Unbalanced childhoods, dim futures

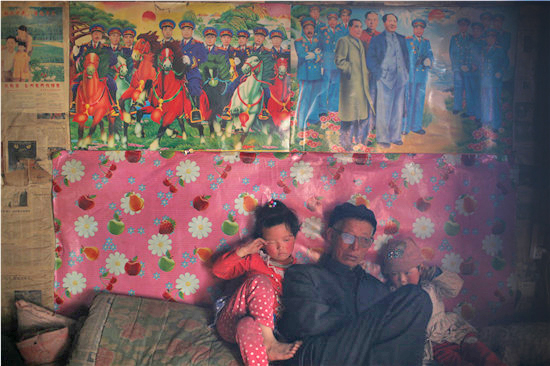

Leaning against the wall, two children, left behind by their migrant-working parents, rest after dinner together with their grandpa.

Lu Jiayan’s mother sued her husband because he has never returned home to be with her daughter.

It is hard to say whether her desires here are simple or complicated. When she went to court, she was only seven years old, a little girl who has lived in a world with an absent father. Just 15 days after she was born, her father Zhao Binwei left home saying: “I need to find something to live off.” He then disappeared. Lu thinks litigation is her only way forward.

Extravagant hope

In Blackstone Town, Weining County, Bijie city in Guizhou Province, where Lu Jiayan grew up, there are 841 left-behind girls like her. In the broader Bijie city area there are 260,000.

These children all hope for their parents’ return.

One evening, during a ceremony focused on left-behind children at the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Hall in 2012, some left-behind children from Jiangxi Province called their migrant-working parents from afar. On another occasion, the Education Commission of Yubei District of Chongqing Province organized 500 representatives for left-behind children to write letters to their parents in the hope that they could stop work overtime and return home in time for new year’s celebration. The words of a nine-year-old boy were published in a newspaper: “Mom and dad, where are you? I miss you so much.”

Since it ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1992, China explicitly stated that both parents and other statutory guardians should consider their children’s best interest as their main concern. A child’s right to reunite with family members has long been part of the law. However, to many children, a reunion with their parents is an extravagant hope.

Gone parents

The court date was March 26, 2016.

Zhao Binwei did not appear in the defendant’s seat, the same way as he has been absent from his daughter’s life. The auditorium was also almost empty. For most of the citizens of Blackstone town, it was just a usual winter afternoon, a time when they routinely do the airing and drying of clothes in the sunlight.

In this town of less than 50,000 people, a child who had been abandoned by his father was not a rare occurrence.

Since the end of 1990s, when people began to come out of their hometown, this small town hidden deep in the mountainous region of Guizhou Province has constantly supplied labor for other areas.

The street seems to be a little empty at night—every one of the roller shutter doors has been closed. Behind those doors, the elderly are holding their grandchildren close to them. A few clusters of teenagers can be found under the street lamps.

The blue light emitted by a mobile phone lights up the teenagers’ faces. Dean of the College of the Humanities and Development Studies at China Agricultural University Ye Jingzhong said he often saw such blue lights at night. “Children playing with their mobile phones are everywhere,” he said.

Parents who leave home feel they owe too much to their children and to make up for their guilt, they buy mobile phones for their children who indeed have nothing else to do, Ye said.

Loss of education

“To left-behind children, the loss of family education is almost irreversible. School education is to prepare for exams but a person’s outlook toward society and human life is decided by their parents,” said Ye, who has been expressing concern about the issue for over a decade. “The values of young people will impact the stability of society in the future.”

But today, the crowds of people flowing outward have destabilized the family structure. The intimacy and affinity between left-behind children and parents are withering.

A lack of education is only one of the scars that the gone parents leave behind. More and more migrant workers mean one hollow village after another.

Some changes are taking place. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the total number of migrant workers in China has been dropping since 2001. However, this change in the data is still far from being sufficient to transform the situation caused by the significant population flows that have occurred for the past more than 30 years in China.