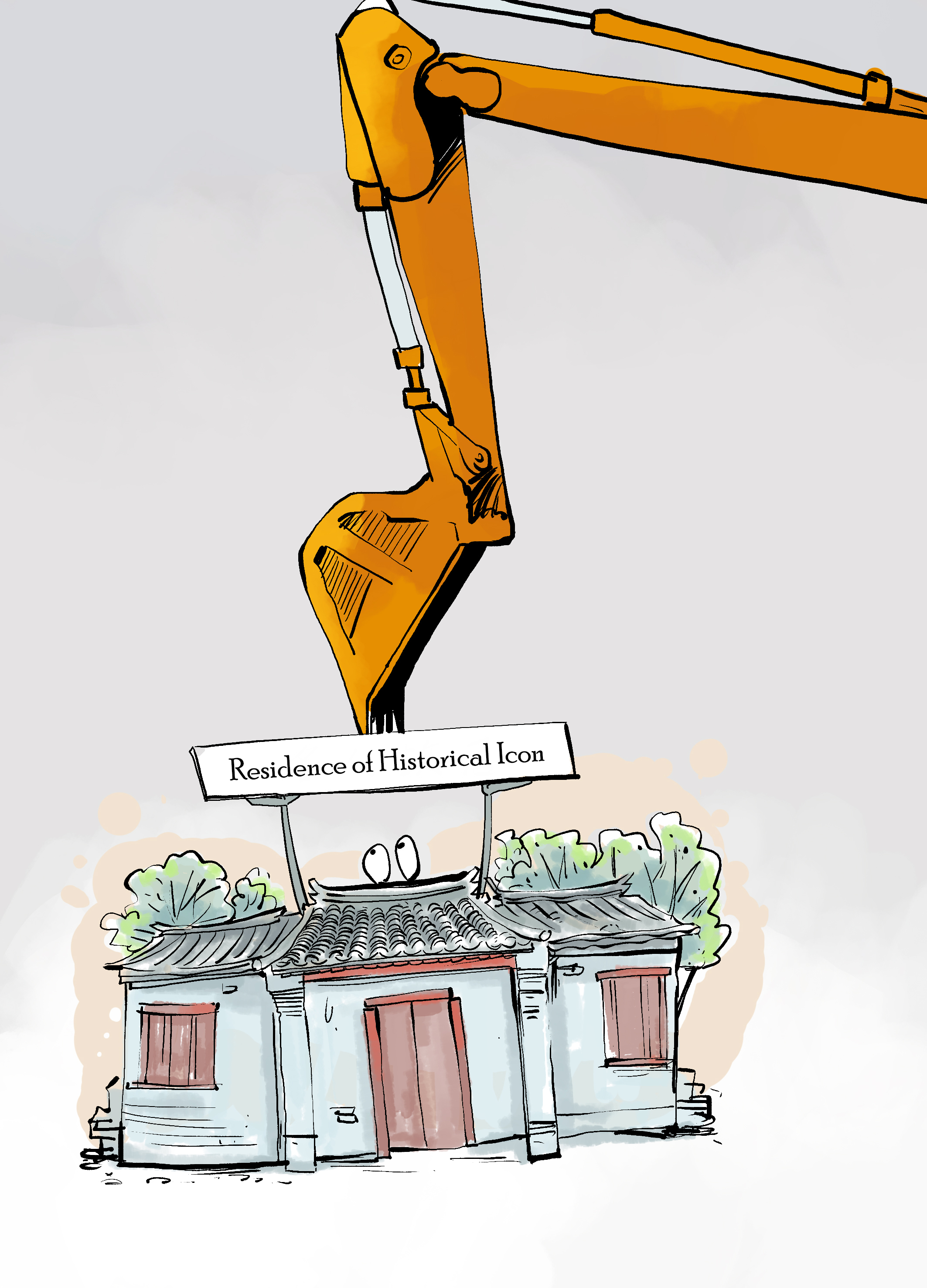

Long neglected, residences of historical icons need urgent conservation action

Demolishing history

Cartoon by Gou Ben; Poem by Long Yuan

The digger dismantles a site,

And the abode of luminary is ruined overnight.

