Recognition: new paradigm for law studies

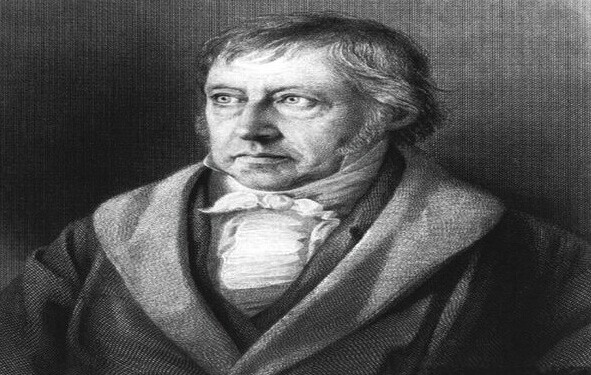

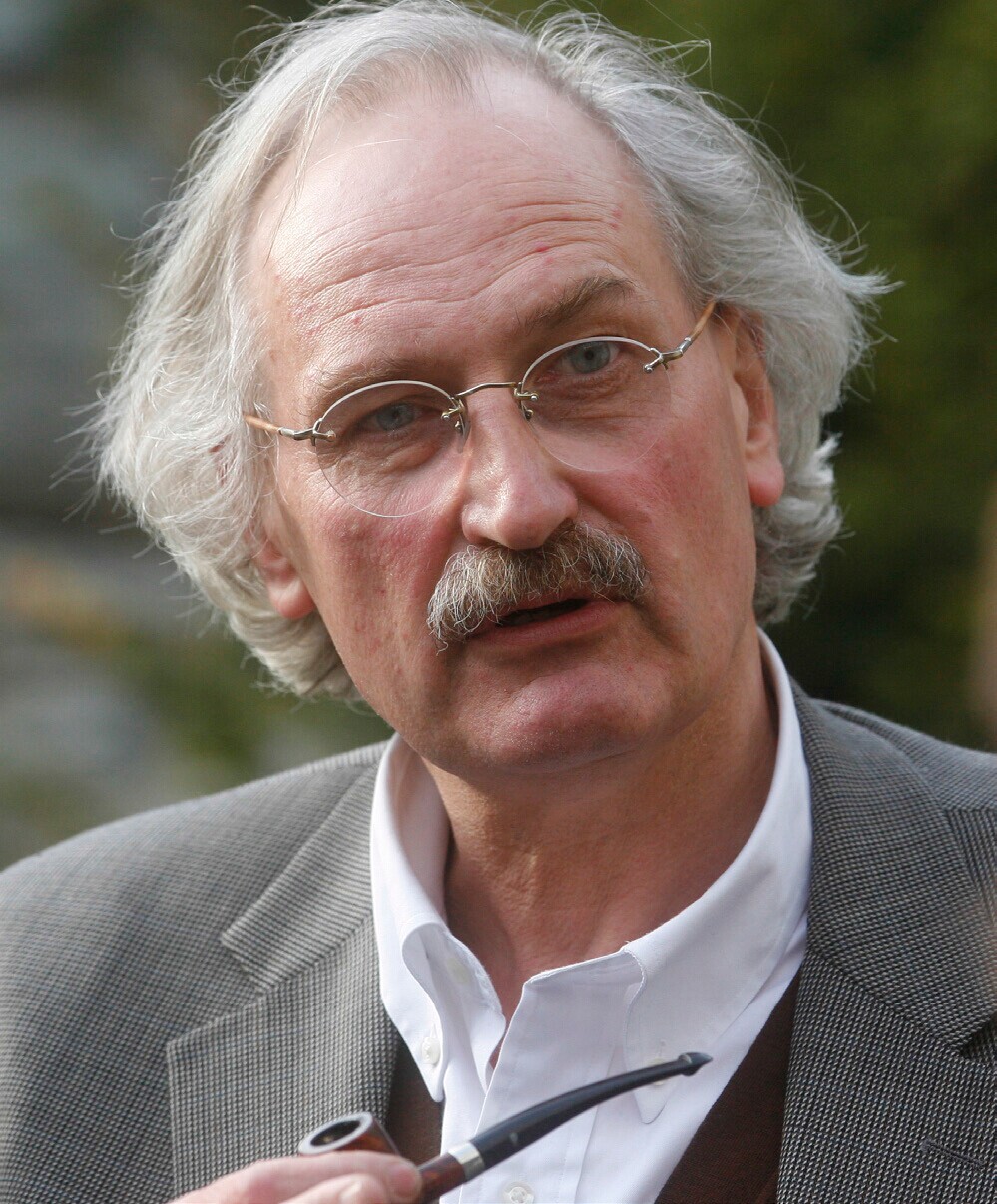

G.W.F. Hegel (left) who proposed a recognition paradigm to untie the master-slave dialectic; Axel Honneth (right) who has reconstructed Hegel’s recognition theory to include love, law and unity.

In the three decades that have passed since the nation implemented its reform and opening-up, many law researchers have been inspired by a famous remark of the British jurist Henry James Sumner Maine that “the movement of the progressive societies has hitherto been a movement from Status to Contract”. Contracts represent not only the ultimate goal of this period but also a portrayal of real life.

The original meaning of the English word “right” was “legitimacy” and “human rights” connotes the qualifications and legitimacy that make human beings human. The shift from human rights to legal rights is the process of moral norms being transformed into a legal system.

However, relying only on the paradigm of contracts would lead to a narrow understanding that confines the concept of human rights to interest allocation, thus neglecting its original multiple meanings.

