthetics and Western catharsis aesthetics; the personification in Indian aesthetics and the cyclical theory in Western archetypal criticism; and impermanence in Japanese aesthetics and ambiguity in contemporary Western aesthetics.

Study of key concepts, or keywords, in Oriental aesthetics is equally crucial. Keywords are concentrated expressions of major issues in a discipline. It is necessary to screen for key concepts with high frequency, striking features, rich connotations and rich Oriental aesthetic characteristics, based on Chinese and foreign research and intellectual resources on the subject.

In Indian aesthetics, central words or concepts include rasa, Natya Shastra, alankara (ornament, decoration) and vakrokti (slant speech). Wabi-sabi, mono no aware (the pathos of things) and yugen are keywords derived from basic areas of Japanese aesthetics. In the Middle and Near East, aesthetic keywords are represented by khvarenah (glory or splendor) put forward by ancient Iranian ethical philosopher Zoroaster and al-thabit wal-mutahawwil (the stable and the changeable) by Adunis; and Chinese aesthetics features such important concepts as yinxiu (hidden excellences), fenggu (vigor of style), shensi (spiritual thought) and yijing (artistic conception).

To adapt Oriental aesthetics to contemporary conditions and make it international is necessary for advancing Chinese Oriental studies in the new era. It can help rectify the imbalance between Eastern and Western aesthetic studies, enrich the theoretical implications of Oriental aesthetic research in China, and contribute to communication among world civilizations and the construction of the Belt and Road initiative.

Cross-cultural aesthetic studies of this kind aim to remove cultural barriers, rationalize the exchange of philosophical and aesthetic thought, shed the shackles of the traditional dualistic approach, and seek a new type of aesthetic vision to serve the community with a shared future for mankind, thereby building better contemporary global aesthetics.

Mai Yongxiong is a professor from the College of Chinese Language and Literature at Guangxi Normal University.

(edited by CHEN MIRONG)