Exploring cognitive mechanisms of adolescent depression

Teenagers struggling with mental health problems need access to consistent care. Photo: UNICEF

When discussing adolescent depression, the most tragic image that most readily comes to mind is of individuals in the prime of youth who choose to end their lives. However, in addition to those few who take drastic measures, a far greater number of adolescents grapple with the challenges of adolescent depression. Some express their suffering through self-harm; others withdraw into isolation, cutting off all social contact and abandoning activities they once enjoyed; still others appear sunny, cheerful, and smiling, all the while enduring the torment of “invisible depression.”

Diagnostic standards

Adolescent depression has only been recognized as a distinct psychological disorder by the World Health Organization within the past decade, when it was included in The lCD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. It is characterized by depressive mood disorders occurring in children and adolescents, often manifesting as persistent low moods, social withdrawal, self-harm behaviors, along with emotional instability and irritability. In severe cases, it can lead to social withdrawal, psychotic depressive episodes, bipolar disorders, and even extreme outcomes.

A recent survey report published in The Lancet indicates that the 15-24 age group is most affected by depression. The “2020 Depression Patient Group Survey Report” also reveals that respondents aged 18-25 attribute their adolescent depression to irreconcilable family conflicts, disappointment in academic competition, and anxiety and stress transmitted from adults, placing adolescents at the end of a societal anxiety and pressure chain.

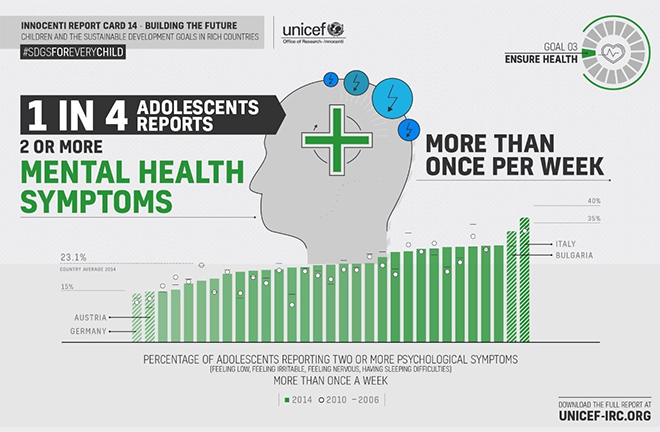

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 3.8% of the global population has experienced depression, with the incidence of adolescent depression exceeding 4%. This suggests that depression is a serious mental health issue among adolescents.

At the end of April 2023, the Ministry of Education along with 17 other departments jointly issued the “Action Plan for Comprehensive Strengthening and Improvement of Student Mental Health in the New Era (2023–2025),” which calls for standardized mental health monitoring, improved psychological early warning interventions, optimized social psychological services, and strengthened construction of child psychology consultations and specialty clinics in children’s hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, and maternal and child health institutions.

However, in current medical practice, the diagnosis of depression by psychiatrists is relatively subjective. This is due to the unclear causes and mechanisms of depression, making it difficult to perform etiological diagnoses clinically; nor can it rely on objective, quantifiable indicators like physical illnesses.

For adolescent depression, psychiatrists commonly use diagnostic standards including the “World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10/11),” the “American Psychological Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),” and the “Mental Disorder Diagnosis and Treatment Standards (2020 Edition)” issued by the National Health Commission in 2020. These standards do not differentiate between adolescent and adult depression and mostly rely on self-reporting by patients. Thus, misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis in adolescent depression are not uncommon.Exploring the psychological mechanisms of adolescent depression and identifying appropriate objective parameters for diagnosis are current challenges that clinical-cognitive psychology research needs to address.

