Contemporary Chinese ecological literature reengages classical ecological thought

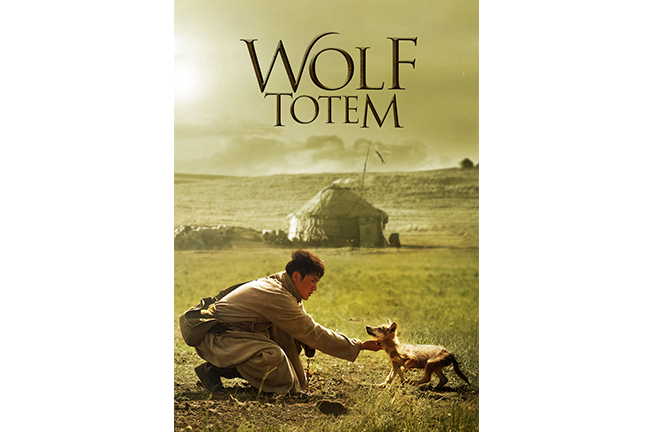

FILE PHOTO: A poster of the movie Wolf Totem, adapted from Jiang Rong’s novel of the same name, a best-selling work in China that narrates the spiritual journey of a Beijing intellectual into the world of the nomadic Mongols, witnessing a culture that highly honors the balance between humanity and nature

Environmental degradation has become a stark reality of modern life. While reaping the conveniences of industrialization, urbanization, and technological advancement, humanity is simultaneously grappling with an ecological crisis. In the Chinese context, revisiting classical ecological philosophies and reactivating their latent potential within a postmodern framework represents both a conscious act of cultural inheritance and a proactive response to contemporary environmental challenges.

Numerous scholars—including Ji Xianlin, Zhang Shiying, Meng Peiyuan, She Zhengrong, Feng Tianyu, Lu Shuyuan, Zeng Fanren, and Chen Yan—have produced seminal academic works illuminating the ecological insights embedded in classical Chinese thought. Similarly, many contemporary Chinese writers, particularly those contributing to the burgeoning field of ecological literature, have returned to these intellectual roots in search of pathways to address today’s ecological crisis. Contemporary Chinese ecological literary works exhibit distinctly localized characteristics, offering a meaningful contrast to ecological literature emerging from other parts of the world.

Confucian ecological thought

At the heart of Confucian ecological wisdom lies an organic, teleological worldview grounded in the unity of humanity and nature, as expressed in classical texts such as the Book of Changes: “The great virtue of Heaven and Earth is called life” and “Production and reproduction is what is called (the process of) change.” This vision is further articulated through values such as benevolence toward people and compassion for all living things, participation in and assistance with the natural processes of creation and transformation, the view of all people as kin and all creatures as companions, the unity of all beings, and the principles of moderation in consumption and timely restraint.

Contemporary ecological writers often approach environmental reflection through a Confucian lens, driven by the moral responsibility and deep concern characteristic of the Confucian intellectual tradition. Writers such as Xu Gang, Zhe Fu, Li Qingsong, and Li Cunbao exemplify this ethos. Xu Gang, for instance, transforms his heightened awareness of adversity into an urgent concern for ecological well-being in works such as Woodcutter, Wake Up!, Guardian Spirit, and A Biography of the Earth, all of which passionately call for the protection of nature and highlight the dangers of an escalating ecological crisis.

Contemporary ecological authors also construct literary figures modeled on Confucian virtues. In Shen Rong’s novel Dead River, the protagonist Jin Tao is an upright government official who recognizes that economic development must not come at the expense of environmental integrity. Similarly, in Hu Fayun’s novella The Disappearance of Lao Hai, a journalist sacrifices his life to protect endangered Francois’ leaf monkeys in the mountains of western Hubei Province, thwarting the threats posed by tourism development and poaching, and embodying Confucian compassion for all beings. Zhao Defa’s novel Anthropocene portrays Professor Jiao Shi, a geologist who promotes ecological awareness and the concept of the Anthropocene while investigating the environmental impact of foreign waste—presented as a modern-day Confucian ecological enlightener.

With the steady advancement of ecological civilization in China, many ecological writers intentionally align the vision of “Lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets” and the notion of “a community of life for humanity and nature” with Confucian ecological wisdom, weaving powerful environmental narratives.

Taoist ecological wisdom and literary expression

Chinese Taoist ecological philosophy presents a more profound, non-anthropocentric ecology that emphasizes the organic interrelation of all things: “Tao gave birth to the One, the One gave birth successively two things, three things, up to ten thousand.” Central principles such as the recognition of the equal value of all things, non-interference with nature, and moderation in desires advocate a harmonious, poetic mode of dwelling within the natural world. This vision is poetically rendered in the ideals of Laozi, Zhuangzi, and Tao Yuanming’s The Peach Blossom Land.

The banyan tree in The Tree I Took Shelter Under by Yu Jian becomes an almost emblematic image of the Tao, symbolizing the natural world itself. Yu’s works—Naming a Crow, The Gray Squirrel, and In Praise of the Seagull—follow the Taoist idea of “cleansing away the most mysterious sights of one’s imagination,” seeking to strip away cultural embellishments and reveal the innate character of natural beings.

