The changing attitudes towards China’s xia

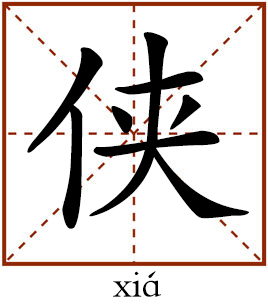

Advocating that a person with martial arts should use his or her power to help the weak against injustice, Chinese xia culture is entrusted with humanistic pursuit of social justice, virtues and conscience.

Xia in Chinese culture refers to a group of people with martial arts skills who act bravely for a just cause and is willing to sacrifice him or herself to rescue those who are in distress and help those in poverty. Chinese xia culture is entrusted with humanistic pursuit of social justice, virtues and conscience and became a unique Chinese cultural image.

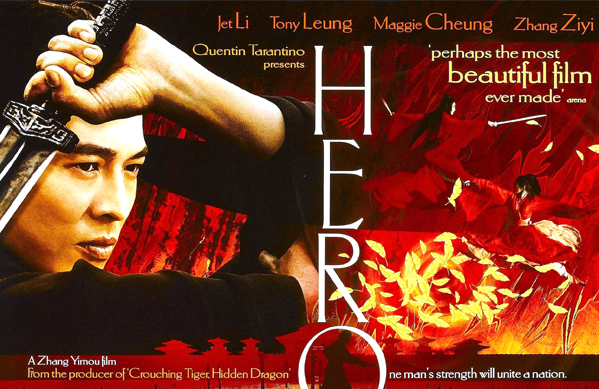

Wuxia, which literally means “martial heroes,” is a genre of Chinese fiction that revolves around the adventures of martial artists in ancient China. In this phrase, wu refers to martial arts. While, according to the Great Chinese Dictionary, xia originally referred to a person with martial arts skills who acts bravely for a just cause and who is willing to sacrifice himself or herself to help others. Originally, they were wandering heroes, but often considered rogue elements in society. As a cultural image in literature, the xia gradually represented the upholding of justice when the laws failed to do so, and was expected to help the weak rather than the strong or wealthy.

Ever since their emergence in the 1950s, contemporary Chinese wuxia novels, represented by prominent writers Jin Yong—also known as Louis Cha Leung-yung (1924- )—and Liang Yusheng (1924-2009), have been popular in China, as well in East Asian countries. The everlasting influence of xia culture has cultural and historical origins.

Historical origins

Xia culture is one of the most controversial domains among all the studies about Chinese culture. There are several reasons for this state of affairs. Firstly, the research materials are scattered while the historical literature is inadequate. Second, the characters that influenced wuxia writing, who wandered the country and helped others, often had complicated personalities and conflicting temperaments, which made it difficult to generalize and form a genre. Another problem is that the rulers of ancient China generally held negative attitudes towards xia for their unlawful actions in defence of justice. Last of all, xia culture carries public idolization of heroes, and the writers had their own ideas about what constituted the ideal personality and what values an ideal xia culture should convey.

There are extensive debates over whether the xia group originated from the Mohist School, founded by Mozi in the Spring and Autumn Periods, or from the disciples of Qidiao Kai, a prominent student of Confucius. Most disciples of Mozi came from the lower classes of society and upheld the concept of impartial care, opposing the Confucian theory of differentiated love. Qidiao Kai, as legalist theorist Han Fei (c.280-233 BCE) commented, “showed neither a yielding look on his face nor evasive wink in his eyes in the face of threat.” Both or either of these groups could be the early ancestors of Chinese xia.

The Records of the Grand Historian and the Book of Han are the only two official historical books that contain records about xia, which indicates the governments’ negative attitudes toward them. However, since the Wei and Jin dynasties, literary works on xia prospered and the image of xia yielded unusually brilliant results. Xia culture stresses what an ideal xia should do rather than the practical actions of these people. In this sense, the evolution of xia culture is a process from a historical to a literary phenomenon, and, ultimately, to the establishment of a utopian concept of enormous cultural significance.

The legalists and the historians were the first two groups of scholars who discussed the xia phenomenon. They generally held negative attitudes towards xia for resorting to violence and vigilante justice.

Most records and discussions on xia in pre-Qin literature were directly related to stories of assassins. Han Fei, the founder of Chinese Legalist School, considered xia to be one of the “five vermin” of the nation in his masterpiece Hanfeizi. He wrote that “Confucian scholars with their writings confuse the law, while xia with their weapons break the rules. The fact that rulers still treat them with courtesy is the root of national chaos.” “Those xia with swords, mustered a gang of people. Flaunting their adherence to integrity and justice, they tried to win high reputations by arbitrarily breaking the laws made by various government departments.”

