Private writing provides supplement to public narratives

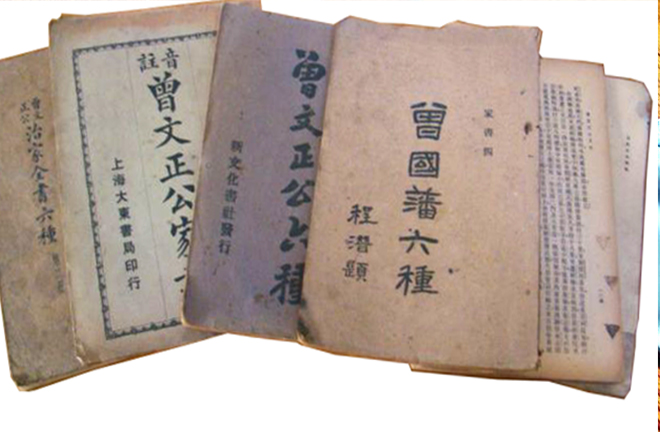

Zeng Guofan, a very important official in the late Qing Dynasty, and the founder and leader of the Xiang Army, made diary writing a habit of his life. These diaries are a window into the inner world of Zeng, providing insight into an influential figure’s personality and psychology and the history of 19th century China. Photo: FILE

By definition, a diary is a record with sequential entries arranged by date reporting on personal experiences, thoughts and feelings, and its stylistic function is the same as that of other writings, which is as a narrative-based text. Due to its highly personal nature, a diary is often juxtaposed with letters, memoirs and biographies, collectively referred to as private documents or personal records, with the typical characteristics of private writing and non-public communication.

However, as an important carrier of social memory, any personal narration inevitably has the traces of a social text. Diaries also have another side that responds to the structural social forces and historical processes encountered by specific groups of people, and they have a public narrative attribute due to their rich details of historical processes, social changes and public events.

In fact, under the historical tradition of “every family and state has its own history,” the initial form of diary writing in ancient China is quite different from that of later generations. It is often modeled on an official calendar, so its literary attributes and personal writing style are not obvious.

Nevertheless, given the difference of each writer’s identity, stance, motivation, narrative techniques and content, diaries appear to be diverse and distinctive, therefore many types of diary research exist.

Theoretical paradigm

We can roughly group the theoretical paradigms of Chinese diary research into the following three categories:

The first is the historical textual research paradigm, which focuses on the textual research of diary text, diary writing and historical facts, and it is often used as a cross-reference with other historical materials.

Based on the constructed nature of history and social reality, researchers not only focus on differentiated micro-historical processes under the influence of a grand history, but also focus on the analysis of the participation and construction of individuals or groups in the historical process. Since the 1950s, especially after the 1970s, under the influence of new historicism, researchers have turned from the macroscopic perspective to the microscopic one, from uncovering the laws of history to describing the logic and significance of daily life. Accordingly, historical records and interpretations based on official texts have been deconstructed, and the exclusive orthodox view of history has been challenged in China, while the social and life histories that are closer to the masses have been increasingly valued.

Naturally, the second category is the social history and life history paradigm under new historicism, focusing on the close relationship between the lives of those recorded in a diary and the grand history, national institutions and specific organizations, highlighting the constructed nature of those recorded.

In this aspect, researchers can probe into individuals’ thinking on and understanding of social changes and national institutions from the perspective of meaning interpretation, and they can also examine the emotions, attitudes and other social-psychological states of individuals and families within the historical process.

The third category is the paradigm of action research. The main goal of researchers is not textual research or analysis of diary data, but to take diary writing and analysis as an important means of individual reflection, self-adjustment and even external intervention, with obvious therapeutic or developmental orientation.

That said, researchers who conduct action research often delve into the impact of social and cultural factors, especially the state system and cultural traditions, on diary writing preservation and dissemination.

