Forgotten Translation of Classic

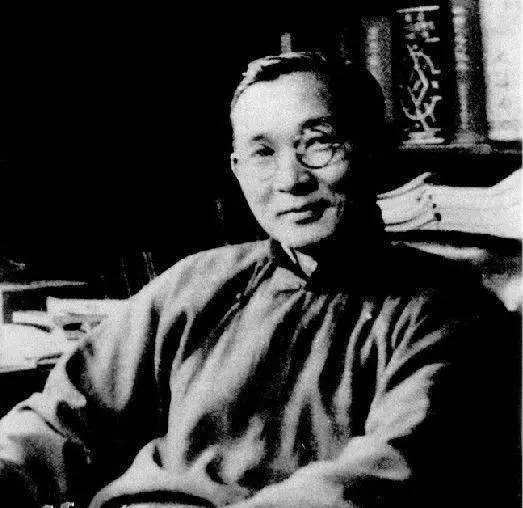

Lin Yutang (1895-1976) is a famous Chinese writer, translator, linguist and scholar.

The novel Dream of the Red Chamber by Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) writer Cao Xueqin (c.1715-c.1763) is one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels, and it has been translated into English many times. Recently, Nankai University announced that it had discovered renowned Chinese writer and translator Lin Yutang’s unpublished English translation, titled The Red Chamber Dream, in Japan, sparking a debate in academia.

Discovery

Song Dan, who is currently an assistant professor from the Japanese Department at the College of Foreign Languages and International Studies at Hunan University, discovered the work while preparing her doctoral thesis for the College of Foreign Languages at Nankai University.

Song specializes in Japanese translations of Dream of the Red Chamber. In her research, she found that Misaki Sato Ruuchi, a famous Japanese translator, used Lin’s The Red Chamber Dream for his Japanese version.

The discovery surprised her, because academics were under the impression that Lin had planned to translate Dream of the Red Chamber in the 1930s but later abandoned the idea because he felt it was not the right time, so he wrote Moment in Peking instead.

Song therefore set out on a quest to find out if Lin had really translated Dream of the Red Chamber.

In 2014, as an exchange student, she was sponsored by Nankai University to go to the Graduate School of Letters at Waseda University. After much digging, she got in touch with the guardian of Misaki Sato Ruuchi’s wife Sato Masako and was told that she had donated her late husband’s collection of books to a public library in Japan.

After asking the library, Song knew that there indeed was a typewritten manuscript of Lin’s The Red Chamber Dream in the catalogue that Sato Masako made. Nevertheless, Sato Masako told the library not to make the books public when she was still healthy, so the library sealed up the collection.

“After many correspondences and obtaining the guardian’s permission, I finally saw Lin Yutang’s original manuscript. It was accompanied by a letter from Sato Masako saying this version was the original copy sent by mail and that Lin Yutang sent the revised draft to them several months later,” Song said.

Then Goyama Sawamu, a chair professor at Kyushu Unviversity, was entrusted with mailing the draft as well as other books, materials and letters to Lin’s house in Taipei, she added.

Lin should have been very cautious about his translation, but why did he give the draft to others when it had not yet been published? Song said that Lin and Misaki Sato Ruuchi had been friends for more than 20 years, so Lin trusted him. Before translating Dream of the Red Chamber, Misaki Sato Ruuchi had translated Lin’s Moment in Peking, The Vermilion Gate and Miss Tu, which Lin had published and mailed to him.

“It is easy to verify the authenticity of the manuscript,” Song said. “First, there are a large number of notes written by Lin Yutang on the manuscript, and the handwriting is the same as that on the manuscripts at Lin Yutang’s house in Taipei. Second, Lin Yutang had translated Taiyu Predicting Her Own Death, a work studied by many researchers, which appeared in The Red Chamber Dream.”

Misaki Sato Ruuchi was a famous Japanese translator, former president of the Japan Association of Translators, recipient of an international translation prize and translator of around 170 works. In light of his skill and reputation among Japanese translators, he would have no need to produce a fake, Song said.