The quaint courtyards of days gone by,

Are where the roots of a city lie.

The residence is a living record

Of past glory,

Bearing silent witness to a forgotten story.

Not just the story of a famous life,

But of changing times,

With all their triumphs and strife.

The issue of conservation

Is an urgent task across the nation.

If cultural elements could be revived,

The courtyard may once again “come alive.”

“To tear down a gate tower is like slicing off a piece of meat from me, and to dismantle a brick from the outer city wall is like stripping off my skin,” said Liang Sicheng, the famous modern Chinese architect who calls for the preservation of the historic buildings in Beijing half a century ago.

At present, China is in a stage of rapid urbanization and development. The former residences of historical luminaries, an important type of historical building, are confined to an increasingly narrow space of existence.

Scattered throughout the urban landscape, these homes have not only borne witness to the lives of famous people but also reflected changing times in which they lived. Many people deplore at the fact that former residences such as that of Tian Han, the modern Chinese playwright, have been destroyed.

According to official statistics, among all the 360 cultural relic sites in Beijing’s Xicheng District, nearly half have been modified for residential use or face other potential hazards.

Though some of the residences are preserved in their original condition, changes in the geographical environment have brought about a status quo for protection that is far from satisfactory.

The courtyard of No. 13, Xiguan Alley, Dongcheng District, of Beijing is where Tian Han had lived for 15 years. From 1953 to 1968, he created a number of influential works there.

The days when refined literati and scholars gathered in the courtyard for discussions are long gone. The last vestiges of cultural elements have left the place. According to earlier media reports, various privately built makeshift shelters and sheds have masked the original form of the courtyard, where sundries are stacked everywhere, leaving behind only a narrow space.

In fact, in Beijing, there are many other historical residences in a similarly appalling state as the former residence of Tian Han. Visiting these residences, the reporter encountered a conservation worker surnamed Liu who said building the cultural sensibility of a city is not a task that can be completed in a single day.

“It is accumulated throughout the process of a city’s historical transformations,” he said, “When a luminary’s former residence vanishes, a cultural symbol disappears and that is irreversible. Citizens become alienated from the city’s historical culture.”

Liu continued: “A city’s memory should extend beyond the glory of the present moment. A city without cultural heritage will become mediocre despite its economic and social prosperity.”

Despite growing calls to rescue these historical building, the disparity between cultural and economic value makes protection a controversial issue in the context of urban transformation. Some argue that commercial exploitation is a better way to make full use of these residences’ economic value.

To some experts, the definition of a “luminary” remains an issue of vagueness. There is a lack of related laws and regulations that precisely define who constitutes a “luminary” or what is a “former residence of a luminary.” In addition, the current standards for application procedures and selection mechanism of the residences need to be improved.

Besides, due to historical factors, inside quite a number of former residences of celebrities, there is only a plaque hanging on the gate identifying it and many courtyards are full of residents. Some complained to the reporter that since the sites are recognized as cultural relics, protection should be vigorous, but now there are no protective measures other than the plaque.

The eldest grandson of Tian Han once said that the old houses inside the courtyard where Tian Han lived are not in bad condition. If the temporary buildings are dismantled and some repairs are made, the courtyard could be revived, he said. But he added that it was nevertheless hard to get such work done.

Some of these sites had already become tenements before they were officially identified as the former residences of luminaries. Given the complexities of tenancy agreements, difficulty of eviction and the large amount of funding needed for restoration, it is hard to protect such residences, said Sun Jinsong, the director of the Cultural Council of the Xicheng District, Beijing.

In addition to protection, how can the humanistic atmosphere inside these residences be made truly tangible for citizens? This is another question worth pondering.