Another line in this book goes “When one violates the laws, he will be punished in accordance with the laws. When one does not violate the laws [but offend an influential person], he will be dealt with by personal swords.” Xia culture showed a strong influence from assassins in its early development. As a result, both the Confucian and Mohist classics rejected these people and did not record many stories about them.

Sima Qian was the first historian who wrote biographies of the xia. In his Records of the Grand Historian, Sima gave a general overview about xia. He wrote “As for the xia, although they do not always do what is right, their word can be trusted. They keep all their promises, honor all their pledges, and hasten to rescue those in distress regardless of their own safety. They risk their lives without boasting, not stooping to speak of their good deeds. So, there is much to be said for them, especially as anyone may find himself in trouble sooner or later!” In his autobiography attached to the book, which elaborates on his ideas of writing the book, Sima Qian wrote “Rescuing those in distress and helping those in poverty are what a ren (virtuous) person would do. Keeping all their promises and honoring all their pledges are what a yi (just) person would do.”

Ren and yi are two vital virtues highly admired by Confucians. For Sima Qian, xia were, first of all, deviants of the social order. However, he defined those xia people by their personal code of conduct and emotional principles—“righteousness of xia.” Rather than stressing justice in terms of ruling orders or ethical norms, he was able to free himself from the influence of the hierarchical orders demonstrating Confucian ethics and show an tolerant attitudes towards the xia when judging them. Sima’s theory greatly influenced the historical attitudes and literary writings about xia culture in later generations.

In the Eastern Han Dynasty, records about the xia disappeared from the official history books. However, xia culture became a notable topic of literary expression. The abandonment by the historians and the favor from the writers as of the Wei and Jin dynasties elevated the xia to the status of popular heroes. Literary scholars established an ideal personality by complementing xia culture with Confucian virtues and the aristocracy also admired the xia. With the help of literary scholars, the xia culture gradually obtained more social and cultural connotations than what they actually had in real history. The xia were entrusted with humanistic pursuit of social justice, virtues and conscience and became a unique Chinese cultural image.

Responsibility, justice, freedom

Classic contemporary wuxia literature often placed fictional stories against a real historical background. Fictitious martial heroes interacted with the real historical figures and experienced a crucial moment of Chinese history. The readers sharing the collective cultural memory of certain events would follow those heroes who made their noble choices in the face of personal sacrifices as well as national calamity.

Chinese wuxia culture uses history to explore the relationships between individual fate, and that of the family, the community and the nation. Regardless of their personal temperaments or philosophical ideas toward individual existence—Confucian, Taoist or Buddhist—a martial artist can only be called “xia” if he made personal sacrifice for a righteous cause, defending the people, family, community and the nation. The Confucian teachings that encourage a person to “improve one’s personal virtues, regulate the family, govern the nation and pacify the world” are still the guiding principles when judging whether a person is qualified to be called “xia.”

The “wu” in the wuxia requires a person to pay attention to practicing certain martial arts and establish a strong will against injustice. The xia as in wuxia indicates that a martial hero should be sympathetic to the people and do right things by punishing the evil-doers and encourage the people to do good as well as defending one’s family and nation. A sympathetic heart and the sense of honor, shame, justice and responsibility are inherent demands of the prevailing Confucian philosophy.

In addition to the Confucian teachings that stresses responsibility, the Taoist philosophy of following the natural course of things also heavily influenced the xia image. Some of the influential schools of martial arts, including Wudang and E’mei, both in reality and in literary worlds of wuxia are schools based on Taoist philosophy. The theories of yin-yang, five elements and eight diagrams are frequently used in wuxia literature. Transcending the worship of the physical martial arts and fully comprehending the Taoist philosophy of the “harmony between humanity and the nature” is the highest state of wuxia that one could realize. The mastery of a great martial arts requires transcending the physical weapons and a thorough understanding of the Tao. The Tao here is a concept that absorbs the quintessence of major Chinese philosophical schools—from the benevolence, righteousness, love and reason of the Confucianism to the freedom, tranquility, inactivity and simplicity of Taoism and the mercy, benevolence, tolerance and inclusiveness of Buddhism.

The heroes upholding this Tao of life freely venture in the wuxia world and radiate enormous vitality, motivating and leading those who tirelessly pursue the Tao of life in the real world.

(edited by CHEN ALONG)