Ancient bridges: Arcs in dust of time

The Fengyu (Wind and Rain) Bridge at the Maogong County, Guizhou Province (PHOTO: DU JUANJUAN/XINHUA)

The Lianhua (Lotus Flower) Bridge in the Slender West Lake in Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province (PHOTO: ZHANG YOUYUN/CSST)

The Yudai (Jade Belt) Bridge at the Kunming Lake in the Summer Palace (PHOTO: ZHANG YOUYUN/CSST)

The marble Seventeen-arch Bridge in the Summer Palace on the Winter Solstice (PHOTO: ZHANG YOUYUN/CSST)

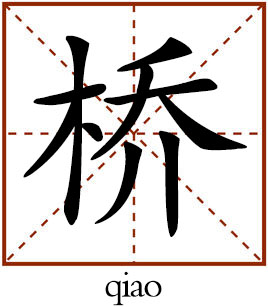

The Chinese character “qiao” means “bridges.” Using materials including bamboo, vine, wood and stones, ancient Chinese developed various forms of bridges, including beam arch, suspension and pontoon bridges.

Water plays a significant role in traditional Chinese culture. Where there is water, there will be bridges. Bridges in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, where small rivers are densely located, are like elegant lines sketched on white paper. Bridges over the streams in the mountains and forests surround the sounds of nature between heaven and earth. Bridges over the steep valleys have serpentine arches evocative of the passionate dancing of dragons.

Bridges in China first take the form of “liang” (beams). The word “liang” was originally taken to mean the small dams that were built by piling up stones or earth, for the purpose of catching fish. According to the Bamboo Annals, a chronicle unearthed in 279 that covers history from the earliest legends to 299 BCE, the Emperor Mu of Zhou (r. c.976-c.922 BCE) used yuantuo (Asian giant softshell turtles) to build floating bridges. However, these bridges were not actually bridges “over” the river. The later development of ironware promoted the construction of bridges in China.

There are over 1,500 rivers with a catchment area of over 1,000 square kilometers in China. Bridges are crucial to the unobstructed connection of all kinds of roads, which are vital to the development of China. Chinese technology for building bridges continued to advance as demands for bridges with various functions grew. Bridge construction became easier with the development of engineering in deep water, but the needs imposed on bridges grew, with myriad forms of bridge emerging, and construction over ever-longer distances.

Various forms of bridges were developed by ancient Chinese people, including beam, arch, suspension and pontoon bridges. Ancient engineers scientifically utilized the properties of the construction materials including bamboo, vine, wood, stones as well as cast and wrought iron. Years of experience and the flexible way of suiting the measures to local conditions, both geographical and seasonal, helped build various forms of bridges, some of which still silently stand vigil over rivers.

The fengyu (wind and rain) bridges of the Dong people are unique in Chinese bridge engineering. Most of them have been built in the pavilion-tower style. On the long corridor of the bridge, there are several pavilions and towers that usually have three to five floors. Exquisite rails and benches were designed on the bridge for resting and welcoming guests. They were primarily made from the wood of China firs, and Chinese mortise-tenon joints, instead of iron nails, were used to connect the materials.

The fact that bridges leap over the rivers means they cannot weigh very much. In the years before the Industrial Revolution, there was little that could be done to reduce the weight in terms of the construction materials. Ancient Chinese invented the arch structure which made long-span bridge possible. However, lengthening the span of a bridge was done at the cost of its integration. The arches that were supported by the bank pier carried both the weight of the bridge and the load. Hence, the stability of a bridge relied on the foundations and base stones. Theoretically, with the base eroded by water for years, no stone-arch bridges could last for a long time.

Wars were another major factor contributing to the damage of bridges. For example, in order to delay the Japanese invasion, Chinese bridge engineer Mao Yisheng (1896-1989) blew up his masterpiece, the Qiantang River Bridge at Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province in 1937, three months after it was opened to traffic. Since the ancient times, bridges have been closely related to people’s lives. Bridges witness history and tell stories of the people. A bridge is a window into local history and life.