Zhang Wei similarly embraces Taoist values in his writing. His essay Merging with the Wild articulates a vision of coexistence with nature, and the “emotional bond with nature” he often invokes a Taoist ecological sensibility inclined toward retreat into the natural world. The life depicted in the seaside village of his novel September Fable represents an ideal Taoist vision of harmony between humanity and nature.

Characters in Chi Zijian’s novels often reflect Taoist archetypes— “The singular man departs from the normal value system, but matches the principles of Heaven.” Figures such as Baozhui in Fog, Moon, and the Cattle Pen, Chen Sheng in Green Noon, and An Xue’er in Atop the Mountains all exemplify this sensibility.

Other authors, including Liu Liangcheng and Han Shaogong, also reflect Taoist ideals of tranquil cohabitation with nature in their writings. Liu’s essay collection A Village of One offers poetic depictions of agricultural life on the edge of the Gobi Desert in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, resonating with Taoist ethos that espouses the equality of life and death and the parity of all beings. Through such expressions, Taoist ecological wisdom infuses contemporary literature with a refreshing vitality that transcends the mundane.

Buddhist ecological perspectives in literary practice

Buddhist ecological consciousness is rooted in the doctrines of dependent origination and emptiness, the Middle Way, and selflessness leading to nirvana. It upholds a holistic belief in the interconnectedness of all things and the equality of all life forms, transcending egocentrism and anthropocentrism while affirming nature’s emotional resonance and inherent value.

Ecological poet Chen Xianfa draws upon Buddhist teachings to explore ecological interconnectedness in poems such as “Elegy for Parting,” where birds, frogs, fish, and pine trees are portrayed as humanity’s spiritual kin, illustrating the intimate friendship among all beings. Zang Haiying’s poem “Westward Journey” conveys that those who perish along the westward path find solace in the presence of birdsong at the moment of death and experience benevolence in the knowledge that their bodies may provide sustenance for insects and ants—an articulation of the consolatory dimension of Buddhist ecological wisdom in confronting mortality. Chen He’s poems “Poem of Fate,” “Beginning of Winter,” and “Record of the Ants” honor the Buddhist ethic of refraining from killing and cherishing life.

Jia Pingwa’s novel In Memory of Wolves advances a Buddhist vision of ecological equality, emphasizing that wolves, like humans, are essential links within the food chain. In The Hunters’ Plain, Xue Mo portrays ecological collapse resulting from overgrazing, critiquing unchecked human desire through a Buddhist lens. Buddhist monks and nuns often appear in ecological literature as symbols of environmental guardianship, conveying ideals of compassion and purity.

The ecological perspectives of China’s ethnic minorities also belong to the broader corpus of classical Chinese ecological wisdom. Many of these cultures uphold animistic worldviews, a deep respect for nature, and a reverence for life. Influenced by such beliefs, ethnic minority authors have produced a significant body of ecological literature. For instance, the Evenk writer Ureltu, Mongolian writer Guo Xuebo, Manchu writers Hu Donglin and Ye Guangqin, Tibetan writers Alai and Long Renqing, Yi writers Jidi Majia and Luowu Laqie, Pumi writer Luruodiji, Bai writers Zhang Chang and He Yongfei, Hani writers Langque and Cun Wenxue, Gelao writer Zhao Jianping, Hui writers Shi Shuqing and Li Jinxiang, and Tujia writers Ye Mei and Li Chuanfeng, among others, have integrated these beliefs into their writing.

In Alai’s The Mushroom Circle, the protagonist Si Jiong embodies animistic beliefs and the principle of the equality of all life. Works by Han Chinese authors, such as Jiang Rong’s Wolf Totem, Chi Zijian’s The Last Quarter of the Moon, Li Juan’s Winter Pasture, and Ai Ping’s Listening to the Grasslands, have also meaningfully engaged with the ecological wisdom of ethnic minorities. Together, these works enrich Chinese ecological literature with distinctive ethnic and regional textures.

Classical Chinese ecological wisdom has profoundly influenced the evolution of contemporary ecological literature. This intellectual revival has deepened writers’ engagement with traditional culture and inspired them to draw from both refined traditional Chinese culture and folk sources to address urgent modern challenges. However, it is important to recognize that classical ecological wisdom remains an intuitive, premodern form of understanding. It must be integrated with modern rationality to advance toward a more comprehensive ecological framework.

Such synthesis is already evident in works like Guo Xuebo’s novella Buried in the Sand, where a lama and a desert-research scientist work side by side, or Duan Kunlun’s play Green Harmony, where a Buddhist monk collaborates with a biologist. These examples illustrate how classical wisdom and modern ecology can collaborate.

As the Book of Rites states: “All things are nourished together without injuring one another. The courses of the seasons, and of the sun and moon, are pursued without any collision among them.” The fusion of classical ecological philosophy, folk ecological awareness, and contemporary ecological science offers a rich spiritual foundation for Chinese ecological literature and contributes valuable insights to the broader pursuit of ecological civilization.

Wang Shudong is a professor from the School of Chinese Language and Literature at Wuhan University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG