Ye Shengtao made Chinese fairy tales from a wilderness

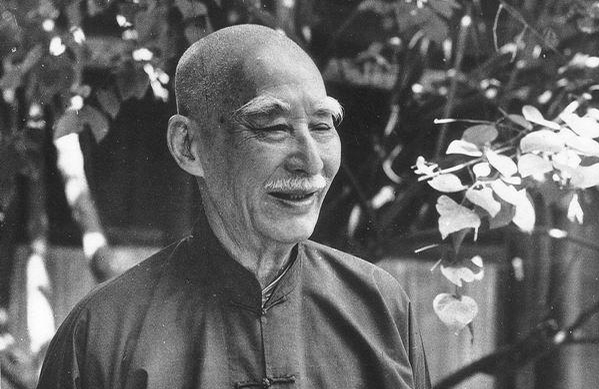

FILE PHOTO: The inspiring Chinese writer and educator Ye Shengtao

In 1903, the Chinese translator Zhou Guisheng’s two-volume Xin’an Xieyi was published. The first volume is the translation of selected stories from Arabian Nights, and the second includes the translations of Aesop’s Fables, Grimms’ Fairy Tales, and Hauff’s Fairy Tales. From then on, the term tong-hua (fairy tale) began to spread in China. In 1908, Sun Yuxiu planned and edited the “Fairy Tale Series,” in which he referenced fairy tales such as the Fifty Famous Stories by James Baldwin, and created new works including “A Kingdom Without Cat” and “The Thumb.” The renowned writer Mao Dun praised him as the “the founder of China’s fairy tales.” In 1909, the great Chinese writer Lu Xun and his younger brother Zhou Zuoren published their translated work, the first volume of Yuwai Xiaoshuoji (Collection of Stories from Abroad), which included Oscar Wilde’s “The Happy Prince.” In September, “A Rose From Homer’s Grave” by Hans Christian Andersen was included in the second volume of this collection, marking the first time Andersen’s name was mentioned by Chinese writers. From 1912 onwards, Zhou Zuoren encouraged writers to “cultivate” children’s literature “from a wilderness.” Ye Shengtao (1894–1988) created the first collection of fairy tales in the history of Chinese children’s literature, The Scarecrow, between 1921 and 1922, paving the unique way for Chinese fairy tales.

Fairy tales in classroom

In the spring of 1912, after graduating from high school, Ye began teaching at an elementary school in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. In his “self-cultivation” class, Ye taught topics such as “diligence” and “independence,” equivalent to oral “children’s literature.” Sometimes, Ye also told stories adapted from Chinese and foreign classics, as recorded in his diary: “In the second ‘self-cultivation’ class, I talked about ‘independence.’ The story I told my students was the adventures of Robinson Crusoe. All the kids were heartily glad. Hearing things that has never been heard is usually a lot of fun, especially for children. Thus, I took the opportunity to talk about the admirable deeds of ancient people, which was beneficial” (June 10, 1912).

In Jan 1922, the weekly magazine Children’s World was first published, with Zheng Zhendo as the editor-in-chief. In support of Zheng, Ye worked tirelessly to write fairy tales even before the magazine launched. His first fairy tale, “Little White Boat,” was written on Nov 15, 1921. By June 1922, Ye had written a total of 23 fairy tales, which were compiled into The Scarecrow, and published in 1923 by the Commercial Press in Shanghai. It is the first collection of fairy tales in the history of Chinese children’s literature.

‘Beautiful fairy tales’

The fairy tales in The Scarecrow can be divided into two categories. The first one is “beautiful fairy tales,” featuring “childhood dreams” hidden between the lines, innocent smiles, and beautiful feelings, as depicted in the opening of “Little White Boat”: A small stream is home to all sorts of lovely things. Little red flowers stand there, smiling and sometimes even dancing beautifully. Dewdrops adorn green grass, shining like fairy clothes, dazzling the eye. The surface of the water is covered with green duckweed, with yellow flowers blooming like tropical water lilies—they are the water lilies from “Lilliput.” Tiny fish with big shining eyes swim in groups, as fine as embroidery needles. A frog stares with his eyes wide open—don’t know what he is doing—perhaps he is waiting for his best friend.

