Interpreting Zhang Xueliang’s lonely life

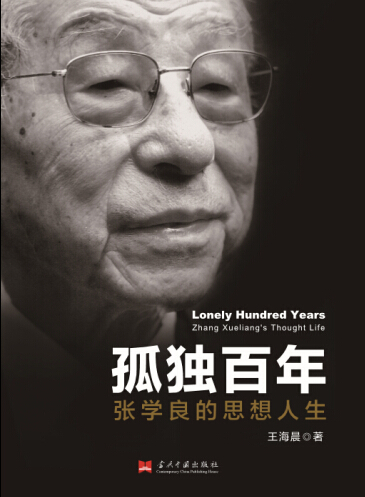

Lonely Hundred Years: Zhang Xueliang’s Thought Life

Author: Wang Haichen

Publisher: Contemporary China Publishing House

Born in an influential family with remarkable social status, Zhang Xueliang (1901-2001), nicknamed the “Young Marshal,” seemed to have no reason to feel lonely. However, after reading Wang Haichen’s new book Lonely Hundred Years: Zhang Xueliang’s Thought Life, readers may be deeply impressed by the Young Marshal’s “hundred years of solitude.”

The book analyzes 145 pieces of Zhang’s dictation and challenges traditional methods of writing, increasing the readability of the academic monograph. Wang gave the book the title “Lonely Hundred Years” as he is familiar with Zhang’s life. In order to probe into Zhang’s thoughts, Wang investigated the places in Taiwan and Mainland China where the Young Marshal was under house arrest. He researched Zhang’s telegraph messages, letters, diaries and various dictations, and examined Zhang’s views on the nation, Japan, war, history and religion, concluding that Zhang’s life was characterized by loneliness.

Zhang Xueliang’s solitude started with the assassination of his father Zhang Zuolin. The title “Ruler of Northeast China” passed to the younger Zhang at the age of 28. At that time, the chances of victory for the Northeast military were slim. The politics and the economy in that region were on the edge of crisis and bankruptcy. Confronting external threats from Japan and Russia and internal pressure posed by the traditionalists, Zhang had no one to turn to. He recalled this period of memories and said that he felt intense pressure that he had to make a decision on many hard situations that would put the whole nation at stake.

The Mukden Incident left Zhang Xueliang in spiritual isolation. This is proven by the fact that Zhang regarded the date as the beginning of a year in his diaries. He was fiercely blamed for his Non-Resistance Policy, which led to Japan’s occupation of Northeast China. Rather than explain himself, Zhang chose to bury the huge pain deep in his heart.

As someone who could influence history, Zhang witnessed turning points in modern Chinese history, and undertook heavy responsibilities during major historical events. After the Xi’an Incident, Zhang was confined in deep mountains, ruined temples and on isolated islands. He had a strong desire to contribute to his nation, but at the same time wished for an ordinary life.

Wang draws parallels between Zhang and Si Maqian (145-90 BC), Ji Kang (224-263) and Li Qingzhao (1084-1155). He contends that Si Maqian’s solitude is echoed in his Records of the Historian. Ji Kang dissolved his solitude in wine and shared it with his friends. Li Qingzhao placed her loneliness in autumn fallen leaves in Hangzhou, and sang it out in her poem Slow Slow Sang. Yet Zhang Xueliang could do nothing but bury his solitude deep in his heart.

LINK

The Xi’an Incident of December 1936 took place in the city of Xi’an during the Chinese Civil War and the war against Japan. The incident led to a truce between the Nationalists and the Communists so as to form a united front against the threat posed by Japan.

The Mukden Incident was a staged event engineered by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the Japanese invasion in 1931 of northeastern China, known as Manchuria.