Shikumen home to old Shanghai life

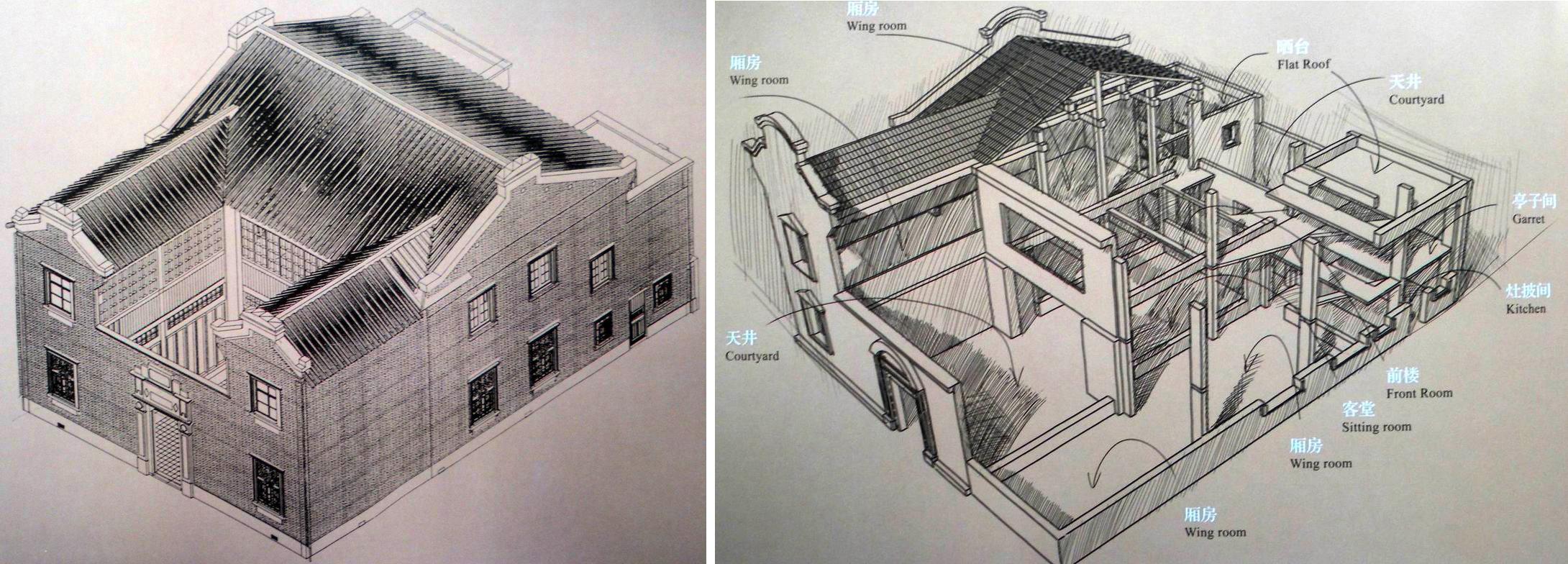

Building elements of a typical shikumen house Photo: SHANGHAI SHIKUMEN

Commissioned during the urbanization of Shanghai, shikumen have sheltered Shanghainese for ages. The first shikumen appeared in the 1850s, designed as a type of efficient structure with a smaller site area, easily constructed with fewer materials, and a lower cost. A typical shikumen consists of three rooms upstairs and three rooms downstairs. At the center of the downstairs area is the sitting room flanked by wings (xiang fang) on the left and right, and the layout upstairs is the same. Later, smaller-sized shikumen emerged, including one with two rooms upstairs and two rooms downstairs, or even with a single room upstairs and a single room downstairs. The main door of a shikumen is made of heavy wood, painted glossy black, adorned with granite or other stone lintels, thus giving rise to the name “shikumen” (shi refers to stone). As time moved on, a new type of shikumen emerged to provide better accommodation for wealthy middle-class families. The tall walls and black main doors were removed, and instead modern sanitary equipment and gas burners were included, and the courtyard was transformed into a little parterre area. This new type of shikumen was called the “reformed style” of shikumen.

Because of the high rent costs, a shikumen house was often occupied by six or seven families, sometimes even more than a dozen families. The entire spectrum of Shanghai life took place among these residents—people of all walks of life, sharing different lifestyles and interests. The famous play “Shanghai Wuyan Xia,” or “Under Shanghai Eaves” (1937) by Xia Yan (1900–1995) vividly portrayed the tenement life of ordinary people living in a shikumen house during the 1930s.

