Synergetic governance protecting workers’ rights in digital economy

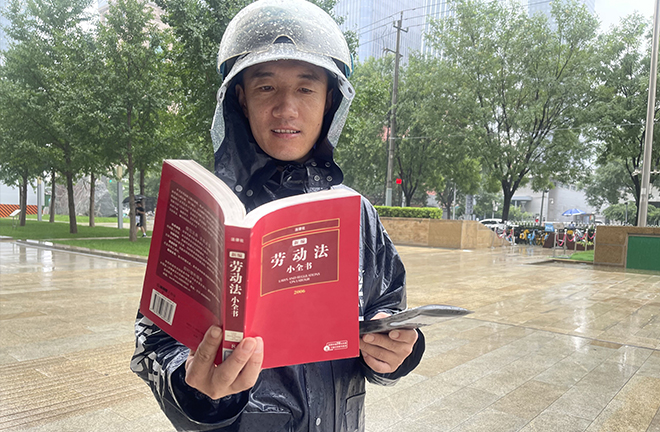

A food delivery man reads a book about labor law to gain knowledge about his legal rights. Photo: Weng Rong/CSST

The issue of safeguarding the rights of workers in new employment forms has gained attention, as highlighted by the latest findings of the “Ninth National Survey on the Status of the Workforce.” The survey reveals that the total number of employees in China has reached 402 million, in which 84 million are engaged in new employment forms. This growing population of workers in non-traditional employment has prompted a focus on ensuring their rights and protections. The significance of this matter is evident, not only in terms of population perspective and the proportion of workers involved but also in the observed growth rate.

Building on years of discussion, the Ministry of Human Resources and seven other departments jointly issued the “Guiding Opinions on Maintaining the Labor Rights and Interests of Workers in New Employment Forms (hereinafter referred to as the Opinions).” Outside of labor and civil relationships, it introduced employment forms that do not fully conform to established labor relationships, while adopting the approach of endowing non-labor relationship employment with workers’ rights, to address the problem of ‘no labor relationship means no rights.’ Additionally, concerning the phenomenon of platform employment characterized by the disintegration and de-organization of labor processes, the Opinions introduced the concept of shared responsibility, which entails the involvement of platform enterprises, outsourcing companies, dispatching units, and other relevant parties in cases where third-party involvement is involved to resolve the issue of responsibility sharing.

However, the adjustment of employment relationships amid the new employment environment is not solely a matter of ensuring labor security. Instead, it is a market-driven phenomenon that requires a broader perspective. The Opinions calls for “integrating the safeguarding of workers’ rights into the synergetic governance of the digital economy,” a perspective that is often overlooked.

Synergetic governance

The market economy necessitates the legal adjustment of labor resource allocation, a fundamental aspect of this economic system. When viewed from a historical standpoint, the unique nature of labor requires additional measures beyond the general laws of the market economy, such as civil law and competition law. As a result, labor laws play a crucial role in providing specialized protection for workers. Labor law is not intended to replace other laws of the market economy but rather to correct and complement them. Following this logic, concerns pertaining to workers have always extended beyond the realm of labor law. Labor law regulations never function in isolation, but rather within the broader context of the market economy. Hence, in the realm of traditional labor law, it is key to approach legal adjustments in the labor market from various angles, such as labor relations, employment relations, and similar labor-related perspectives. It is also crucial to acknowledge the influence of civil law, competition law, and other relevant factors when addressing employment relationships.

In the digital age, the diverse and flexible nature of employment relationships, along with the trends towards decentralization and depersonalization, have highlighted the importance of market-driven allocation of labor resources. Consequently, there is a growing need to revisit the general legal framework of a market economy, particularly from the perspective of collaborative governance in the digital economy, in order to address the issue of protecting the rights and interests of workers in emerging forms of employment. Thus, labor laws and their frameworks are a last resort safeguard, representing a reactive approach to problem-solving. On the other hand, other laws of the market economy are positioned to optimize industry and market order, representing a proactive approach to problem solving. By combining source governance with a safety net approach, we can better achieve a balance between orderly industrial development and the protection of workers’ rights in new forms of employment.

Market economy rules

The fundamental principles that underpin a market economy revolve around transactions and competition, which aim to ensure the fair allocation of rights and obligations among parties through openness, transparency, freedom of choice, and competition. Notably, regulations pertaining to information also form an integral part of the general rules governing a market economy. Firstly, leveraging market competition mechanisms will ensure the ability of workers to “vote with their feet,” by reducing various restrictions that impede workers from switching platforms, and prohibiting agreements that stop workers from being employed by multiple platforms simultaneously.

Furthermore, in order to provide workers with a wider range of platform options, we need to implement anti-monopoly and anti-unfair competition regulations. In practice, certain policies governing platform employment have already begun to focus on this perspective. The “Opinions on Strengthening the Protection of the Rights and Interests of Practitioners in New Forms of Transport Business” highlights the need to enhance monitoring of new forms of transportation operations, promptly issue warnings regarding monopoly risks, and intensify supervision and law enforcement against anti-monopoly and anti-unfair competition practices. Another document aimed at safeguarding the legal rights and interests of express delivery personnel emphasizes the importance of investigating illegal price competition. We must note that platform employment has advantages in optimizing labor resources allocation across society through vast amounts of data. However, this aspect is more easily achieved by leading enterprises, and thus excessive opposition to business concentration should be avoided.

