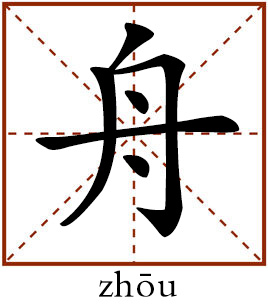

Boats symbolize a drifting life free from restraint

Floating out to the lake or the sea in a raft is a common symbol of a reclusive life in the face of political setbacks, as advocated by Confucius.

In addition to being an important form of transportation, boats in Chinese culture also symbolize the interdependent relationship between the ruler and the people, the sorrow of being separated from loved ones as well as the drifting but unrestrained life.

China has a long history of making and using boats. According to the Huainanzi by Liu An (179-122 BCE), when ancient people saw hollow wood drifting on water, they learned to make boats from it. The I Ching contains sayings such as “cutting wood into boats” and “first designed by the Yellow Emperor.” The densely distributed rivers and lakes across China made boats an important vehicle.

Meanwhile, boats are also admired for being hollow-hearted while carrying heavy burdens, symbolizing those who are modest in accomplishing their mission. They are unadorned and bear hardship without complaint. All these virtues made boats common symbols in Chinese literature since the Book of Songs.

Political philosophy

A well-known metaphor about boats that originates from the Xunzi by Xun Kuang (c.313-238 BCE) goes, “The kings are like boats while the people are like water. The water that supports a ship can also upset it.” This was a frequently quoted metaphor when the ministers admonished the emperors to pay attention to the happiness and sorrows of people. For example, Emperor Taizong in the Tang Dynasty, one of the greatest emperors in Chinese history, frequently used this saying to reflect on his policies and admonish officials.

In addition to the relationship between the ruler and the people, boats also symbolize competent officials who help the emperor govern the nation. The Book of History includes this line, “Morning and evening present your instructions to aid my virtue…Suppose me crossing a great river, I will use you for a boat with its oars.” According to the Shuoyuan by Liu Xing (77-6 BCE), “The kings who aspire to rule the world should rely on people with capability and virtue, and Yi Yin, Lu Shang, Guan Zhong and Baili Xi are the boats and chariots these rulers should seek.”

Just as boats can bear a heavy burden without complaint, a person with these virtues can generally be entrusted with national affairs concerning the public interest. Boats and chariots, together with fine horses, symbolize an excellent person who can help govern the nation and pacify the world in Chinese culture.

When a person has the desire to serve the nation, sometimes they aspire to be introduced to the political circle, which would provide them the fastest way to serve the people. A more high-ranking person appreciative of a subordinate’s abilities is called Bo Le, after the well-known horse-evaluator in the Spring and Autumn Period. For example, in a poem written to his friend Wang Can (177-217), Cao Zhi (192-232), a prince of the Wei Kingdom in the Three Kingdoms Period, said “I wish to keep this bird as my companion; Sadly I do not have a fast boat.” One of several sons of Cao Cao, founder of the Wei Kingdom, Cao Zhi was not the favorite son. Although he planned to introduce his friend to the court, he implied that he had little influence on his father.

Meng Haoran (689-740) waited for an opportunity to serve the nation when he lived a reclusive life. He wrote “I have no boats when aspiring to cross the river.” Boats served as bridges allowing him to depart his reclusive life and move toward a life of service to the nation. Without someone who was appreciative of his abilities, Meng’s dream to benefit the people would be difficult to realize.

Unrestrained life

A drifting boat following the currents of the river echoes the Taoist idea of submitting oneself to the laws of nature. Chaung Tzu once said “With his stomach filled, he drifts, like a boat without a cable.” For him, a boat drifting freely on the water symbolizes a sage unattached to anybody or anything in the world. In this sense, a drifting boat symbolizes spiritual freedom.

Upon finding themselves in a sorrowful situation when they could not realize their life goals in the courts, ancient Chinese scholars would choose to indulge themselves among mountains and rivers, either as a wood-cutter or fisherman. As one Liu Zongyuan (773-819) put it, “A lonely fisherman afloat; is fishing snow in a lonely boat.”

