Mapping the evolution of delayed marriage in China

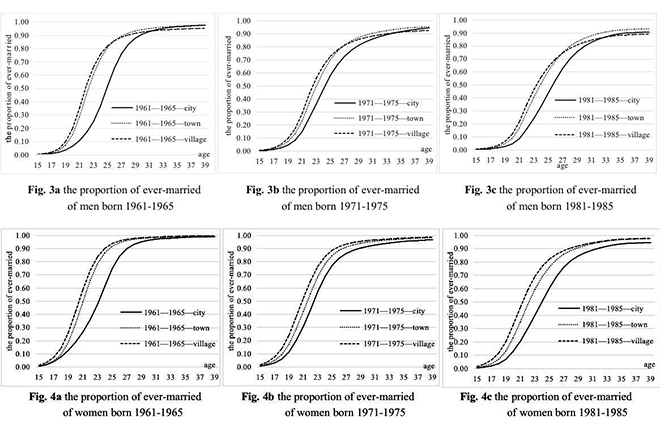

Rate of “ever-married” men and women from three different birth cohorts: 1961-1965, 1971-1975, and 1981-1985 Photo: PROVIDED TO CSST

Since the reform and opening up, people’s views toward marriage and family have evolved alongside a changing society, and as a result, people are choosing to marry at an older age. At present, there are two major problems with the existing research on this subject. First, the data lacks an urban-rural perspective which makes it difficult to reflect commonalities or differences in different regions. Especially, previous studies on marriage never explored the marital status of people in China’s “towns,” regions which have high populations and a lifestyle halfway between urban and rural, as an independent geographic unit. Second, the research does not compare marriage ages among both genders, as it often focuses on only one gender. Based on the data from the fourth to the seventh population censuses, this study systematically analyzes and explores the changing marriage landscape and the trend of delaying marriage among “urban-town-rural” populations in China over the past 30 years.

Average first marriage age

Among “urban-town-rural” populations, divided by gender, the average age of first marriage in China from 1990 to 2020 shows the following characteristics.

Overall, from 1990 to 2020, we see the same trend — ages increase and marriage delays. This is a common feature of modernization and is frequently discussed in post-modernization theory. The average age at first marriage among urban men and women is consistently higher than that for men and women in towns and rural areas, suggesting that marriage delays are more frequent in urban settings.

The “urban-town-rural” regional gap in the average age of first marriage widened further from 1990 to 2010, and narrowed significantly from 2010 to 2020. Thus, from 1990 to 2010, there was a large differentiation in the postponement of marriage from cities to towns and villages in China; however, this trend reversed from 2010 to 2020. This may be explained by the theory of cultural diffusion. Cultural diffusion leads to cultural convergence, which can be seen in the consistent delay of marriage regardless of regional population density and the narrowing gap of first marriage age differences across China.

From 1990 to 2010, the average first marriage age increased the most among urban men and women, followed by those in towns, and then in rural areas. This phenomenon reverses in 2010-2020, when the average age of first marriage for men and women in rural areas rises faster than in towns and cities. In contrast, in that period of time the average age of first marriage for men and women in cities had become relatively stable, so that the age gap between “urban-town-rural” populations narrowed significantly between 2010 and 2020.

In a comparison of delayed marriage trends among cities, towns, and rural areas, we find an interesting evolution: as a go-between region, the average age of first marriage in towns, which had been increasing in speed, has also settled in the middle, falling closer to the average age of those in rural areas.

Age-specific first marriage rate

Our study tracked age-specific first marriage rates among three different birth cohorts: from 1961 to 1965, from 1971 to 1975, and from 1981 to 1985. By charting the frequency of first marriages among each generation, new conclusions were revealed. Here, we used the age-specific first marriage rate to track the numbers of marriages registered by each age range during a fixed period of time, and performed a regional comparison against a corresponding sample from China’s total population with the same birth years.

From the start, both men and women are delaying marriage in cities, towns, and villages. This trend is reflected in our age-specific graph of first marriage frequency: the later birth cohort’s marriage curve is flatter than that of the earlier birth cohort, and the curve is shifting to the right. This means that regardless of the city, town, or village, the frequency of first marriage for men and women shows continuous decline in the younger generation, in particular for men under 25 and women under 23. The shift to the right in declining sections of each curve indicates that the frequency of first marriage has increased among older populations, indicating that marriage is still occurring, simply later in life.

Next, the frequency of first marriage among set age cohorts is highly convergent between towns and villages, whereas urban areas follow their own pattern. The age-specific first marriage frequency rate for urban men and women is significantly different from that of towns and villages, regardless of the graph’s shape, the peak frequency level for age-specific marriages, the corresponding age of the peak, or the proximity of the curve. In all the aspects listed above, the graphs for men and women in towns and villages is identical.

Why is the marriage pattern for the populations of towns similar to those in villages? Once more, cultural diffusion provides an explanation. On the one hand, the modern cultural diffusion experienced in China’s cities, towns, and villages no longer follows a traditional step-by-step diffusion process. Instead, it appears to follow a “synchronous diffusion” approach. On the other hand, as population mobility increases, we are starting to see that the modern cultural diffusion of cities, towns, and villages has formed a new feature — leapfrog diffusion.

At the same time, the age-specific first marriage frequency chart revealed that marriage norms are moving from “constrained” to “unconstrained.” Our study shows that with the older birth cohort (born from 1961-1965), the curve of the age-specific first marriage frequency chart decreases significantly after passing the peak “first marriage age.” This peak is different for men and women in cities, towns, and rural areas. After passing this peak, the declining section of the curve seems to be constrained. This suggests that for this generation (1961-1965) people’s first marriages tend to occur before a certain age, and normally within four years of the peak regional first marriage age for each gender. After that peak, there appears to be a constraint upon marriage. Perhaps this group believes that first marriages must be performed by a certain age at the latest, though this “standard age” varies by region — city, town, and village — and by gender. For those born in the later birth cohort (born in 1981-1985) the age-specific first marriage rate curve is displaying a gradual decline, revealing a diminishing role of original “constraint” factors, or “unconstraint.” The intermediate birth cohort (born 1971-1975) is in a transitional state between the two different birth cohorts mentioned above.

Finally, the age-specific first marriage frequency charts produced are moving from differentiation to convergence. The frequency distribution and age-specific trends for first marriages are similar in towns and villages, while the urban areas remain distinctive, with a flatter peak and a wider curve. In the lowest age group (15-24 years old), the age-specific first marriage frequency is the highest in rural areas, the middle in towns, and the lowest in cities. In the high age group (25 years old and above), the age-specific first marriage frequency for urban men and women is surpassing that of towns and villages, ranking first. This shows that modernity and post-modernity are what leads the trend to delay marriage for men and women in cities, towns, and villages.

If we examine the age group whose marriages have seen the largest shifts and delays, 15-25 years old for men and 15-23 years old for women, it is easy to see differences in the “urban-town-rural” age-specific first marriage frequencies. When we compare the birth cohort from 1961-1965 to the 1971-1975 birth cohort, between cities and towns, and between cities and villages, the age-specific first marriage rates are narrowing. Meanwhile, within the 1971-1975 birth cohort and the 1981-1985 birth cohort, between cities and towns, and between cities and villages, disparities were slightly wider, but still lower than those in the 1961-1965 birth cohort.

‘Ever-married’ rate

The next part of our discussion is the proportion of “ever-married.” It represents the cumulative trend in first marriages for a given cohort of the population. According to data from the sample of Chinese men and women who had been married in three birth cohorts, from 1961 to 1965, from 1971 to 1975, and from 1981 to 1985, in cities, towns, and rural areas, the following characteristics can be observed. Here, the “ever-married” rate is defined as the number of people in a cohort who have experienced marriage divided by the total number of people of that cohort in each age group.

First, for a period of time there was an uneven gender structure among the marriageable population, known as the “marriage squeeze.” This caused the proportion of ever-married men in rural areas to be “surpassed” twice, as seen in the graph printed above. An examination of the proportion of ever-married men at a certain age in urban, town, and rural birth cohorts revealed that the proportion of ever-married men in rural birth cohorts is “surpassed” at about 26 years old and 33 years old by men in towns and in cities, respectively. We can see that marriage delay is more severe with urban men, but as men age, the possibility that a rural man will find a spouse sharply declines. The proportion of ever-married women within each birth cohort shows that women in the countryside are married in higher frequencies than women in towns, and that frequency is higher than women in cities. This indicates that the marriage probability for women in each age group decreases as we move from the countryside, into towns, and cities.

The proportion of ever-married men in rural areas has been “surpassed” twice, while the proportion of ever-married women in cities, towns, and villages has remained stable, which is closely related to the “marriage squeeze” that China is now facing — and will continue to face for a long time to come.

Second, the “urban-town-rural” age-specific ever-married rate also shows “unconstraint.” The pattern for the proportion of age-specific ever-married men and women is basically the same, regardless of geographic location, with the curve slowly climbing at first, then experiencing a rapid rise, then falling back to a stable rate approaching 1.

Third, the “urban-town-rural” age-specific ever-married rate also trends from differentiation to convergence. Our study shows that the “urban-town-rural” age-specific ever-married rate in the earlier birth cohort (born 1961-1965) diverges during the rapid rise stage. In the middle cohort (born 1971-1975), the relative position of the curve is significantly closer among regions. Even though the relative position of the late birth cohort (born 1981-1985) is somewhat different from that of the middle birth cohort, the change is marginal when compared to that of the earlier birth cohort (born 1961-1965).

Fourth, the ultimate result of the delay in marriage is the rise, and differentiation, of the proportion of people who remain unmarried throughout their lives. The difference between the end points of the earlier birth cohort (born 1961-1965) was small, with the final result reaching convergence (close to 1). However, in the later birth cohort (those born between 1971 and 1975 and those born between 1981 and 1985), the relative position of the end points on the right side of the curve continues to expand, meaning the original convergence trend has ceased, and the gap between the end points of the ever-married rate curve has moved from small to large and is further widening. The end point on the right of the curve indicates the cumulative ever-married population in this cohort, and it can also reflect the proportion of people in this cohort who never marry. As can be seen from the above analysis, the final result of marriage delay may lead a significant number of people to never get married.

In conclusion, structural constraints and cultural changes have led to a “first differentiated and then convergent” evolution in first marriage trends for men and women in China’s cities, towns, and villages. Changing patterns in the first marriage age among the populations of towns and rural areas is strikingly similar, showcasing the impact of cultural diffusion.

Shi Renbing and Ke Shuqi are from the School of Sociology at Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Edited by YANG XUE