Furthermore, on the title page and the first page of Chapter 29, Misaki Sato Ruuchi wrote “Nov. 23, 1973,” the date when the manuscript arrived, and Lin entrusted him with the task of translating it into Japanese and publishing it in Japan in around two years.

Afterwards, Song went to Lin’s house in Taipei again. Though she didn’t find the revised draft mailed by Goyama Sawamu, she saw the letter that Goyama Sawamu wrote to Yang Qiuming, the curator at the time.

In the letter, Goyama Sawamu mentioned that the English manuscript had not been published and that it was so precious that he hoped it was deposited for safekeeping.

Lin’s version

There are two famous English translations of Dream of the Red Chamber. One, titled The Story of the Stone, was by British Sinologist David Hawkes and the other, titled A Dream of Red Mansions, by Chinese translator Yang Xianyi and his wife Gladys.

Lin’s manuscript that Song saw is printed on one side by typewriter. It has 859 pages and is about 9 centimeters thick. Lin left many notes in black, blue and red ink and there was also a two-page handwritten English manuscript. On the title page, the title is translated into The Red Chamber Dream with an annotation “A Novel of a Chinese Family” in brackets under it.

After reading the English version by Lin and the Japanese version by Misaki Sato Ruuchi, Song said that Lin’s version has several characteristics that distinguish it from the versions by Hawkes and Yang.

First, compared with the Hawkes and Yang translations, there are fewer footnotes in Lin’s work. Lin explained some obscure facets of traditional Chinese culture and plots through sparse commentary in the translation text.

Second, Lin paid much attention to the completeness and continuity of the structure of each single story. For example, from Chapter 71 to Chapter 87, Lin deleted all content that did not have a direct relation to the story and retained the related parts, and then the translation was a relatively complete and continuous story.

Third, the strength of Lin’s interpretation can be seen in phrases that are particularly hard to translate. For example, in Chapter 33, when an old lady misheard “yaojin,” meaning “urgent,” as “tiaojing,” meaning “to commit suicide by jumping into a well,” Lin smartly translated the two phrases into “shoot inside” and “suicide.” Lin not only restored the word sounds of the original text but also integrated the translations with the context organically.

Translation controversy

Lin contended in the foreword that “The best translation is the one that is read not like a translation.” Different from Hawkes and Yang, Lin tended to translate the book with simple English and pay more attention to Western readers’ sensibilities.

In the foreword, Lin mentioned Western readers’ habits several times and expressed his hope that his translation would be accessible. Song said that Lin’s version amounts to a digest of the original text because he deleted or simplified many inessential characters, redundant events, and Chinese poems.

Because it is abridged, it is not as faithful as possible to the original text like a complete translation, Song said.

Lu Jiande, director of the Institute of Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said it is a pity that Lin Yutang abridged the book because its value was diminished in the process. To abridge means to rewrite to some degree, but the classics should not be trifled with, Lu said.

“We have to read the typescript to know whether it retains the charm of the original text and is translated well. The idea that Lin’s translation must be excellent is not totally right. Nonetheless, this is a significant discovery, especially for those who study Lin Yutang and the history of the translation of The Red Chamber Dream,” Lu said.

Japanese writer Okuno Shintaro said that complete translation is like a cliff, while an abridged version is like a gentle slope, but we could see the same scenery at the hilltop.

The scholars engaged in academic research and foreign readers who understand traditional Chinese culture could read a complete translation that best reflects the original text. However, this would limit the book’s accessibility. For the average reader, the abridged version might be easier to grasp, he said.

Liu Shicong, a professor at Nankai University and an expert on the English translation of Dream of the Red Chamber, called Lin’s version “bold and wise.” Its annotation and rewriting of the content will be an inspiration for future translators of the book.

Hou Li is a reporter at the Chinese Social Sciences Today.