Buddhism challenged Confucianism in Northern Song

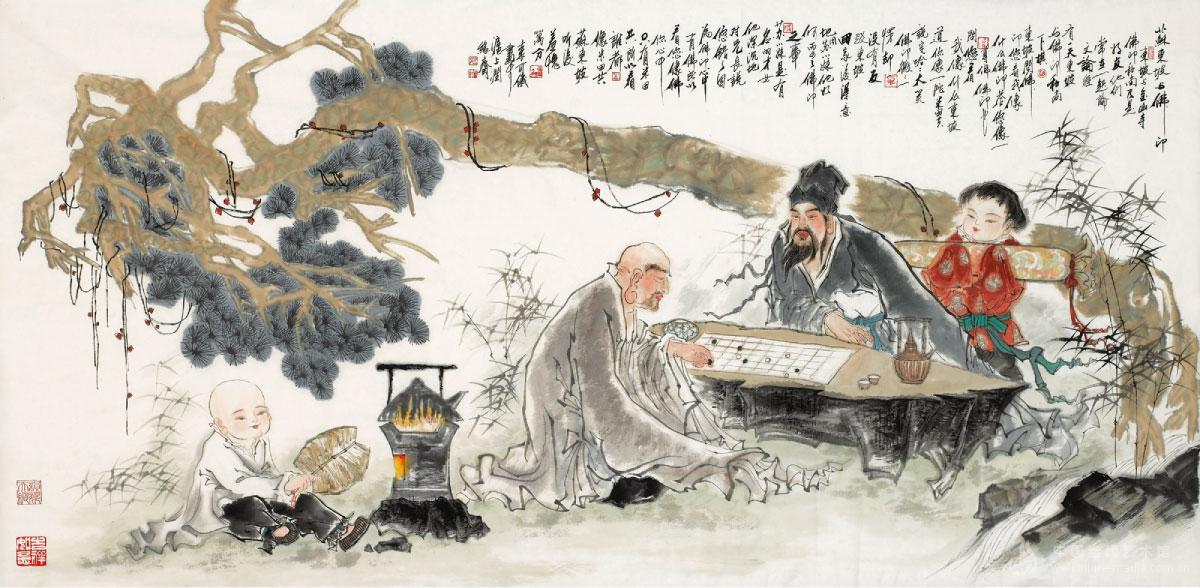

Famed Northern Song litterateur Su Shi plays chess with eminent monk Foyin. Scholarly interest in Buddhism expanded the clout of the religion.

Confucianism was the dominant value system in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). However, the robust development of Buddhism at the time posed a challenge to its dominance, leading the central court to take measures to curb its influence.

Rise of Buddhism

Buddhism was introduced to China in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220) and gained ground over the following centuries by penetrating the imperial court. By the Tang Dynasty (618-907), it had become so popular that its influence on the ruling elite was even greater than that of Confucianism.

During the tumultuous Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdom Era (907-960), uncertainties and hardships fostered a need among the public for mental comfort and relief from pain. They longed for a bright world free of strife that could give them mental and material peace.

By catering to these needs, Buddhism attracted a growing number of followers. In the Northern Song Dynasty, the ruling class continued to bolster the development of Buddhism.

For example, Song Emperor Taizu (reigned 960-975) paid a visit to the Grand Xiangguo Monastery in modern-day Kaifeng, Henan Province, shortly after he ascended to the throne. It is said that when Emperor Taizu came to the statue of Buddha, he asked an abbot whether it was necessary to bow down. His visit and act of reverence demonstrated an acknowledgement of Buddhism’s legitimacy.

After Emperor Taizong (reigned 976-997) came to power, he also visited the Buddhist temple quite often, overtly expressing his support of Buddhism.

In 983, the grand project of translating Buddhist scriptures was finished. The emperor deemed Buddhism beneficial to politics to some extent, maintaining that those who understood Buddhism could sense its benefits, while those who failed to understand it could do nothing but defame it.

Emperor Taizong believed the management of the masses was also a spiritual practice. If the emperor governed well, he could benefit the whole country, thus embodying the spirit of altruism expressed in Buddhism. But for ordinary people, Buddhist practice was only a means of self-cultivation and had little external impact.

The emperor should be partial to no one, have no clique of his own and uphold the proper social order. If he could live up to this ideal, he would also be cultivating himself, Taizong said. The views of the ruler were normally influential, so more people began to practice Buddhism. None of the other emperors in the Northern Song Dynasty opposed Buddhism openly. They all supported it in one way or another.

