Knowledge system key to building an educational powerhouse

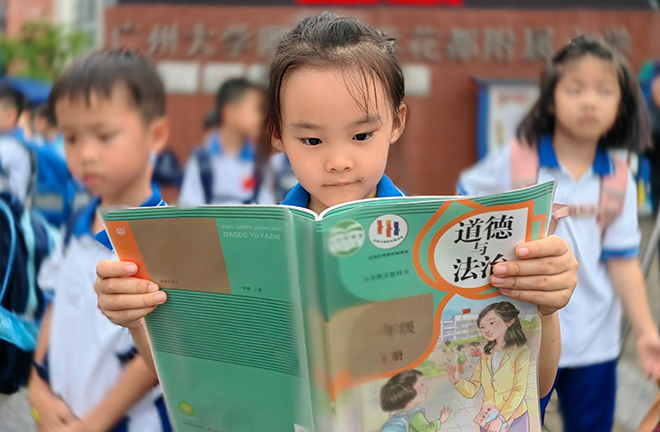

A primary school student reads Morality and Rule of Law in front of her school in Guangzhuo, Guangdong. Photo: Weng Rong/CSST

General Secretary Xi Jinping said that strengthening education is fundamental to China’s pursuit of national rejuvenation. A comprehensive knowledge system that explains and articulates a country’s own ideas is a fundamental aspect of any civilization. To advance the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, it is key to reconstruct China’s unique knowledge system.

In modern times, the rise of education powerhouses has typically coincided with the maturation of their own education thinkers and theoretical frameworks. From Locke’s gentleman’s “moderate knowledge” to Rousseau’s naturalistic education, Kant’s theory on education and Johann Friedrich Herbart’s Herbartianism, and John Dewey’s theory of democracy in education, the emergence of world-class education nations is not solely defined by advanced education systems and elevated national qualities, but also by the underlying educational ideologies and theoretical frameworks that shape their educational systems and practices. Since Chinese scholars began translating Western pedagogical theories in 1901, Chinese education has evolved from “education in China” to “the sinicization of education” and finally to “Chinese education.” Over the past century, Chinese education has transitioned from being an apprentice to Western education to becoming independent.

Educational knowledge system

China’s pedagogical system must embody its national features. General Secretary Xi Jiping emphasized, “Without the 5,000 years of Chinese civilization, there would be no Chinese characteristics; without Chinese characteristics, there would be no success in the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics.” While foreign education systems can be emulated, educational practices can be referenced, and educational ideologies can be borrowed, the path to becoming an educational powerhouse must be intrinsically derived and independent. The rationalism of Germany gave birth to Humboldt’s modern university concept, while the pragmatic philosophy of the US gave rise to Dewey’s democratic education. Influential educational thoughts and theories are inevitably rooted in cultural traditions, which serve as the historical genes and cultural core of an educational powerhouse. China has a history of thousands of years. The ideas of the pre-Qin “Hundred Schools of Thought” were as numerous as the stars in the sky, leaving behind enduring classics like The Analects, Xue Ji, and Exhortation to Learn. The Confucian ideas of “teaching without discrimination,” “adapting teaching to individual abilities,” “progressive learning,” and “integrating knowledge with practice,” as well as the Daoist idea that “in the pursuit of learning, knowledge is increased daily; in the pursuit of Dao, actions are reduced daily,” have always been the “roots” of innovation in Chinese pedagogy .

China’s pedagogical system must also embody originality and contemporaneity. China’s educational originality and individuality is evident in the formation of Chinese educational schools and the proposition of distinctive educational concepts and theories. In modern times, as education was introduced as a “foreign commodity,” Chinese intellectuals, who had experienced both Chinese and Western educational practices, strived to construct indigenous Chinese pedagogy. Cai Yuanpei, with his ideas of “replace religion with aesthetic education,” “academic freedom” and “inclusiveness and tolerance,” Huang Yanpei’s thoughts on vocational education, Tao Xingzhi’s “life education,” Chen Heqin’s “living education,” and Liang Shuming’s rural education, all serve as exemplary explorations of localized educational thought. Since the 80s, major discussions on the essence of education sparked a new wave of liberation in educational thinking, leading to the “collective glory of an era.”

China’s pedagogical system must also be systematic and professional, as the discipline of education is not regarded as highly as others in the academic hierarchy of philosophy and social sciences. In 1806, Humboldt established modern pedagogy on the basis of ethics and psychology, making education a field applied to other areas of philosophy and social sciences. After World War II, the rise of social sciences led to the infiltration of disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, sociology, economics, political science, cultural studies, anthropology, and statistics into the realm of pedagogy. This transformation resulted in the diversification of education, giving rise to multiple pedagogies and raising concerns about the potential demise of a unified pedagogical approach. Concurrently, within the field of pedagogy, sub-disciplines such as curriculum and instruction, moral education, school management, educational technology, higher education studies, and early childhood education emerged.

In the pursuit of scientific rigor, pedagogy has gone through two tendencies: “internalization” and “externalization,” leading to the fragmentation of pedagogical knowledge. The lack of internal logic within the field has directly affected its explanatory and critical capabilities, which has often led to the external criticism of it being a “useless discipline.” What China’s pedagogy needs is a balanced approach that combines openness to scientific inquiry with a focus on core disciplinary knowledge. This approach should emphasize enhancing the explanatory and critical capabilities of pedagogy.