Two sides of the coin

At present, with the popularization of microblogs and WeChat Moments, the form and content of diaries vary greatly, so the data collection and analysis methods available to researchers are also more diverse, and not just limited to qualitative research.

Though the diary has a variety of carriers, forms and content, on the whole, it highlights privacy, continuity, details and personal reflection, which is typical of private writing. At the same time, the unique value of diary literature is closely related to its vivid and detailed description of the grand historical process and social systems, and its basic value as a type of research material is to promote the understanding of the human community and the whole society, rather than presenting the variety of daily life and individual history itself.

Therefore, the central issue is to reveal the public narrative dimension from personal recordings and then to discuss the relationship between individual experience and grand historical process, which presents both opportunities and constraints for diary research.

On the one hand, the diary can be regarded as the “most authentic and delicate” personal writing form. With rich individualized perceptions, emotional interventions and meaning interpretations, the diary can vividly depict the recorder’s daily life and life journey.

On the other hand, the diary also holds a public narrative dimension that transcends private speech. It can offer a glimpse into the social and cultural norms behind it. That is to say, private writing and public narrative are both sides of the diary, making it a unique research material.

Obviously, diary research does not only correspond to research topics like psychological history, individual life journeys, and individual responses within macro historical processes. It also displays some unique qualities in its theoretical perspective and research methods.

Similar to that in South Korea, Japan and other east Asian countries, Chinese diary research’s unique qualities and significant aspects differ from those of diary research in Europe and the United States. This is why researchers at home and abroad have put more stress on the collection, collation and analysis of diary data in recent years.

Moreover, the identification of the value of Chinese diary research prompts us to dig deeply into the abundant diary data, and it also helps us further clarify the agenda, theoretical perspectives and methods of domestic diary research, which will provide answers and clarification to specific social studies.

Due to the dramatic transformation of the Chinese society, in addition to the overlapping of traditional agricultural society, modern industrial society and postmodern society, Chinese society has prominent modernity issues, including compressed modernity. In this light, diary study has irreplaceable value in terms of its providing the analyses, mentalities and responses of different people in this situation.

Constraints

However, compared with the rapid development of oral history research, diary study still relatively lags behind, and it faces many constraints.

First, diaries that are retained and collected as historical documents or research materials are relatively limited, and few research institutions specialize in diary data collection and analysis, so we need to step up our efforts in diary data collecting, organizing and sharing, to fully explore its value.

Second, the current diary literature includes more second-hand and elite diaries, but much fewer diaries from ordinary people. Meanwhile, researchers tend to give priority to diaries that are of literary or historical importance, which leads to limitations on research objects and topic selection, not to mention that speculation on the views and lives of ordinary people become based only on those of the elite class, rather than factual recordings.

Third, as secondary data that are not directly collected by researchers, the objectivity and usage of diaries need to be carefully screened, and they must rely on corroborating and integrating studies with other sources. However, this is often not the case in many diary studies.

Going forward, to promote China’s diary study, in addition to further clarifying the nature of diary data, existing documents and their time and location, and the number and distribution of diary recorders, we need to strengthen the systematic collection of diaries and focus on the constructive effects of national institutions, local social cultures and individual socioeconomic statuses on diary writing forms and content.

At the same time, researchers need to treat the objectivity and reliability of diary literature with caution and avoid using personal history narratives to replace grand historical or social change, paying attention to research strategies such as extending the case study to carry out an integrated diary study.

In addition, the rise of social media and online communities has vastly increased connectivity between individuals and changed the scope of diary writing motivations and communication, on which basis personal diaries further move from being a private matter to a means of public communication, to some degree eliminating the inherent tension between private writing and public narrative. Therefore, we also need to investigate new diary forms such as online blogs and the transformation of the exclusive, personal expression of elites to a massive, popular and interactive expression.

Wang Xuhui is from the School of Ethnology and Sociology at Minzu University of China. Li Xianzhi is from the School of Culture and Communication at the Capital University of Economics and Business.

edited by YANG XUE