Su Shi (1037-1101) wrote “I long regret I am not master of my own; When can I ignore the hums of up and down? In the still night the soft winds quiver; On the ripples of the water. From now on, I would vanish with my little boat, For the rest of my life, on the sea I would float.” Scholars like Su Shi dissolve their sorrows and forgot all the annoyances of glory or dishonor among the mountains and rivers.

As a song in the Book of Songs goes, “On the quiet Qi river afloat; Is a pine and cypress boat. Driving in a cart I will go, To relieve my grief and woe.” Confucius also said “The Way makes no progress. I shall get upon a raft and float out to the sea.” Floating out to the sea in a raft was a common symbol of a reclusive life.

Fan Li (536-448 BCE), who was worshiped as an ancestor of all businessmen in China, was a military advisor before he stepped down to become a businessman. After he helped the king of the Yue Kingdom win a critical victory over the Wu Kingdom, he refused to serve any longer in the court. Instead, he went boating in the Five Lakes, together with his beloved wife. According to the Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian, Fan noticed that it was dangerous for him to continue serving in the court as the king was ungrateful. The king Gou Jian would no longer adopt his political advice. Therefore, Fan chose to live a reclusive life among the mountains and rivers.

Fan’s story profoundly influenced Chinese scholars. For example, Li Bai (701-762), one of the greatest poets in Chinese history, wrote the famous verses, “Cut running water with a sword, it will faster flow; Drink wine to drown your sorrow, it will heavier grow. If we despair of human affairs; Let us roam in the boat with loosened hairs!” The conflicts between Li’s ideals and the reality could not be resolved under the circumstances at that time. Escaping from the reality and living a free life in a boat drifting on the river seemed the best choice he could make.

According to the Bowuzhi, an encyclopedic record of things by Zhang Hua (232-300), people by the sea noticed that a wood raft appeared in the sea every August. By riding the boat, one was said to be able to reach the Milky Way. Originating from this tale, this unique wood raft bridging human society and the Milky Way became a vehicle for scholars exhausted by affairs in the mortal world to express their dreams of living in an immortal world where people could find inner peace.

Homesickness

It is typical to use a drifting boat to symbolize a drifting life in Chinese culture. A boat in the surging river or sea is like a person facing the danger of being devoured by the social reality. A lonely boat or lonely oar is typical symbol of a drifting life when one tries to make a living, or is busy travelling on the road as a government servant, or unable to reunite with family members back in their hometown. This feeling was stronger when one faced setbacks in their career.

Du Fu (712-770) was a master of this boat symbolism in his poetry. In the later years of his life, Du Fu was “drifting between the Heaven and Earth in the Southwest [of China]” as a result of national turbulence caused by the Rebellion of An Lushan and Shi Siming, which severely struck the Tang Empire. He lived mostly in a drifting boat in his late years and died there. Hence, he frequently used boat symbolism in his poems. For example, he wrote, “Delicate grasses, faint wind on the bank; stark mast, a lone night boat…Fluttering, fluttering, where is my likeness? Sky and earth and one sandy gull.” He describes his own life in a drifting boat as a lonely gull flying between the sky and earth, finding no place to rest.

Another verse by Du goes, “From kinfolk, friends, [I hear] not one word; Old, illness-stricken, [I am] in my solitary boat.” His poem Broken Boat includes these lines, “My boat—gunwales I’ll never thump again—sunk in water a whole autumn by now…Old boat—possibly I could raise it; Or easily enough find a new one. What pains me is having to ran away so often; Even a simple hut I can’t stay in for long!” These lonely or broken boats reflect the drifting and lonely life of his late years.

Zhang Ruoxu (c.647-c.730), in his masterpiece The Moon Over the River on a Spring Night, a long poem admired by Wen Yiduo (1899-1946) to have “surpassed all other poems in the entire Tang Dynasty,” wrote “Where is the wanderer sailing his boat tonight? Who, pining away, on the moonlit rails would lean?” The boats that carry away our loved ones on the day of their departure have come back but not the people. Boats become symbols of a strong desire to reunite with family members, loved ones and friends as well as the reluctance to be separated from them. As Li Bai wrote: “His lessening sail is lost in the boundless blue sky; Where I see but the endless River rolling by.”

(edited by CHEN ALONG)