Second, personal information protection rules are key. These rules not only concern safeguarding the personal rights and interests of workers but also serve as a market competition rule. The key characteristic of employment in emerging forms is its administration through online platforms, with information serving as a critical foundation. These platforms leverage the analysis of extensive data from both workers and consumers to optimize the allocation of labor resources. To prevent the exploitation of workers, it is crucial to tackle this issue at its core. One approach is to impose moderate restrictions on platforms regarding the collection and processing of workers’ work-related information. It is also essential to enhance workers’ rights in the realm of information, granting them more opportunities to address consumer criticisms and rectify inaccurate information. This ensures that undue pressure from consumers or other parties is not disproportionately transferred to the workers.

Open and transparent market transaction rules are key. Market choices are based on the premise of open and transparent information, as only such information can guarantee genuine autonomy for the parties involved. Regarding employment in new forms, the use of subcontracting and franchising methods introduced a level of ambiguity regarding the actual identity of the employer. Unclear and fluctuating commission rules also make workers’ core rights obscure. This situation has led to workers being unable to identify their counterparts or determine their rights. The “click-through” style of contract signing also hampers workers’ ability to access information.

To address this issue, it is key to enforce clear contract agreements between the parties and implement institutional designs that ensure transparency in platform transaction rules. The requirements stated in the current documents related to safeguarding workers’ rights in the governance of platform employment, such as signing labor contracts or written agreements, reflect the essence of this approach. The issuance of the “Guiding Opinions on Maintaining the Labor Rights and Interests of Workers in New Employment Forms” by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS) in 2023 also aligns with this governance perspective.

Last, we need to introduce regulations for standardized contracts, particularly those commonly used in the digital era, such as those entered into between workers and platforms, often referred to as “click-through” contracts. Before applying the rules of labor law, when examining a platform’s labor contract, it is worthwhile to explore the possibility of applying the explanations or rules in the Civil Code, including Articles 496, 497, and 498. These articles emphasize the importance of fairness in defining rights obligations, reminding parties of provisions that greatly affect the other party, and addressing obligations related to invalidity or lack of understanding,

When conducting a rationality review of the terms in standard contracts, any discrepancies identified between the contract terms and the labor contracts, and written agreements recommended by the MOHRSS in new employment forms, can serve as preliminary evidence of potential unreasonableness. But this presumption can be rebutted if the platform or the employer can prove there are other reasonable justifications.

Two protection strategies

In safeguarding workers’ rights, traditional labor laws follow two distinct paths: production process control and safeguarding workers’ rights at the bottom line. The former involves using legal regulations or worker participation to limit employers’ organizational control over the production process. The latter entails the intervention of public authority or the establishment of collective agreements to directly determine labor rights for workers, such as regulations on maximum working hours, rest periods, minimum wages, and other labor-related conditions. The underlying logic of these two paths remains applicable in the context of platform employment, where regulating algorithms focus on controlling the production process, while principles like equal employment, minimum wages, labor conditions, and collective bargaining aim to provide basic protection for workers’ rights.

Specifically, caution should be exercised in algorithm control. In the practice of organized production, modern labor laws allocate production organization authority and business risks to employers. The employer’s right to organize and direct work and the corresponding obligation of workers to obey instructions and follow rules, are critical criteria for determining the employment relationship. Despite various countries implementing worker participation mechanisms to protect workers’ rights and limit employers’ organizational control, the fundamental principle that employers have authority over production organization is not altered.

In the digital age, the consensus is to regulate algorithms and prohibit the use of overly strict algorithms, as it is recognized that platform workers can find themselves “trapped within the system.” However, this pattern is fundamentally shaped by the characteristics of production process control within labor regulations. Algorithms serve as a manifestation of managerial authority and carry complex production and business confidentiality requirements. Controlling algorithms is primarily concerned with procedural and rational control, rather than substantive control over their content. Given the limited scope for procedural control and the allocation of production organization authority to employers, safeguarding workers’ rights becomes a focal point of modern labor law regulation. Regardless of the method of production organization, safeguarding workers’ fundamental rights and enabling collective bargaining to optimize workers’ rights remain essential.

Due to the increased difficulty of algorithm control over production organization, the importance of protecting workers’ fundamental rights and optimizing these rights through collective bargaining will continue to increase. It must also be noted that, to safeguard workers’ fundamental rights and their ability to engage in collective bargaining within the context of platform employment, existing labor law systems directly is not enough. Instead, it requires the development of unique labor standards and collective bargaining rules that are tailored to accommodate the flexible online and offline schedules of platform workers, and their potential to work across multiple platforms.

Shen Jianfeng is the dean of the School of Law at the China Institute of Industrial Relations.

Edited by WENG RONG