An article by a teacher, “Gelou Shijing” or “Ten Scenes in An Attic,” depicts the lives of ten families in a shikumen building. The front hall was occupied by a policeman with his wife and two teenage girls. The policeman was a loan shark, offering loans to poor vendors nearby. In the back hall lived a family of five—a couple and their three kids—and the parents taught at a primary school within the same complex. The “second landlord” (people who sub-let some of the rooms to rent the whole house) in his fifties and his wife in her twenties lived in the kitchen behind the back hall. The “second landlord” went to enjoy pingtan (a regional variety of the musical or oral performance art popular in southern China) in performing halls every day, leaving all the housework to his wife. Two dancing girls lived in the bedroom on the second floor. They usually went to work in the afternoon or evening, and came back after midnight or at dawn.

In order to get more rent, it was common for the owner of a shikumen house to create one or two rooms by adding a floor slab between the two floors. The room built in this way between the first floor and the second floor was called an er ceng ge, and the one between the second floor and the third floor or the roof was called san ceng ge. In this article, a cobbler and his wife lived in the er ceng ge. The cobbler carried his tools to the nearby lanes every day, where he made or repaired shoes to support his family. His wife stayed at home and played mahjong with their neighbors. The bedroom on the third floor was occupied by a 30-year-old woman and her maid. A man working for a newspaper as a proofreader lived on the flat roof. The author lived in the san ceng ge. He used to teach in a primary school, which was later blown up by the Japanese invaders. So he moved up to work as a writer. Every shikumen could be regarded as an epitome of the lower class lifestyles of old Shanghai.

Usually, there is a small room located above the kitchen and below the flat roof, which is called the tingzi jian or garret. Tingzi jian are characterized by poor natural lighting. Being stuffy in summer and frozen in winter makes it the least attractive room in a shikumen house. Tingzi jian were usually rented by companies’ employees, factory workers, apprentices, college students, writers or other people who could not afford better rooms. A lot of famous writers who thrived during the 1920s used to live in shikumen, such as Lu Xun (1881–1936), Mao Dun (1896–1981), Ba Jin (1904–2005) and Shen Congwen (1902–1988), and many great works were created in tingzi jian.

A neighborhood of lanes populated by shikumen houses was called a longtang or lilong. Wandering these three-or-four-meter-wide lanes gives a hint of the magic of the typical Shanghai life. The Shanghainese had dinner, washed clothes and emptied nightstools (bucket-shaped latrines) in the lanes. In summer, shikumen residents often put their dining table at the gate and had dinner in the open. As night fell, many families carried their bamboo couch or chaise lounges to the entrance of the lane, washed them with cool water and rested on them to enjoy the cool temperature.

It seemed that there was no privacy in the alleyway complexes, because living cheek by jowl with neighbors means being involved in each other’s lives. As gossip was traded among the residents, the economic conditions and backgrounds of families in the same complex were not secret. Some believed that the alleyway lifestyle helped forge the character of the Shanghainese.

Alleyway complexes also housed various shops, such as drapers, butchers, chemists or barbers. Alleyways echoed with the shouts of vendors selling snacks and desserts all day long. Most of the snacks and desserts sold were distinctive styles of food from southern China, such as wontons, zongzi stuffed with pork, sweet lotus seed porridge, spiced beans and the most popular of all, stinky fried tofu. These snacks were often delivered in baskets lowered from upper-floor windows. Snack transactions were done quickly without bargaining because the residents and vendors knew each other well.

Although they lived in the narrow alleyway complexes, most of the residents, in particular the middle class and educated people, still had contact with the outside world, influenced by modern civilization from the West. Writers often visited foreign bookstores located in the foreign-controlled zones, where they had access to the latest foreign works. A writer named Ye Lingfeng (1905–1975) recalled that one day in a bookstore, he was attracted by Ulysses by James Joyce and bought this ten-dollar book with only 70 cents. The culture from the outside made people inside more cosmopolitan, and this influence left its mark permanently in the works of the scholars living in the shikumen and alleyway complexes.

The article was edited and translated from Insights into Chinese Culture, published by Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. Ye Lang and Zhu Liangzhi are professors at Peking University.

(edited by REN GUANHONG)