Attention disengagement

Existing research indicates that depression is accompanied by a negative bias in information processing, meaning that when faced with emotionally charged stimuli, individuals with depression tend to notice negative emotional content more readily. Researchers generally believe that this cognitive bias in depressed individuals does not arise at the stage of attention to negative information but rather from an absence of what is termed “protective bias,” which manifests as a tendency to focus on negative information. Specifically, while typical individuals naturally react to negative information by avoiding or fleeing, the reaction of those with depression is the opposite, exhibiting difficulties in disengaging from negative stimuli. Researchers believe this difficulty in disengagement is related to emotional management disorders and sustained negative emotional experiences.

Building on the findings of previous studies, we further propose that the onset of adolescent depression is related to cognitive biases associated with developmental stages. During the growth and development phase of adolescents, psychological cognitive functions often adapt poorly due to rapid physiological changes. Some children may thus react abnormally to negative emotional information, which in this context means difficulty in disengaging attention.

To test this hypothesis, we use a classic paradigm from cognitive psychology experiments to detect cognitive differences between adolescents with depression and typical children. This paradigm, known as the “dual-target paradigm,” requires adolescents to judge the emotions of two faces within a very short interval, where assessing the emotion of the first face may interfere with their assessment of the second. By recording and calculating the nature and magnitude of this interference, we can understand the negative bias characteristics in emotional recognition tasks among adolescents. This understanding helps us identify potential factors influencing the occurrence of adolescent depression.

Experimental results conducted by team member Zhu Shasha show no difference in the ability of typical adolescents and those with depression to recognize different facial emotions; adolescents with depression also do not exhibit excessive attention or alertness to negative stimuli. However, when the emotions of both faces are negative, adolescents with depression exhibit different reaction tendencies from their non-depressed peers. We have reason to believe that this difference is due to the cognitive bias triggered by the first emotionally negative face encountered. They do not display the normal “protective bias” to quickly disengage from or avoid negative stimuli but instead allocate more cognitive resources to negative stimuli. Once these negative inputs become the primary focus of the patients’ cognitive processing, difficulties in disengagement arise.

Proposal

Through the evaluation and calculation of these differences, we further propose a hypothesis regarding the cognitive mechanisms of adolescent depression: patients with adolescent depression allocate excessive cognitive resources to negative stimuli during the information processing and neglect other inputs. This makes it difficult for patients to disengage from negative stimuli, leading to ineffective emotional management and sustained negative emotional experiences.

As mentioned earlier, research surrounding the diagnostic standards for depression mainly begins with clinical manifestations of the patient, relying on self-experience and self-reporting. For adolescents in their developmental stages, descriptions of psychosomatic experiences and somatization symptoms can be very inaccurate, leading to misdiagnoses by doctors who cannot fully understand the patient’s condition. This study employs a classic cognitive psychology paradigm to explore adolescents’ reactions to objective stimuli within a 0–235 millisecond interval. This measurement method avoids the shortcomings of subjective reporting, allowing for an understanding of the adolescents’ subconscious cognitive biases. It is therefore suitable for the fast-paced inquiry and treatment requirements of clinical outpatient settings.

From another perspective, excessive focus on adolescent depression might also lead some youth to “idolize” depression, causing them to exaggerate their emotional experiences and subjectively believe they are suffering from depression, thus providing themselves a rationale for their failures or distresses. At this time, using a method that does not involve expressing subjective symptoms to diagnose adolescent depression is a particularly suitable approach.

In the dual-target experiment, we discovered that a main component of the negative bias in adolescents with depression is the difficulty in disengaging attention. Recognizing this cognitive mechanism not only helps clinicians make cognitive diagnoses of adolescent depression but also has practical value for interventions and treatment. Clinical interventions for adolescent depression may benefit from incorporating attention disengagement training. We can expect that, with more clinical cognitive psychology research, the cognitive mechanisms behind adolescent depression will become increasingly clear; cognitive bias features could become diagnostic criteria for adolescent depression, and cognitive training could emerge as a mainstream intervention strategy.

Jiang Ke is a professor from the School of Psychiatry at Wenzhou Medical University.

Edited by WENG RONG