Geography played large role in pushing ethnic groups south

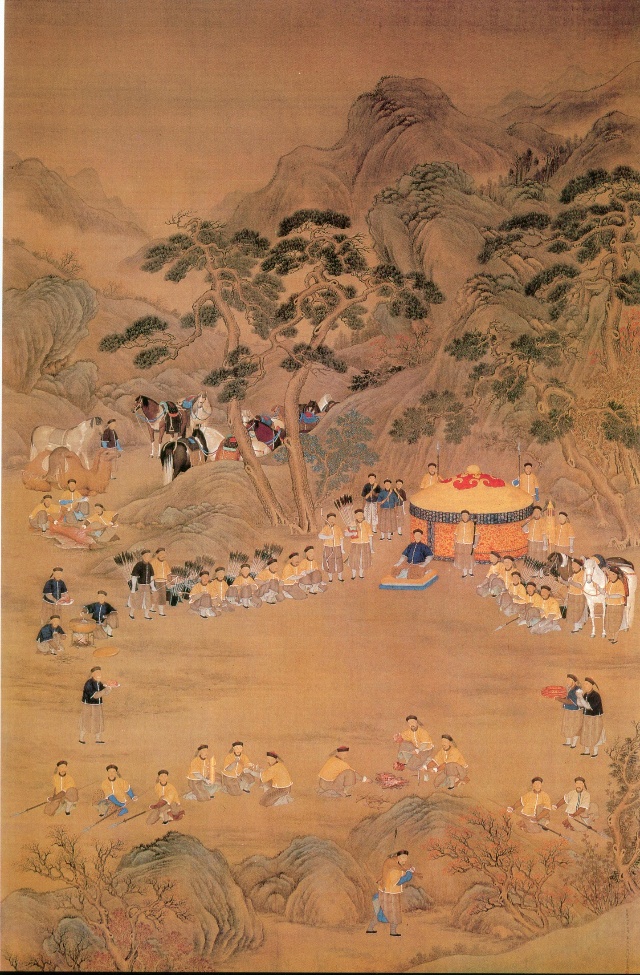

Manchu rulers first established a regime in Northeast China in 1616. Upon defeating the Ming empire, they settled in the former Ming capital of Beijing in 1644. Pictured here is Qianlong Emperor in an imperial hunt used as an exercise to train troops in the traditional martial skills of archery and horsemanship.

Through the study of ancient Chinese history, in particular ethnic history and the history of ethnic relations, historians have discovered an interesting phenomenon. Ethnic groups in Northeast China and Northeast Asia after the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) showed a tendency to migrate southward into the Central Plain (Zhongyuan) as they grew and expanded.

In the Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern dynasties (220-581), Xianbei tribes departed from the region that is now Liaoning Province to Hebei Province and then into the Central Plain, while Tuoba tribes traveled first to the grasslands in the west and then to the south, which was dominated by the Han Chinese. Qidan and Nüzhen (Jurchen) tribes in the Song, Liao and Jin dynasties (960-1234) embarked on the same route. Why was southward migration a trend in ancient times?

Geography, social organization

In terms of ecological environment, forests and rivers cover the northern part of Northeast China, and the western part is a mix of low hills and grasslands, while the broad plains in the south are good for growing crops.

These conditions—especially in the northern and western regions—were suitable for sustaining only small tribes or tribal confederations of nomads who relied on hunting as their major source of production. In contrast, social groups in the south were more capable of developing further into larger, advanced communities. Most political bodies, such as kingdoms, originated from plains where people could grow crops and settle into permanent villages. This theory can also explain why ethnic groups in Northeast China primarily established regimes in the south.

However, a prerequisite for this explanation is that ethnic tribes in the north must have first attempted to overcome environmental constraints. The exploration of surrounding regions was only made possible when a tribe’s internal development and expansion reached the limit of local social conditions. The narrow space in the north was far from sufficient, so the southern region had greater potential to become a magnet for tribes from the north.

The vast landscape in Northeast Asia was home to a number of tribes that existed in various stages of development. The earlier a tribe took shape, the more confined it was to the northern region. At least, tribal forces were mostly involved in communications and interactions within the region before the Wei and Jin dynasties (220-420). Afterward, ethnic tribes migrated to the south, causing a ripple effect among southern groups.

It can be said that the intensive contacts among ethnic tribes drove political bodies in Northeast China to move southward. Within the region, the cumulative development of farming in the south led to sustainable economic growth, accelerating the development of clans and tribes into higher forms of political organization.

