Japan defeated in broadcast battle for Manchukuo

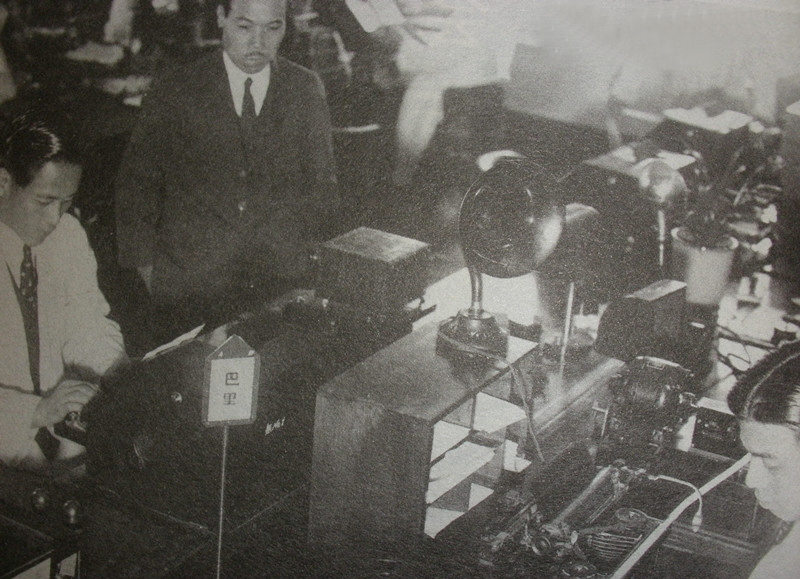

Japanese work at the Manchuria Telephone and Telegraphy Company (MTT).

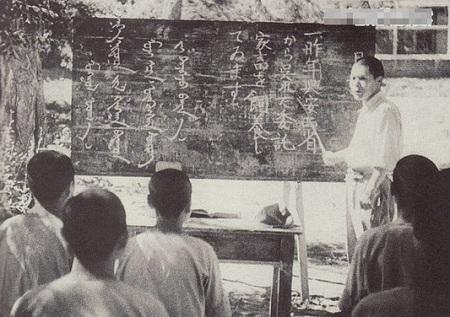

Students in Northeast China are taught in Manchu and Japanese during the Manchukuo period (1932-45).

Following the 1931 Mukden Incident, also known as the September 18th Incident or Manchurian Incident, Japan colonized Northeast China and established the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932. To assert its ideological control over the region, Japan broadcast propaganda-rich programs and newscasts over the radio.

Radio was considered an effective medium for Japan’s propaganda efforts on account of its wide transmission range, fast speed, sharp audience penetration and low operational costs. However, its cultural and political influence was minimal over Chinese listeners in the region for various reasons.

Rise and fall

Japan’s on-air offensive in Northeast China spanned 20 years, from the 1925 establishment of its broadcast center in Dalian, Liaoning Province, to Tokyo’s World War II surrender in 1945. This two-decade period can roughly be divided into three stages.

The first stage spanned from 1925 to 1933, when Japan gradually asserted its dominance over China. During this period, Japan made no secret of its radio propaganda ambitions in Manchukuo, declaring a “radio war” against rival countries, the Kuomintang government and the Soviet Union.

The second stage, from 1934 to 1938, saw Japan step up propaganda efforts and tighten its broadcast control in Northeast China, when radio penetrated all corners of Manchukuo, making the region a fortress for Japan’s broadcasting aggression in China.

The third stage, from 1938 to 1945, was characterized by Japan’s propaganda decline, with efforts all but ceasing after 1942. On August 15, 1945, Japan’s unconditional surrender was broadcast over the radio. Four days later, Soviet forces took over radio stations in the region and effectively ended Japan’s on-air presence.

Propaganda in programming

During the Manchukuo period, Japan sought to strengthen Chinese northeasterners’ identity under colonial rule through entertainment, education programs and pro-colonial news reports.

Entertainment programs were the main form of Japanese colonial propaganda. With the strongest appeal among audiences, music, traditional Chinese opera and radio dramas became key fronts in the “war of ideas.”

Therefore, the Japanese government, Manchukuo administration, South Manchuria Railways Company and Japan Broadcasting Corporation jointly founded the Manchuria Telephone and Telegraph Company (MTT) in August 1933.

