Memories of Zheng Zhenxiang

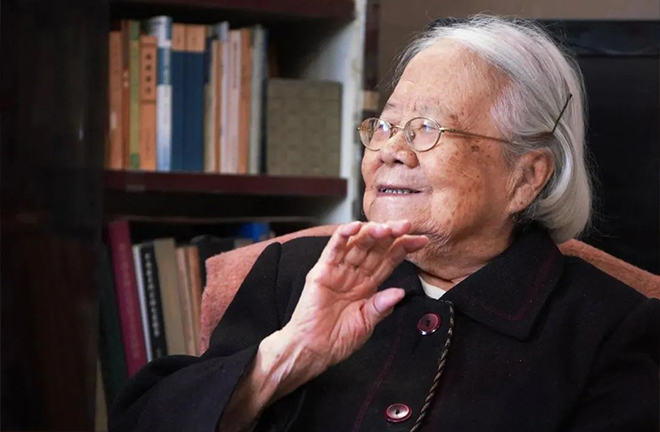

FILE PHOTO: The Chinese archaeologist Zheng Zhenxiang

The news of the passing of Zheng Zhenxiang (1929–2024) on the morning of March 15, 2024 came as a profound shock to me, leaving me deeply grieved. These days, I find myself missing her terribly. She was the mentor who guided me into the field of Shang Dynasty archaeology.

The first time I met Zheng was in 1960, when the renowned archaeologists Li Yangsong and Yan Wenming led us, the students from the 1957 Archaeology Class at Peking University, to begin an internship at the Wangwan site in Luoyang, Henan. One morning, Zheng, then the leader of the Luoyang Archaeological Workstation of the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, visited the site with Li Yangsong. Dressed simply in a blue-black outfit, she revealed her keen interest in the house foundations, ash pits, and pottery shards we unearthed.

The second time I met her was in the autumn of 1961, when ten classmates and I, including Guo Dashun and Gao Wei, conducted specialized internships at the Luoyang Workstation. I was tasked with sorting out materials from dozens of Zhou Dynasty tombs at the Wangwan site, with Zheng as my mentor. She guided me in selecting typical pottery specimens at first, then taught me how to sketch each piece, make cards, and write descriptions. The descriptions had to be simple and incisive, capturing the main features of each vessel type. She carefully reviewed each card I made, offering precise feedback on necessary revisions. After completing the cards, we proceeded to organize the pottery and drafted a preliminary report, which was subsequently submitted to Zheng for review and revision. Her patient guidance and rigorous standards enabled me to grasp the methods of organizing archaeological data, a skillset from which I have been benefitting ever since.

From 1972 to 2020, I worked in Anyang conducting field excavations and sorting out archaeological materials under Zheng’s instruction. Her boundless passion for archaeology and responsibility continued to impress me deeply.

In the early summer of 1976, Zheng led an excavation of a house foundation in the northern Palace area of Xiaotun site. After more than a month of excavating, we had found nothing aside from the foundation. As the work came to an end, we made one final attempt by drilling. When the probe reached a depth of 6 meters, the soil it brought up was still composed of rammed earth, hard and homogeneous. Some experienced workers pinched the soil and suggested there was nothing further below, seeing no reason to continue digging. But Zheng insisted on adhering to the procedures of archaeological excavation, which required digging until reaching undisturbed soil. Thanks to her insistence, a technician continued digging deeper. Soon, at a depth of 8 meters, surprising finds were unearthed: pieces of red lacquer and a small, sparkling jade pendant. Subsequently, a royal tomb was unveiled and became known to the world as the famous Fuhao Tomb of the Yin Ruins.

During Zheng’s tenure as the leader of the Anyang Work Team, she was a staunch advocate for integrity and strictly upheld anti-corruption principles. At the time, within the key protected area of the Yin Ruins, some village cadres intended to build houses for personal or family interests, which was a breach of official regulations. Some state-owned enterprises also intended to build factories without undertaking the necessary preliminary archaeological assessments. In an attempt to circumvent these requirements, they invited the archaeological team to attend banquets at ritzy restaurants. Zheng steadfastly refused all such invitations and advised colleagues to do the same. At the same time, she also talked with people in charge of the Anyang Cultural Relics and Archaeology Department, hoping that they could adhere to principles like the Archaeological Work Team. As a result of her principled leadership, the protection of the Yin Ruins was exemplary.

In addition to work, Zheng also expressed concern for the personal lives of her team members. In the spring of 1985, Zheng and I were excavating in the northwest of Xiaotun, where several Shang Dynasty house foundations had been discovered. After about a month of work, Zheng cleared two house foundations, F27 and F28. Inside F28, she unearthed orderly arranged pillar holes and pillar cornerstones. I also excavated four test pits and house foundations. However, after more than twenty days, I still wasn’t able to determine the scope of the house foundation or delineate its boundary lines. Zheng tried to calm me down, teaching me to patiently and repeatedly shovel and observe both the color and texture of the soil. She also sent an experienced senior technician to assist me. Eventually, I cleared a 96-square-meter house foundation, F29, the largest among the northwestern Xiaotun site. Zheng was very pleased with this discovery. During the excavation, I ended up with a splinter deeply embedded in my right index finger, causing considerable discomfort. I tried to pull it out with my left hand, but was unsuccessful. Upon hearing about my predicament, Zheng came to my room that evening and, under the glow of the kerosene lamp, she carefully removed the splinter with a sewing needle. After that, she gently reminded me to wear gloves while working at the site.

Zheng was deeply committed to supporting the technicians on her archaeological team. One technician, Liu, lived dozens of miles from the worksite. Zheng found a flat onsite for her, serving as both an office and a dormitory. Several years later, when it came time for Liu’s child to attend elementary school, they encountered another hurdle: the local school only accepted children from Xiaotun Village and the three surrounding villages. To solve this problem, Zheng had multiple discussions with the principal of school. Finally, they reached an agreement whereby the school would admit the child on the condition that the experts from the archaeological team would give lectures to the schoolteachers every weekend on historical, cultural, and archaeological topics.

Liu Yiman is a research fellow from the Institute of Archaeology at Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Edited by REN GUANHONG