From reason to ethics

Since the word “human” is the main part of “human rights”, the key issue is the understanding of humans. In the West, people usually take cognitive reason as a fundamental basis, and thinkers pursue reason to promote perceptual morality. To this end, they draw on relationship between man and God in Christianity and interpersonal relations in the contract theory to arrive at a holistic concept of reason. As was shown in the age of technology, however, this approach ran counter to the goal and people tried hard but to little avail.

Chinese culture adds to these a third type of relations: between the individual and the household. Be it the Greek myth of Oedipus killing his father, or the Christian belief that God created the universe, even the Enlightenment concept that man is born free—all indicate that people are either abandoned at birth, or are born and fed in other places rather than the home.

Because such a view prevailed among ethical theories, there was a theoretical vacuum vis-à-vis support for secular politics after the collapse of theocratic society. Consequently, contracts and democracy are no longer instruments but the aim of social ethics. However, the resulting side effects have been proven by history.

Chinese culture focuses on household. Regimes in ancient China took domestic discipline exercised by the head of feudal household as the fundamental principle. In fact, the development of human rights embodies the dialectical evolution of people-household relations. When an individual born and bred at home grew to manhood, he first left home to pursue liberty, then entered public life, demanding political rights to participate in the community and finally returned home whatever status and achievement he made in free competition.

By repetition of this process, the national community lives on and on. The mistake in the Western view of human rights is that it believes the relationship between man and God can be directly connected with the interpersonal relations regardless of the relationship between the individual and the household.

If the weakening of the concept of relations between man and God has undermined the notion of reason and morality, the contract model of interpersonal relations would fail to adequately explain the development of social rights. With regard to the expansion of human rights in society, individual-household relations can provide better explanations.

From contracts, freedom to love, unity

It’s undeniable that the paradigm of contracts has contributed a lot to the rapid rise of national economy. But the paradigm has shaped one-sided power relationships that have bad influences. Since people are regarded as carriers of interests, the more laws protect rights, the more stable the relation of the primary distribution of wealth and benefits is. Consequently, interpersonal relationships do not become free and equal as expected but instead turn into a master-slave dialectic.

As the economy continues to develop in China, improving the people’s welfare is on the agenda. Welfare refers to the survival and development of the people. Undoubtedly, it signals that China has entered the third stage in the expansion of human rights.

In the 1990s, Axel Honneth, a German professor of philosophy, wrote an inspiring title “The Struggle for Recognition” for one of his works as the movement of neoliberalism gained momentum around the world. He noted the fatal error of contract theory and proposed a new paradigm: recognition. From freedom to social rights, it can be indicated that the interpersonal differences cannot be remedied through the freedom of contract because it fails to explain why a free individual should pay for the welfare of others.

Assuming that an individual pays a 25 percent tax equal to the cost of public services and the government levies a 35 percent tax, then how will the excess 10 percent be accepted by people? In other words, why should a free individual care for and help a stranger? Obviously, the commercial means of calculating utility is unable to provide a reasonable explanation. To demonstrate the legitimacy of the right, it is necessary to contemplate the question of whether or not friendliness and unity can be included into human rights and institutionalized.

Paradigm of recognition

From the perspective of intersubjective philosophy, Honneth has reconstructed the recognition paradigm proposed by G.W.F. Hegel to break through the master-slave dialectic. Honneth put forward three perspectives to interpret recognition: love, law and unity, thus engendering three recognitions: emotional recognition, legal recognition and social recognition respectively.

Emotional recognition relates to emotions, including parental, sexual and fraternal love, which together form individual-household relatedness. As mentioned above, a person, born and bred at home, enjoys love from parents. When the individual reaches adulthood, he leaves home to struggle for recognition of independence and develops legal relationships by participating in public life.

Traditional legal relationships are manifest in social rankings. When individual legal appeals become dissociated from social status, the principle of universal equality comes into being, predicating modern legal relationships. Now, all members have gained legal recognition and are entitled to freedom and political and social rights. However, the more respect legal recognition shows for individual will, the more unable it is to recognize the individual particularities.

Therefore, we should turn to the third recognition, unity, the benchmark of which is the contribution of individual particularity and abilities to the community. Social recognition shows respect for individual morality and contribution based on reputation. For starters, economic development and scientific progress have provided a wealth basis and social innovation for emotional and legal recognition. Second, this brings a sense of pride and honor to individuals, thus solidifying the unity within the community.

Though he put forward the three recognitions, Honneth was unaware of specifying standards for each kind of recognition, which is a key problem. If the standard for legal recognition is interest, and freedom and social rights thus can be converted into each other, then the standard for social recognition is labor, which is a benchmark for the judgment and formation of love and social unity.

It can be seen that the three recognitions can associate with each other through the two standards: interest and labor. On such a basis, love, law and unity can be realized. Anyone who talks about the protection of human rights should give recognitions from the three aspects in order to unify the freedom, participation rights and livelihood contained in human rights. Since to protect human rights means to recognize the qualifications and legitimacy that make humans human, love, law and unity are necessarily included in the protection of human rights. Such protection, in the final analysis, is the institutionalized result of individual-household relations.

In the traditional period, focus was put on social status, while in the modern civil society, attention was paid to economic contracts and freedom. Then the focus has shifted again to the paradigm of recognition of love, law and unity.

No matter in the West or in China, the topic has returned to the individual-household relations. In other words, the traditional social status gave way to contracts and freedom, and after the breakout of economic crises, individual freedom and contracts were also negated. People then turn to the paradigm of recognition from the perspective of the individual-household relations. This is the so-called protection of human rights.

The historical return makes protection toward people in both ancient and modern times grow to be more coherent.

Zhang Yan is from the Law School at Renmin University of China.

The Chinese version appeared in Chinese Social Sciences Today, No. 633, August 13, 2014.

Translated by Ren Jingyun