Challenge to Confucianism

The support emperors gave to Buddhism presented a challenge to the dominant Confucian paradigm. Buddhism not only garnered the support of the upper class but also satisfied the people’s psychological needs. The popularization of Buddhism was inseparable from a host of eminent monks.

Qisong was a renowned Buddhist figure in the Northern Song Dynasty. He held that Buddhism surpassed Confucianism and Taoism in the theory of life. He also advocated that all living creatures were equal, arguing that barbarians and animals enjoyed equal rights to live. The theory considered the needs of ethnic groups and therefore won their recognition.

Some Buddhists also started to absorb elements of Confucianism, interpreting Buddhism’s “Five Disciplines,” namely commitments to abstain from harming living beings, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying and intoxication, by means of Confucianism’s “Five Constants”—humaneness, righteousness, proper rite, knowledge and integrity.

This way, Buddhism was rendered more approachable, thus threatening the dominant status of Confucianism.

Buddhism proposes emptiness and upholds karma, insisting that all beings are equal and can become Buddha. Its unique insight into life drew the attention of many Confucian scholars. In the early Northern Song Dynasty, almost all military officers believed in Buddhism. By the middle and later periods of the dynasty, civil officials and intellectuals like Wang Anshi (1021-86) and Su Shi (1037-1101) had also become Buddhists.

The attention of the scholar-bureaucrat class to Buddhism, whether approval or disapproval, expanded the clout of the religion to some degree.

Buddhism dealt a blow to Confucianism first because the Buddhist theory of karma conflicted with the Confucian moral value system. Buddhists believe that the current order is determined by karma. As long as you do good deeds, you will get good results. According to Confucianism, all actions are governed by ethics and rites, which are unchangeable.

Second, in the Confucian moral spectrum, the social order had been moralized, legitimizing inequality. Except for the imperial examinations, which offered social mobility to intellectuals, most commoners lacked the ability to rise above their station. On the contrary, egalitarian Buddhism afforded each of them the possibility of becoming Buddha.

Other Buddhist doctrines also violated Confucian ethics. For example, the practice of ordinary people leaving their families to become monks or nuns clashed with filial piety, a core tenet of Confucianism.

Government control

Despite the growing influence of Buddhism, the ruling class of the Northern Song Dynasty in fact pursued policies that integrated Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, which highlighted the need for differentiated management of the three schools.

The central court built a number of Taoist temples and published Taoist books and records, lending support to the religion.

Although Buddhism was endorsed by emperors, needed by the populace and learned by intellectuals, the government never adopted a laissez faire attitude. Instead, it imposed restrictions on the religion for political and economic reasons.

During its development, Buddhism produced political beliefs that were at odds with Confucianism and Taoism. In addition to its conflict with filial piety, a key virtue in Chinese culture, Buddhism pays most respect to Buddha, while Confucianism upheld imperial authority as the pinnacle of the Heavenly order.

Considering Buddhism a potential threat to the stability of imperial power, the government therefore took measures to suppress it.

In 1118, when Emperor Huizong (reigned 1101-25) was on the throne, the central court promulgated a decree ordering the purge of any content found in the 6,000 volumes of Buddhist scriptures that violated Confucianism and Taoism. Consequently, nine volumes were burned.

Meanwhile, minority regimes took advantage of Buddhism for military espionage. According to historical records, Khitans, a nomadic people originally from Mongolia and Northeast China, used spies to infiltrate Mount Wutai, a sacred Buddhist site, to obtain military intelligence.

Economically, Buddhism accumulated prodigious financial resources for its bourgeoning development in the Northern Song Era. During the reign of Emperor Huizong, the number of monks, roaming Buddhists and monastic staff members reached 1 million. The large Buddhist population, if left unmanaged and permitted to evade taxes, would considerably reduce state revenues.

It is thus reasonable that the Northern Song court brought Buddhism under strict control. For example, religious activities were banned at night and large-scale religious campaigns were prohibited among the commoners. Monks were also incorporated into the household registration management system and ordered to bind themselves to certain monasteries. There were even limits placed on the number of monks in a monastery.

The stringent management of Buddhism not only restricted some Buddhists from ideologically attacking predominant Confucianism but also sustained the coexistence of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, ensuring regular social and ideological order in the Northern Song Dynasty.

Jian Mantun is from the Administration Bureau for Organs Directly under the Authority of the Communist Party of China Central Committee.