The story of the fairy tale unfolds in this delightful atmosphere. The main characters are a boy and a girl on a little white boat, playing, singing, and exploring a creek full of life and joy. Suddenly, a strong wind blew the boat downstream, which finally reached a great desolate wilderness, where the kids met a terrifying yet kind-hearted giant. The giant offered to send them home if they could answer his three questions: “Why do birds sing?” “Why are flowers fragrant?” “Why did you sail in the little white boat?” The children’s answers were: “Birds sing for the ones they love;” “Fragrance comes from goodness, and flowers symbolize goodness;” “Only we can sail in the little white boat because we are pure.” The answer to the last question is meaningful. The little white boat represents purity and innocence in children’s world. In this fairy tale, all the vitality of nature is rooted in love. It considers “love” and “beauty” as the law of survival, which connects the innocent children with the giant’s heart.

‘Sorrow of adults’

The second type of fairy tales in The Scarecrow refers to those fused with “the sorrow of adults.” Although Ye’s “beautiful fairy tales” catered to children’s curious nature and received high praise from the literary world, he was not satisfied. A new style came into being when he wrote “A Happy Man.”

“A Happy Man” depicts a man who always saw everything as joyful and everyone as happy despite the presence of unreasonable situations and individuals with a full share of misfortune. The reason was that “the happy man” lived under a mysterious and transparent cover which prevented him from seeing the truth of the outside world. Unfortunately, this soap-bubble-like “cover” was pierced by a “demon,” and the “happy man” died. Following the idea of “piercing the mysterious and transparent cover,” Ye created the fairy tale, “The Scarecrow.” The first paragraph of this story is as follows:

During the day, poets wrote the fields into beautiful poems, and artists painted it into vivid pictures. As the dusk shaded into night, the poets got drunk, while the artists held delicate musical instruments and sang softly. No one had the time to go to the fields. Was there anyone who can tell people about the night in the fields? Yes, the scarecrow.

In this story, Ye expressed his criticism for some writers from that era who were disconnected from rural life or lacked attentiveness in their observations. He put this phenomenon across from the perspective of a scarecrow in his fairy tale. “The Scarecrow” is filled with descriptions that are rich in childlike innocence, inviting children into a mysterious “fairytale world.” However, when young readers step into it with great interest, what they see is a “real world.” The fairy tale depicts a scarecrow, on a poetic starry night, witnessing several tragedies, one after another: worms frantically chewed on the rice leaves [on which the old peasant woman, also the creator of the scarecrow, had spent months of toil]; a fisherwoman fished on the riverbank while her son coughed constantly in the cabin, begging for tea, and the mother couldn’t do anything but to scoop a bowl of water from the river for her son; a crucian carp caught by the fisherwoman struggled in a wooden bucket, begging the scarecrow to let it go; a woman drowned herself in the river because she didn’t want to be sold to others like “a cow or a pig” by her husband, with “no other way out except death.” This fairy tale gives a glimpse of the night, exposing various tragedies in rural Jiangnan [in the south of the Yangtze River] at that time. It reveals the sadness and distress of the intellectuals with a conscience in old China.

According to Lu Xun, “The Scarecrow” opened up a unique path for Chinese fairy tales; after that, unfortunately, there was no further change in the development of Chinese fairy tales, and no one followed up. In fact, however, Ye created many more fairy tales after the publication of The Scarecrow. In 1931, he published the second fairy tale collection A Stone Figure of An Ancient Hero. Many other fairy tales he wrote were scattered in newspapers and magazines. These fairy tales offer a broader reflection of social reality, including exposure and satire of the rulers of that era. They possess a critical power of realism and some fable-like characteristics. Nevertheless, Lu Xun believed that the creation of fairy tales should meet a higher standard.

In his Essays of Qiejieting, Lu Xun emphasized that works for children should be “fresh in content” and “highly interesting,” promoting children to “continuously flourish and grow” towards “a constantly changing new world.” With such a high standard, Lu Xun felt that Ye’s fairy tales lacked sufficient progressiveness. There were several writers who “followed” Ye to write fairy tales. In 1932, Zhang Tianyi’s fairy tale Da Lin and Xiao Lin was highly praised by the literary and art circles. However, Lu Xun considered Zhang’s achievements in fairy tale creation were insufficient. Lu’s emphasis and high standards for fairy tale creation can also be interpreted as a form of acknowledgement for Ye’s achievements in this field.

Shang Jinlin is a professor from the Department of Chinese Language and Literature at Peking University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG