Ba culture and Ba-style bronzes

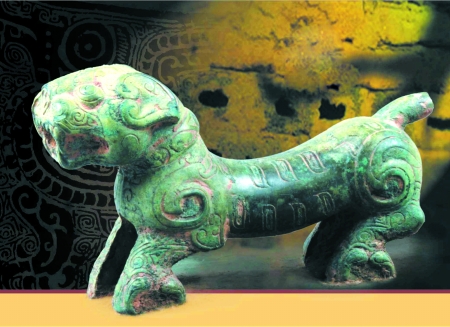

Tiger-handled Chunyu

“Rising in the southwestern mountains,

There is the State of Ba.

Da Hao bore Xian Niao,

Xian Niao bore Cheng Li,

Cheng Li bore Hou Zhao.

Hou Zhao is the forbearer of the Ba people.”

-Shan Hai Jing (Classic of the Mountains and Seas)

So goes the earliest written record of the State of Ba (?-316 BC). From their emergence as a loose confederation of clans till their formal coalition as a state during Pre-Qin period, the Ba people conquered a harsh natural environment and strong enemies in all directions. They traversed all over the Daba Mountains through Sichuan, Chongqing, Hubei, Shaanxi and Guizhou, leaving behind a wealth of moving stories and dazzling legends that their descendants remember still today. After decades of ceaseless battle during the Warring States Period, the State of Ba was eventually conquered by Qin. But though the State of Ba may no longer have been an independent polity, the Ba culture lived on, integrating with the culture of the Qin and Han Dynasties and ultimately becoming an indivisible branch of the extensive and profound Chinese civilization. Chongqing is sweltering in July—the scorching sun looms and heat waves rise from the ground without pause. We braved the menacing heat to travel around sites from the ancient State of Ba and revisit its past glories.

What experts have indicated may be the final resting place of the Ba chieftains is located on a small hillside on the western bank of the Wu River at Xiaotianxi, Chenjiazui Village, Baitao Town in the Fuling District of Chongqing. In fact, the two characters涪陵 (Fuling) literally mean “Fu (river) tombs”, and are derived from the couplet “The Tomb (陵) of the King of Ba/is on the Bank of the Fu (涪) River.” Since 1972, the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Relics and Archeology Research Institute and other institutes have conducted a number of excavations and searches for cultural relics. In total, nine tombs and a substantial amount of cultural relics from the Warring States Period have been excavated.

Today, a single stele marks the site. Erected by the People’s Government of Sichuan Province in 1991, it bears the simple inscription “Sichuan Provincial Cultural Relic Protection Site—Xiaotianxi Tombs.”

Tang Yeze, a researcher from the China Three Gorges Museum, noted that the ancient State of Ba left behind very little that could be found on the ground or in circulation. All of the archeologically excavated pottery, jade, and bronzes are preserved in different museums. Of these, Ba-style bronzes are by far the most representative of the Ba people’s culture and social conditions during the Pre-Qin period.

In the Fuling District Museum, the curator Huang Hai told us that the bronzes left behind by the Ba stand for a part of Bayu (referring to Chongqing) culture. During the Spring and Autumn Period and Warring States Period, construction of bronze vessels flourished throughout the region. Many elements of Ba culture can be understood by observing the shapes and ornamentations on the bronzes. In an exhibition room devoted to these bronzes in the Fuling District Museum, it is apparent that they fall roughly into two categories: housewares and weaponry. All of the works employ cuojinyin, an ancient hand-work technique to coat or paint bronzes with gold and silver, and mosaic techniques.

A significant portion of Ba bronze making culture was devoted to weaponry. More than instruments of violence though, the Ba-style bronze weapons are notable for both their unique shape and their ornamentation. The Ba fashioned swords and spears that resembled willow leaves, tiger striped dagger-axes, and battle-axes with circular blades. All of these designs are exclusive to Ba bronzes, and are in sharp contrast with other regional bronze weaponry. Additionally, the Ba weapons include unusual animal totems and emblems, such as tiger, birds, snakes and even shape of hands.

Particularly representative of the Ba people’s fascination with mysterious beasts is an ancient bronze bell called chunyu. Chunyu are cylindrical at the base and expand to a large orb at the top, giving them a slightly conical shape. At their peak, chunyu have vividly sculpted in the shape of a tiger opening its mouth and thrashing its tail spiritedly, a feature that has earned them the nickname “Tiger-handled Chunyu”.

According to legend, when Lin Jun, one of the kings of Ba, died, his soul transformed into a white tiger. Afterwards, the Ba people revered white tigers, valorizing them with totems. The Tiger-handled Chunyu is a musical instrument unique to the Ba people. Its use was widespread throughout the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-221 BCE) to the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE). When going into battle, the Ba would tie the chunyu onto a wooden frame using the tiger-shaped handles, then strike the large rim of the chunyu, making a clear and resounding noise that lifted the spirits of the brave Ba soldiers, driving their charge forward and urging them to victory.

GuoXiaoya and Wu Yunliang are reporters from WAN.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 483, Aug. 2, 2013

Translated by Zhang Mengying

Revised by Charles Horne

The Chinese link:

http://www.csstoday.net/xueshuzixun/guoneixinwen/83323.html