Through mists of time, image of ancient China comes into focus

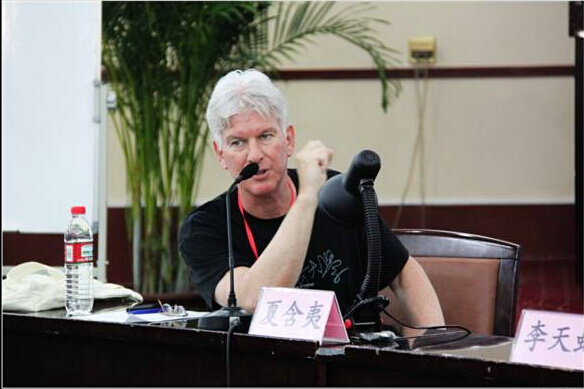

Edward Shaughnessy

Edward Louis Shaughnessy, the distinguished service professor in Early Chinese Studies of the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago, is a noted Sinologist and has served as the editor-in-chief of Ancient China. His interests include the cultural history of the Western Zhou and Warring States period, paleography and the I Ching. His representative works include Rewriting Early Chinese Texts and Arousals and Images: Essays on Ancient Chinese Cultural History.

Starting in the 1920s and 1930s, Chinese academia began suspecting the validity of ancient Chinese historical texts. But due to the excavation of a large amount of materials, this trend has gradually declined. CSST’s reporter sat down with Shaughnessy (Chinese name Xia Hanyi) to learn his views on the studies of ancient Chinese history.

CSST: How to put things in chronological order is an inevitable problem when studying on ancient Chinese history. You have confirmed the dates for the span of the Western Zhou Dynasty and what are the implications of chronology for the study of ancient Chinese history?

Edward Shaughnessy: Historians always consider dates to be important. Without knowing the sequence of historical events, it is difficult to understand the evolution of history. As for the study of ancient Chinese history, the knowledge of the general sequence of historical events has already met the basic demands of historical study. Thus, not every scholar has to spend several years studying the issues of chronology, such as the date when King Wu of Zhou conquered the Shang Dynasty. For example, we roughly agreed that scholars should find out whether Wu’s conquest of the Shang happened in 1122 B.C. or 1046 B.C. because it answers the question of whether the Western Zhou Dynasty continued for 351 years or 275 years. But for most people, it is not significant to know whether the specific date of Wu’s conquest was 1046 B.C. or 1045 B.C. Even so, scholars who study chronology still know that the date is consistently within a frame of time. A miss is as good as a mile and it is worth studying the problem in detail. This is also recognized by Chinese academia.

CSST: There is a view that Sinology is trending toward the Oriental. How do you evaluate this viewpoint?

Edward Shaughnessy: Whether one is speaking of the study of ancient Chinese civilization, Sinology or Chinese studies, the research object is China, most research data and researchers are in China and the majority of the research paradigm is created by Chinese scholars. So to speak, China’s native scholars are maturing and their achievements are plentiful. But foreign scholars have their own unique perspectives on issues of Chinese social sciences and they will make additional contributions to the study.

CSST: You wrote the article Historical Perspectives on the Introduction of the Chariot into China by combining findings from archeological sites and historical materials to demonstrate the Shang and Zhou chariots’ military use and their functions in the changes of later dynasties. So how should we combine archeological materials and document literature effectively when studying ancient Chinese history?

Edward Shaughnessy: The issue of chariots was one of my early research topics. At that time I had studied the military history of the Western Zhou Dynasty because it is the key to understanding the Western Zhou bronze artifacts. When studying military history, one will inevitably meet with the issue of chariots and should be concerned about archaeological evidence. Then that’s why the article Historical Perspectives on the Introduction of the Chariot into China was written.

Basically, foreign academia has already made a final conclusion and pointed out that the birthplace of chariots was the Caucasus region, and they then spread to the West, Mesopotamia, and reached to China through the eastern route. During the course of transmission, the shape and structure of chariots underwent slight changes. At present, quite a few Chinese scholars have recognized that chariots originated from West Asia. Of course, some Chinese scholars have argued that Chinese chariots are distinguished from Mesopotamian chariots, so Chinese chariots are “unique.” From my point of view, Chinese chariots and Mesopotamian chariots are extremely similar. So we cannot simply point out the differences between Chinese chariots and Mesopotamian chariots to argue for the uniqueness of Chinese chariots.

Chinese scholars really hope to promote Chinese culture, but there never existed a ranking from best to worst among different cultures. These days, common people in China are willing to use the latest international products, which is similar to South China peasants in the late Ming Dynasty who rapidly accepted Western crops. In the capital of the Tang Dynasty, people from the continents of Europe and Asia lived together and exerted a significant influence on local customs. So this absorption and inclusiveness have always existed in Chinese culture without exception in earlier times. At present, the Chinese government provides various projects for young scholars to go abroad and have a visit. These are very precious opportunities because scholars can conclude whether this is a unique or common character when experiencing other different cultures.

CSST: Currently, the trend among members of Western academia is to doubt the reliability of ancient sources when formulating a picture of ancient Chinese history. So would you please expand upon the view of Western academia toward Chinese ancient history?

Edward Shaughnessy: Beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, most Western scholars, to a certain degree, started taking a skeptical attitude toward the credibility of traditional Chinese history and documents, which is parallel to the prevailing suspicion of ancient documents in China. However, since the 1970s, an amount of excavated documents has been successively discovered, prompting the realization that this school of thought may have been excessive in its doubts. Hence, at present, a general belief in the ancient sources has emerged in China. Abroad, quite a few scholars are willing to read these real ancient documents, but I’m afraid very few people would say they believe in their veracity. Suspicion is a fundamental attitude for scholars doing research.

This is more than an issue of the ideological trend, and it involves some certain issues. For instance, the Book of Rites belongs to Confucian classics and is one of the most significant documents in the ancient history of China as well. However, it was said that the Book of Rites was compiled by people in the Han Dynasty and many articles were contrived by them. But the traditional opinion is that the texts of Fangji, the Doctrine of the Mean, Biaoji and Ziyi were attributed to Zisi, grandson of Confucius. But since the 1930s, some people started to suspect that these four articles were made by people in the Qin and Han Dynasties. That was until the late 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, when copies of Ziyi were found on Guodian bamboo slips and Shangbo bamboo slips of Chu, demonstrating that Ziyi wasn’t written in the Qin and Han Dynasties. Many people think that this finding can overcome suspicion of the ancient sources and in turn support their validity. I agreed with the former, but it doesn’t mean it would demonstrate the validity of the ancient sources. The “ancient” is equivalent to Ziyi in the Book of Rites, but Ziyi in the Book of Rites is not only different from Ziyi in the Guodian bamboo slips and Shangbo bamboo slips of Chu in terms of order but also content. If these two are regarded as the same article, then there is nothing wrong with it. But it is fine to treat these two as independent articles. Ziyi in bamboo slips of Chu definitely reflects the history of compilers in the Han Dynasty. In addition to Ziyi, many excavated documents are slightly distinguished from handed-down documents. It seems that in the face of a half glass of water, people who believe in the ancient said the glass is half full, but people who suspect the ancient said the glass is half empty or the opposite. On account of a different point of view between these two ideological trends, their conclusions are totally distinctive.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 626, July 28, 2014

Translated by Zhang Mengying

The Chinese link: http://sscp.cssn.cn/zdtj/201407/t20140728_1269146.html