Timeless appeal of the Mid-Autumn Day

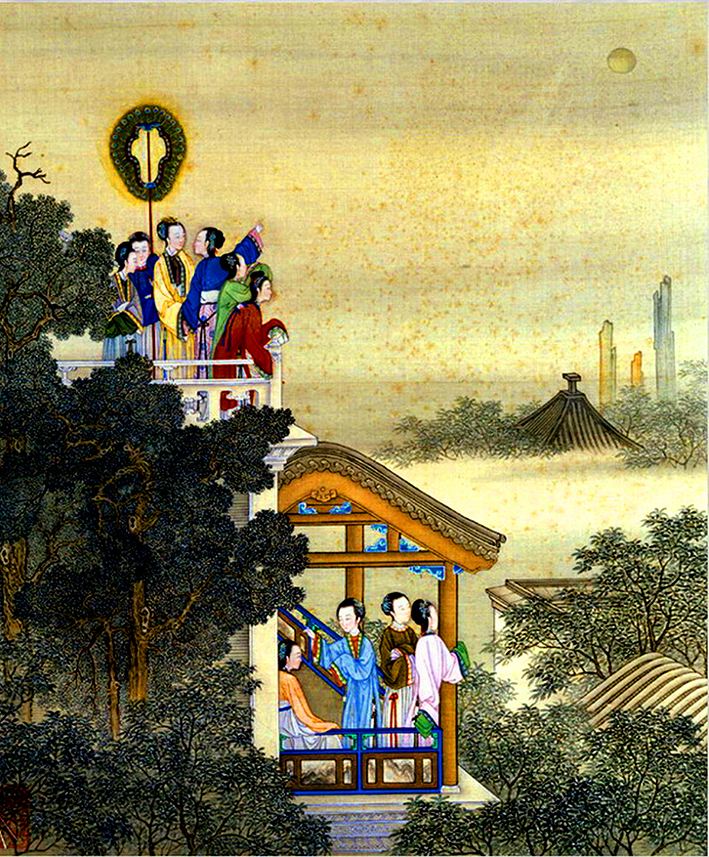

“Appreciating the Moon” (1738) by the Qing artist Chen Mei Photo: FILE

Rooted in Chinese tradition, the Mid-Autumn Festival, also known as the Moon Festival, is second only to the Chinese New Year in terms of its importance. It is celebrated on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month, which is believed to be propitious, because the moon that night is usually at its fullest. In Chinese culture, the full moon is an emblem of a harmonious family relationship, as the Chinese see in its roundness a symbol of reunion and completeness.

Cultural significance

The full moon is the most distinct symbol of the festival. It has been endowed with emotions and feelings throughout the ages. The old saying hua hao yue yuan (May the flowers be in full bloom and the moon be full), which is often used as a greeting during the Mid-Autumn Festival, symbolizes the family life that the Chinese look forward to. Family members return home and do things together, like having dinner, sharing stories and experiences and appreciating the moon. It is said that when one grows up, they might forget what they ate or did during the festival, but they surely remember the feeling of being with their family.

Since the festival mainly celebrates family reunions, people who cannot go back home often feel homesick when they see the full moon. There are a lot of nostalgia-themed poems or writings about the festival. For instance, “Jing Ye Si” (“Thoughts in the Silent Night”) by the great Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai (701-762) is a poem about homesickness. “Beside my bed a pool of light–/ Is it hoarfrost on the ground?/ I lift my eyes and see the moon,/ I bend my head and think of home.” Ji Xianlin (1911-2009), another renowned Chinese writer, also related the moon to his hometown in his essay, “Bright is the Moon over My Home Village.” Ji wrote, “Everyone has his hometown, every hometown has a moon, and everyone loves the moon over his hometown. Presumably, that’s how things are.”

In ancient China, it was believed that there was a supernatural connection between Heaven and the world of mortals. People considered certain natural phenomenon as a reflection of the destiny of human. Since the visible form of the moon always changes, people believed that they followed the same pattern, going up and down. Somehow this belief taught them to be inured to misfortune while staying hopeful for better things to come. As was written in the poem, “Ming Yue Ji Shi You” (“The Mid-Autumn Festival”) by the famous Song Dynasty poet Su Shi (1037-1101), “But rare is perfect happiness–The moon does wax, the moon does wane;/ And so men meet and say goodbye./ I only pray our life be long,/ And our souls together heavenward fly!” Just like Su, the Chinese believe that appreciating the moon on the night of the festival can create a special bond among people, making them feel closer to each other, regardless of where they are.

Origins

It is difficult to discern the original purpose of celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival. According to a generally accepted version, the tradition of celebrating the festival dates back to more than 3,000 years in China, commemorating the end of the harvest season. The earliest record of this custom roots back to the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046-771 BCE), describing how kings offered sacrifices to the moon in autumn, as they believed that the practice would bring them a harvest the coming year.

The term “Mid-Autumn” first appeared in a written collection of rituals of the Western Zhou Dynasty, the Rites of Zhou, probably composed during the Warring States Period (the 5th century to 221 BCE). But at that time the term was only related to the time and season. The festival didn’t exist at that point.

It was in the Tang Dynasty (618-907) that appreciating the moon started to gain popularity, first among the upper class. A legend explains that Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (685-762) started to hold formal celebrations in his palace after his claim that he had explored the legendary Moon Palace. Following the Tang court, rich merchants and officials held big parties in their house on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. They drank wine and appreciated the bright moon in their yards. Music and dances were also indispensable. Commoners simply prayed to the moon for a bountiful harvest. Later, appreciating the moon became a tradition across the whole country.

The 15th day of the eighth lunar month has been listed as a festival by the Song Dynasty (960-1279). A man named Wu Zimu in the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) is regarded as the first to record the day as a national festival, noting it in his work about local customs, Meng Liang Lu. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Mid-Autumn Festival had become one of the greatest events celebrated across the whole country.

Customs

The main celebratory activities during the Mid-Autumn Festival consist of appreciating the moon, eating mooncakes together and playing with lanterns. These three celebrations have been passed down from generation to generation.

It is said that watching the moon on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month became a custom during the Tang Dynasty. People gathered at their homes or restaurants, drinking wine, listening to music and making poems about the moon.

Mooncakes are the most important food of the Mid-Autumn Festival in China. These sweet, round cakes typically have a filling of nuts, melon seeds, lotus-seed paste, Chinese dates, almonds, minced meats or orange peels. The origin of eating mooncakes in the festival is uncertain. Some have associated them with a poem by the Song poet Su Shi. Su mentioned a moon-shaped cake filled with butter and barley malt syrup in his poem, “Liu Bie Lian Shou” (“A Farewell to the magistrate of Lianzhou”). However, there is no evidence to prove the cake in Su’s poem was a mooncake, and the poem seems to have nothing to do with the Mid-Autumn Festival.

In fact, the earliest record of eating mooncakes during the festival dates back to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The traces can be found in many Ming writings. A eunuch wrote a book about the history of the Ming court, in which he recorded that mooncakes had been on sale since the first day of the eighth lunar month. People bought and sent them as gifts, together with watermelon and lotus roots, to their relatives or friends. When the 15th day came, each family offered mooncakes and fruits as sacrifices to the moon. The surfaces of mooncakes were often pressed with designs of Chang’e (a goddess who lived in the Moon Palace), osmanthus trees or the Jade Rabbit (a legendary creature of the moon). The mooncakes were shared during supper, celebrating the festival until late at night. Since the Ming Dynasty, eating mooncakes has been a formal tradition of the festival.

Colorful, brightly lit lanterns and clay rabbits are also highly recognizable symbols of the festival. Traditionally, lanterns functioned as toys and decoration. They were elaborately made of paper and candles, toted by children and hung under the eaves, creating more festive atmosphere. Another tradition involving lanterns is to write riddles on them, with others guessing the answers of the riddles.

Worshipping clay rabbits (tu er ye, Lord Rabbit, literally) was an old tradition in northern China, originating from the Ming Dynasty. It was derived from a piece of Chinese folklore about the Jade Rabbit, based on some markings on the moon that resemble a rabbit. In this folk tale, the Jade Rabbit is an animal that lived on the moon and accompanied Chang’e, constantly grinding with a mortar and pestle to make the elixir of life for her. The earliest reference to clay rabbits can be found in a book written by a Ming scholar named Ji Kun (1570-1642). Ji recorded that during the Mid-Autumn Festival, clay rabbits were popular in the capital city. These clay sculptures were dressed and sat in a squatting position like humans. People put them on the altar and paid respects to them. In the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), clay rabbits became toys and their appearance varied, sometimes holding a flag, sometimes riding a qi lin (a mystical creature with dragon-like features) or a tiger.

(edited by REN GUANHONG)