Correspondingly, fishing, hunting and nomadic lifestyles in the north were rather simple and repetitive, so modes of production were slow to change. Meanwhile, nomadic forces mainly concentrated in the region west of modern Liaoning Province and east of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region formed regimes in the hunter-gatherer phase that found room for further development in the western grassland. The agrarian region in the south was large, highly attractive and capable of supporting political development in Northeast China, which ultimately allowed ethnic tribes to grow bigger and stronger.

Though the southern part of Northeast China was a cradle for relatively developed political bodies, they were all regional. Northeast China lacked the economic support for the survival and establishment of a huge kingdom. It also lacked attractiveness in terms of culture. In fact, not only Northeast China but also Northeast Asia as a whole in ancient times had no “capital of culture” to draw others into the region.

Similar political entity

The overall strength of Central Plain civilization was largely attributed to the southward migration of tribal forces in Northeast China. In the eastern sphere of the Eurasian Continent, two distinct political entities coexisted, namely the nomadic empire in the northern pastures and an imperial empire dependent on agricultural production in the south.

Large-scale peasant culture and nomadic culture only appeared in the eastern sphere because vast grasslands and farm lands were conducive to material and cultural accumulation, which to some extent constitutes the key characteristics of the two great civilizations on the continent.

Recent studies tend to show that the emergence of nomadic empires in the north was actually a strategic response to the northward expansion of the Chinese empires. This theory is supported by the fact that the Xiongnu empire was established later than the Chinese imperial states in the Xia, Shang, Zhou, Qin and Han dynasties (2070 BC-AD 220).

The living environment and political structure in these two empires were quite different, but they both were equipped with characteristics of core areas, thus making them attractive to people in the surrounding regions. Northeast China and Northeast Asia were stuck in between these two empires, and southward migration was the result of the strong driving force between Chinese peasant culture in the Central Plain and the nomadic culture in the grassland.

Tribal forces in the northeast were able to move westward into the pastures and grow into a nomadic empire. They were also able to move southward into the Central Plain and transform into an imperial state that relied on agricultural production. There were many reasons for the choices they made at that time, but historians can be certain that the primary motivations were lifestyles and the early forms of political organization that they inherited.

As this article has already illustrated, the political evolution indicated that the more advanced political bodies were mainly in the southern plains where people grew crops as major sources of production. When they attempted to break the boundary and expanded, the similar peasant culture in the Central Plain was more attractive than the nomadic culture. Meanwhile, the western part of Northeast China, where hunter-gatherer forms of production dominated, people showed more interest in the nomadic empires.

Though political organization might have stood at various stages of development, the attraction among similar political entities was much stronger than that between different entities.

Dualistic structure

The process of interdependence and conflict between the core and peripheral areas defined the regional structure of Chinese civilization. Core area refers to the native territory that was known for irrigated agriculture, namely the Yellow River and the Yangtze River.

In the course of historical development, many political forces were widely distributed here and eventually established the early dynasties, such as the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties (2070-256 BC). A dualistic structure began to take shape between these relatively advanced forms of political organization and a periphery composed of the tribal forces that formed under the pressure of various geographical conditions in the fringe areas.

Within the framework, core areas were relatively stable, while peripheral areas were rather volatile. The political, economic, military and cultural interactions between two realms, in particular the dominant position of empires in the Central Plain, decided the stability of the structure. When the Central Empires were more powerful, peripheral areas were more likely to be subjugated. Otherwise, the Central Empires might lose control in the fringe areas.

The attractiveness of the core area continued to rise as the Central Empires remained prosperous and incorporated the neighboring tribes, while the interaction with the nomadic empires that overlapped with the core area of the Central Plain also boosted its reputation.

The means of subsistence of people in the Central Plain and the grasslands were significantly different. Despite the fact that the mighty federation of nomad tribes was founded in response to the pressure from the Central Empires, the development and evolution of political entities in the core area of nomadic civilization remained vital, leading to more than 2,000 years of confrontation.

Sitting on the edge of the two realms, Northeast China absorbed the best elements from both sides. Once it had the capacity to expand its territory, it acted without hesitation.

In addition to achieving political maturity on the solid basis of agricultural production in the south, the nomadic empire lost its characteristics as it also began moving southward, which in turn reinforced the attractiveness of the Central Plain. Thus, in times of instability of the Central Empires, the tribal forces in the northeast took the chance and occupied the region. With or without fortified walls, the fate of Central Empires was sealed.

In conclusion, regional constraints and the structural driving forces of the Central Plain were the internal and external factors that motivated the southward migration of ethnic tribes in Northeast China.

Li Hongbin is a professor from the School of History and Culture at Minzu University of China.