As a mouthpiece for Japanese authorities, the MTT arranged a number of entertainment programs for audiences to propagate the legitimacy of Japan’s occupation of Northeast China.

Meanwhile, Japan surveyed listeners in a bid to broaden the appeal of its radio programs based on people’s habits and interests. Entertainment art forms, including traditional Chinese opera and xiangsheng (cross-talk), were found to be most appealing to Chinese audiences.

During the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, entertainment programs were essential to Japan’s ideological control. In practice, ideas including “concord between Japan and Manchukuo” and the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” was infused into programming.

Reaching the masses

Following the establishment of the MTT, Japanese propagandists stepped up efforts to popularize radios across Northeast China, thereby expanding their audience and broadcasting scope.

Besides the major cities of Dalian, Mukden (modern-day Shenyang, Liaoning Province) and Harbin, Heilongjiang Province, radios were also sold at telegraph bureaus in Jilin City and Yanji, Jilin Province; Mudanjiang, Fujin and Qiqihar, Heilongjiang Province, and Chengde, Rehe Province (modern-day Hebei Province).

Through its direct-sales model, the MTT successfully reduced costs and monopolized radio sales. Japanese authorities also held large-scale exhibitions and installed radio booths to teach Chinese people how to operate radios.

Chinese were encouraged to buy radios under payment plans and radio-service fees were lowered to drive sales. Radio owners who fell behind on payments were not punished, because propaganda broadcasts formed a key part of the “national strategy” and radio ownership was essential to achieving this goal.

Cultural objectives

It became mandatory for Chinese to learn Japanese and foster “Manchukuo culture” during the puppet state’s existence. Broadcast during prime time, Japanese education programs aimed to make Japanese the common language in Greater East Asia.

Broadcasting was the most common means for Japanese-language education at schools. The language was even taught with “relevant programs as immediate teaching materials.” Due to these programs, Japanese became one of the universal languages in Manchukuo.

Japanese colonists attempted to develop a Manchukuo culture that differed from the Chinese civilization. Incorporating rich “Manchukuo elements” into broadcasts, they aimed to sever or distort internal relations between the culture of Northeast China and the broader Chinese context, thereby fostering a Japanese colonial cultural identity among Chinese.

Uniting the colonies

A total of 25 radio stations operated across Manchukuo between 1925 and 1945. Radio helped Japan maintain its control over Northeast China, providing real-time surveillance of society and people in the region.

Radio linked Japan, Manchukuo, the Wang Jingwei (1883-1944) puppet regime, the North China puppet regime and colonies, including Korea and Taiwan. In the colonies, the radio gave the Japanese a strong social status, “placing them in a dreamland that made them feel at home.”

Reflecting on the influence of radio, a Japanese colonist said: “I can hear the radio almost everywhere, in shops, restaurants…when people dress in kimono, eat Japanese food and listen to Japanese-language news and music, I don’t feel [far] from my motherland in Manchukuo.”

Japan went to great lengths to create the illusion of China-Japan friendliness and Japanese prosperity. Radio broadcasts were made of Chinese children offering Spring Festival blessings in Japanese and Japanese Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka’s (1880-1946) speech declaring the signing of the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact on the Chinese Eastern Railroad was broadcast live. Japanese colonists felt a great sense of pride and belonging, with radio broadcasts countering loneliness and reinforcing their sense of patriotism.

Cold reception with Chinese

According to Japanese documents, however, radio propaganda had little influence over Chinese ideologically. Radios were accessible only to Japanese nationals and Manchu elites. Due to Japan’s colonial rule and exploitation, most Chinese were too poor to buy radios, even under payment plans.

Japanese statistics indicate that Chinese listeners accounted for, at most, 5 percent of the Manchukuo radio audience. Furthermore, Chinese households accounted for less than 1 percent of radio owners in Northeast China.

The radio aimed to educate Chinese about Japan through Japanese-language broadcasts. However, favoring Chinese-language broadcasts of entertainment programs, Chinese listeners tended to shun programs aired in Japanese.

Japanese colonists employed various strategies to shape Chinese northeasterners’ national consciousness and encourage them to embrace Japan’s colonial occupation by identifying with its political and cultural rule. However, their unjustified aggression and the resistance of Chinese northeasterners’ inherent national consciousness thwarted radio propaganda efforts and led to eventual failure along with Japan’s military breakdown.

Qi Hui is a research fellow from the School of Journalism and Communication at Chongqing University.