Putting Chinese culture on global stage

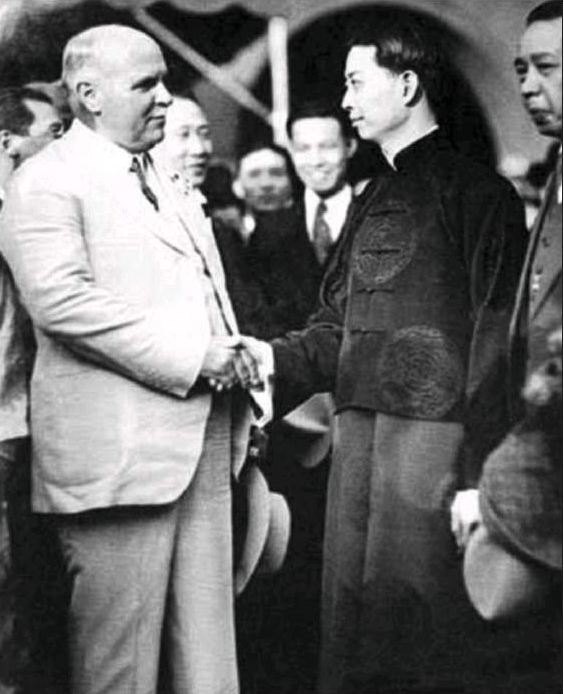

Mei Lanfang, together with his delegation, receive a warm welcome from James Rolph Jr., mayor of San Francisco, when touring the United States in 1930.

The globalization of Chinese culture marks a significant milestone. Such attempts, both theoretically and practically, have been made by previous scholars, and this article explores the idea from several aspects.

In its history stretching back thousands of years, China never worried about spreading its culture to the outside world during times of prosperity. Countries from all over the world took the initiative to learn from China. Japan sent envoys to study China early in the Sui Dynasty (581-618) and the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

At the same time, China actively absorbed the essence of other cultures. Folk musical instruments, such as the pipa, the suona horn and the dulcimer, were introduced from places along the Silk Road. Jinghu is the leading instrument in Peking opera. The two Chinese characters constituting the word refer to Beijing and a northern barbarian tribe. Thus, its name reveals that the instrument is a product of ethnic integration and cultural exchange.

Fine traditional Chinese culture has certain implicit characteristics. It contains strength within peace and tranquility, advocating harmonious relations among people as well as the peaceful coexistence of people and nature. Therefore, we should explore the diffusion of external culture in Chinese history before discussing how to globalize Chinese culture.

Religion constitutes an important part of China’s cultural integration. Buddhism was introduced from India around the 1st century and became popular in China. Its constant development in China as well as in Southeast Asia is attributable to its integration with the local culture and innovative transformation over the past 2,000 years. Similarly, it was the Jesuits rather than the Chinese who translated and introduced Chinese dramas to Europe. The Jesuits believed that they could improve their missionary work in China by studying the cultural lives of Chinese people.

Today, numerous emerging products are very popular, but they are not worthy to be called culture. They obscure traditional culture in the public eye, thus blocking progress. Such a problem exists not only in China alone but also in every other country.

Modern technology and commercial value can be automatically spread without propaganda. Fine traditional Chinese culture represents the cumulative development of lifestyles and modes of thinking over thousands of years. It is the wisdom and experience of Chinese people that has been adapted in harmony with nature and social development. It is of incredible importance to the present and the future. We should maintain the cultural alternative so that future generations have the ability to choose.

The experience of Tu Youyou, the winner of 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, shows the importance of traditional culture. Inspired by ancient documents of Chinese medicine, Tu discovered artemisinin and applied it to the treatment of malaria, saving millions of lives. Artemisinin therefore was called “a gift of traditional Chinese medicine to all mankind.”

Each time period has its own mission and challenges in terms of globalizing traditional Chinese culture. In the 1920s, Mei Lanfang was invited to perform Peking opera outside China. His original intent was to “understand the competitiveness of Chinese opera in the world.” From 1929 to 1930, his half-year tour of America brought with it huge influence. Though the box office failed to cover the expenses, it changed the American misconception that “all Chinese in America are gold diggers.”

Today, it is a struggle to preserve traditional Chinese culture within China and introducing it to the outside world is even more of an arduous task.

The globalization of traditional Chinese culture is strategic. The American cartoon series Kung Fu Panda hit the whole world. In addition to featuring two cultural aspects closely associated with China, the cartoon was also inspired by distinctive folk elements in painting movies from the 1950s and 1960s. As a result, Chinese audiences contributed to the huge box office returns.

Organizations for cultural research and inheritance should devote themselves wholly to sorting out the great legacy of traditional culture. Meanwhile, we should draw lessons from other countries. Only in this way could we have creations that can stand the test of time and the qualification for spreading our own culture. It is a task that brooks no delay.

Zhang Yifan is from the Institute of Chinese Opera at Renmin University of China.