Balancing approach to Chinese political thought

Gu Yanwu

Huang Zongxi

Wang Fuzhi

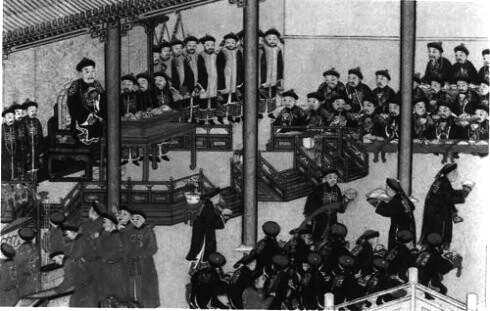

Emperor and court officials are major political actors of the “Royalty Doctrine.”

The history of Chinese political thought has been a full-fledged independent field since the 1920s. At the current stage, the subject is listed as a compulsory course for every student of politics and public administration.

Moreover, a substantial number of papers are dedicated to the subject and the topic accounts for a considerable share of the content in prestigious academic publications, such as the Journal of Political Science and History of Political Thought. Nonetheless, studies on the history of Chinese political thoughts have been severely hindered by disagreements over its standing among all disciplines in humanities and social sciences.

There are two approaches to the subject. On one hand, it is categorized as a branch of Chinese intellectual history and juxtaposed with studies on ancient economic and legal thought. On the other hand, it is classified as subordinate to political sciences and assigned an equal footing with studies on the history of Western political theories.

The task of historians is to reveal truth of the past mainly through textual research. Yet political scientists are primarily concerned with decoding the inner logic of political development. In the domestic context, they are expected to illuminate the evolution of Chinese political thought. Generally speaking, the latter put more emphasis on the diversity of perspectives and theories concerning political development.

‘Royalty Doctrine’

Liu Zehua, a professor of history at Nankai University, once proposed that the evolution of “Royalty Doctrine” is central to the unfolding of Chinese political thought. Such a proposition is undoubtedly true with regard to pre-modern China. However, “Royalty Doctrine” has been challenged in at least three ways since the late Qing Dynasty.

The first challenge came from Western ideas of freedom, democracy and equality. At the same time, scientific thought undermined the semi-divine aura of kingship and the notion of the Mandate of Heaven. Soon after, Marxism revolutionized the entire traditional social order.

In addition, Western influences broke apart clan organization and patriarchy, the underlying infrastructure of the monarchy. For these reasons, monarchy ceased to exist in Chinese society after the abdication of Emperor Puyi (1906-67) in 1912. Consequently, “Royalty Doctrine” lost its life line and prestige. Unfortunately, there is no satisfactory account for the modern development of domestic political thought.

Generally speaking, Chinese political ideas advanced in step with the progress of history. However, there were several regressive movements. For example, pre-Qin (2100-221 BC)thinkers had a more profound interpretation of “Royalty Doctrine” compared to scholars of the Han Dynasty (206 BC- AD 220).

The concept of “Heaven” became mired in mysticism after the pre-Qin era. Another example is the late Ming Dynasty, which espoused enlightenment ideas that were far more progressive than the political ideas of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). We can also learn a lot from political thinkers and authors who were active during the Republican period (1912-49).

How can one understand the back and forth in the course of intellectual history? What are the causes? Is there any underlying rule? By contemplating these questions, we can not only gain a deeper insight into ancient political ideas but also envision a brighter future for contemporary studies of political thought.

Heads in the sand

Though it is an indispensible component of domestic studies on political sciences, the history of Chinese political thought has been marginalized for various reasons. For example, concepts and terminologies of political science are not readily applicable to the subject. A more serious problem is that research in the field so often adopts a head-in-the-sand approach to evade reality.

To be more specific, research on ancient political ideas seems pedantic, appears to lack social concern and is perceived as having little contemporary relevance. Moreover, scholars have attached too much importance to ancient thought, while the modern and contemporary eras remained underexplored.

To be honest, most studies on the political thought of the People’s Republic of China are devoid of substance and solely aimed at echoing the dominant voice of the moment. Furthermore, little attention has been paid to pressing issues that have emerged in tandem with modernization, such as moral confusion and civic education. Scholars of the field are supposed to address these issues with their expertise.

Overlooking historical dimension

Most research on the subject is preoccupied with content and logical analysis of political ideas, while historical inquiry that would illuminate the origins of certain ideas is neglected. As far as I am concerned, there should be a further integration of historical and ideological analyses. To be clear, scholars need to clarify the origins, evolution and backgrounds of political ideas in order to specify the positions and statuses of certain figures and theories.

Studies of the field might go awry without such scrutiny. For instance, some scholars claimed that the political inclinations of Gu Yanwu (1613-82), Huang Zongxi (1610-95), Wang Fuzhi (1619-92), known as the Three Great Literati of the Late Ming Dynasty, were analogous to the ideas of the European Enlightenment.

They went on asserting that the nascent capitalist ideology evident in the late Ming Dynasty could have reached maturity if dynastic continuity had been sustained. However, had they paid heed to the historical dimension of political ideas, they would have known that the late Ming zeitgeist was largely a revival of pre-Qin thought rather than a full-fledged revolutionary movement in its own right, and thus they would be more cautious when making such assertions.

There is another example attesting to the importance of the historical dimension of political thought. Many years ago, Liu asked a doctoral candidate from the department of philosophy to give a detailed explanation of the historical significance of ren, meaning “benevolence,” in his dissertation defense. The candidate was caught off-guard.

The implication of Liu’s question is crystal-clear: the philosophical significance of ren was deeply rooted in its historical context. Without an adequate knowledge of its context, scholars might exaggerate the influence of certain ideas and intellectual currents.

For instance, when scholar-officials of the late Eastern Han Dynasty expressed criticism of corrupted potentates, they were not on their own. Instead, their protégés, acquaintances, clans and students at the imperial college were there to support their cause. In this vein, researchers should not give too much credit to the spiritual strengths of these scholar-officials. Similar logic can also be applied to Donglin Movement of the late Ming Dynasty.

Limitations

Studies on the history of Chinese political ideas also suffer from outdated theories and methodologies. Since the implementation of the Reform and Opening-up Policy in 1978, most Chinese academics have abandoned rigid theoretical frameworks, such as class analysis and the dichotomy between idealism and materialism.

However, the theoretical basis of the subject remained flimsy because researchers were unable to forge a consensus on the applicability of relevant analytical tools. In addition, they were misguided by various concepts and terminologies that have little if anything to do with present and past realities.

Without workable theories and diverse perspectives, the field will remain stagnant. For example, some scholars spend a lot of time clarifying the differences between people-oriented thoughts and democracy but turn a deaf ear to contemporary voices on the evolution of democratic ideology. Without a sound grasp of Western political theories, an impartial clarification is hardly possible.

To overcome methodological drawbacks, researchers need to pay more attention to literary records rather than solely focus on official manuscripts and biographies of the past at the first place. The renowned historian Chen Yinque (1890-1969) worked out a series of influential conclusions through integrated research on literary and official records.

Second, most researchers are preoccupied with the contents of historical records yet are negligent of their forms. For example, they explain in detail what was said in imperial edicts and ministerial reports but seldom think about the political implication of how messages were conveyed in various forms of official documents. Finally, researchers of the field need to conduct more oral interviews and quantitative studies, which are particularly important for exploring modern ideas and thinkers.

Ji Naili is a professor of politics at Nankai University.