Independent educational system

In order to foster self-reliance in Chinese pedagogical knowledge, it is essential to establish independence in Sino-Western relations. Immanuel Wallerstein, an American scholar, has highlighted that social sciences such as history, political science, economics, sociology, and anthropology, which emerged in the 18th century, have primarily focused on the experiences and issues related to the transformation of Western capitalist nations. Western social sciences are built upon pre-existing assumptions such as “rational individuals,” “political beings,” and “modernity,” making them situationally applicable but not necessarily suitable for China’s traditional culture and cognitive paradigms.

Facing uncertainties brought about modern technology, UNESCO emphasized the importance of humanistic and ethical values in the development of human society in various influential reports, including “Rethinking Education.” Chinese traditional cultural values, such as “benevolence, people’s welfare, honesty, justice, harmony, and seeking common ground while reserving differences” can offer valuable insights for the holistic development of humanity, fostering liberation, and the establishment of a global community with a shared future for mankind. In 2018, the OECD initiated a Study on Social and Emotional Skills, which aligns with the values emphasized in traditional Chinese culture, such as “learning to become a better person, placing virtue first, showing compassion to others, and self-improvement to benefit others.”

Another aspect is the attainment of autonomy in both internal and external relationships. Education is more accessible compared to other social sciences such as economics or sociology. Individuals with some experience in education or those who have contemplated educational matters can contribute to developing educational knowledge. Certain university administrators, even without specific training in educational disciplines, can serve as doctoral advisors in education based on their professional experience. In the academic arena of education, political logic, economic logic, and social dynamics frequently transcend academic logic and become dominant rules.

In activities related to discipline development, degree granting, paper publication, project evaluation, academic assessment, and academic conferences, there is a growing call for academics to adhere to the rules of academia and resist the erosion of non-academic logic such as “official power equals academic influence” and “academic capitalism.” To enhance the academic self-discipline, we must adhere to the rules of the academic field and resist the influence of non-academic logic, while stimulating internal academic vitality. This prevents academic stagnation and hinders knowledge innovation due to the “solidification” of academic hierarchies and rank structures.

Another aspect to consider is the need for self-strengthening within disciplinary relationships. In the production of disciplinary knowledge, it is essential to first clarify the distinction between educational and non-educational knowledge. The legitimacy of each discipline is based on having a specialized research domain and specific questions to explore. However, the boundaries of the educational discipline can sometimes be ambiguous, leading to situations where it “plants in others’ fields and leaves its own fallow.” That is, it may neglect to study what it should (aspects of education beyond the school context) and investigate what it shouldn’t (economic, political, social, and cultural phenomena within education).

To establish its scientific credibility, pedagogy often incorporates theories from other disciplines, adopting a “the more, the better” approach as long as they are tangentially related to education. This can lead to a loss of direction in pursuing scientific and disciplinary goals. To establish autonomy in educational knowledge, we must engage in practical reflection based on disciplinary awareness, a disciplinary standpoint, and a disciplinary perspective. This does not mean isolating oneself from other disciplines, but rather focusing on developing a solid foundation of core disciplinary knowledge and ensuring the logical coherence of knowledge within the discipline. This also allows pedagogy to make contributions to human knowledge.

Pedagogy in an open era

First, we need to manage the relationship between Chinese characteristics and universal knowledge. According to Professor Zhang Jing from Peking University, social sciences are striving to make the world “understand China.” However, the prevalent approach often involves demonstrating our uniqueness—local features, differential models, and distinctive paths. While this approach is not entirely wrong, its effectiveness is limited. Western culture excels in conceptual thinking and theory construction, while Chinese culture excels in experiential thinking and analogical reasoning. The strength of Western academic theories largely derives from their academic expression, which possesses normativity of thought and transcends time and space. The impact of theories like human capital theory, education production functions, cultural capital, educational stratification, and mobility extends far beyond Western capitalist countries. Neglecting rational thinking, conceptual expression, and theory construction will result in empirical knowledge that is localized and specific to certain phenomena, with no relevance to other regions or cultures. When constructing China’s educational system, we must be cautious of populist tendencies that overly emphasize uniqueness. We must refine local experiences and enhance academic expression of public knowledge. By moving from the specific to the general, China can contribute its theories to the world’s educational knowledge base while avoiding an excessive focus on particularity and popularity.

Second, we must enhance the subjectivity and originality of Chinese educational studies. Since the reform and opening-up, original knowledge in Chinese education has been generated by a group of scholars with deep knowledge and shared collective experiences. These scholars have integrated Marxist ideology with specific educational practices and China’s outstanding traditional culture. Based on Marx’s understanding of the essence of humanity, Ye Lan pointed out that Chinese pedagogical theory needs to transition from the “abstract individual” to the “specific individual.” Grounded in Marxist dialectical materialism and the theory of practice, Lu Jie proposed “adaptation and transcendence of education” to clarify theoretical dualisms such as the “omnipotence of education” and the “incompetence of education.” Starting from the cultural foundation of education, Gu Mingyuan pioneered research on the relationship between the traditional culture of the nation and the modernization of education. Pei Dina promoted subject-based educational experiments. Third, we should build systematic discourse strategies for Chinese education. In explaining Chinese educational practices, it is essential to seize the initiative in discourse. Knowledge production follows “first come, first serve” principle, and if we do not emphasize the academic “occupation” of China’s rich practices, these areas could become territories dominated by others, leaving our academic research in a passive follow-up state. We must enhance the academic expression, develop new concepts, categories, and expressions, and gain “Chinese experience with international expression.”

Meng Zhaohai is the deputy director of the National Office for Education Sciences Planning at China’s National Institute of Education Sciences.

Edited by WENG RONG