Tang poetry fueled mutual learning between cultures

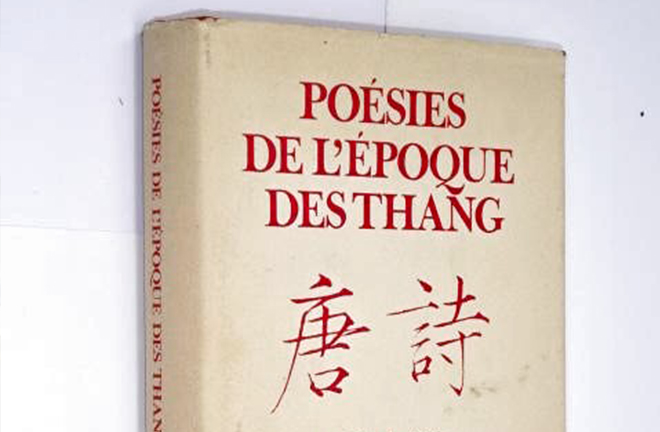

FILE PHOTO: French sinologist Hervey de Saint-Denys’s Poésies de l’époque des Thang (Poems of the Tang Era), the first translation of Tang poetry in the West

Poetry of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) has been extensively translated and studied in the West, epitomizing the overseas communication of Chinese literature and exemplifying the wide acceptance of Chinese culture in Western countries. As Tang poetry extended its reach westward, the Western world attempted to understand the spirit of the Chinese nation through classical Chinese literature, and realized that classical Chinese poetry is most typical of Chinese literature, while Tang poetry represents the height of classical Chinese poetry.

Tang Dynasty poetry entered the Western cultural view in 1735. Over nearly 300 years of transmission to the West, Tang poetry has forged a significant bond that promotes mutual learning and integration between different cultures.

Centuries of westward transmission

As early as the 18th century, French missionaries had already taken a keen interest in poetry of the Tang Dynasty. In 1735, French sinologist and Jesuit priest Jean-Baptiste du Halde made mention of iconic Tang poets, Li Bai (Li Po) and Du Fu (Tu Fu), in his compilation Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique et physique de l’Empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie Chinoise (The General History of China: Containing A Geographical, Historical, Chronological, Political, and Physical Description of the Empire of China, Chinese-Tartary, Corea and Thibet). In the eyes of sinologists, these two poets were comparable to ancient Greek poet, Anacreon, and ancient Roman poet, Horace.

In the 19th century, Tang poetry began to gain popularity in the West. Instead of being introduced frivolously as a parlor trend, the poems were deeply analyzed and interpreted. In addition to missionaries, Western sinologists and poets actively translated Tang poetry, producing a few influential translations in French, English, and German.

In 1862, French sinologist Hervey de Saint-Denys published the first translation of Tang poetry in the West, Poésies de l’époque des Thang (Poems of the Tang Era), which is still regarded as the best French translation of Chinese poetry.

The first half of the 20th century saw vigorous dissemination of Tang poetry in the West. As sinology thrived, translations diversified. In addition to France, Britain, and Germany, other countries, such as the Soviet Union, Spain, and Italy, joined the undertaking of translating Tang poetry.

Vasily Mikhailovich Alexeyev from the Soviet Union was the epitome of systematically translating Tang poems into Russian, including works of Li Bai, Du Fu, Wang Wei, Bai Juyi and other poets. His student, Julian Konstantinovich Shchutsky, joined him in co-publishing a collection of Russian renditions of Tang poems.

In the second half of the 20th century, Tang poetry continued to flourish in the West. Translations expanded to cover almost all major Western languages. A host of influential representatives and translations emerged, evidencing the popularity of Tang poetry. Cooperation between Chinese and Western scholars was a highlight in this period. For example, in 1957, renowned Chinese scholar Guo Moruo and Nikolai Trofimovich Fedorenko from the Soviet Union co-compiled the Antologiia kitaiskoi poezii (Anthology of Chinese Poetry).

Different communication groups

Over the course of nearly 300 years, due to proactive translation projects in several Western countries, Tang poetry was widely disseminated in Western cultural fields and never lost its appeal. Passionate translations divided Western sinologists and poets into two groups of communication.

The first group consisted of sinologists, including Herbert Allen Giles from Britain and Vasily Mikhailovich Alexeyev. Well-versed in the Chinese language, they showed respect for the original text by trying to preserve the images, rhythm, and linguistic features of Tang poems, while seeking to align translation with metrical requirements of their home countries.

In the second group, there were poets and writers such as French writer Judith Gautier, American poet Ezra Pound, and Alexander Gitovich from the Soviet Union. Most of them had little knowledge of Chinese, yet they were experts in poetry. Proficient in composing poems in a style unique to their home countries, they tried to strike a balance between Chinese and Western poetry by rewriting Tang poems, which attracted more readers and fueled Tang poetry’s popularity in the West.

In the process of transmission, diverse translation forms and strategies were invented. Giles was inclined to literally translate rhyming verses. In his opinion, poetry should be sung, so rhyming was essential. Otherwise, the unique characteristics of Tang poetry would be undermined. De Saint-Denys preferred a prose style in translation. Some sinologists argued that the heart of Tang poetry was not in its rhyme, but in the spirit of each poem. The linguistic rhyme should serve the imagery or essence of the poem, and the content of the original text should never be compromised for rhyming purposes. These scholars held that the meaning of Tang poetry should be expressed through phrases and sentences suited to readers’ aesthetic habits, rather than confined to a rigid match between translation and the original, calling for attention to retaining and conveying the emotional and imaginary elements of the Chinese text.

Gautier was a typical example of “creative rebellion” in translation. Creative rebellion, as a basic rule of literary communication and reception, reflected the clash between different cultures in literary translation. Despite misinterpretations, creatively translated texts of Tang poetry were extensively accepted in target language countries at the time.

Western researchers adopted the perspective of comparative literature to understand the style of Tang poetry, adding depth to its popular trend in the West, thus advancing communication and dialogue between Chinese and Western cultures. For example, French essayist and critic Émile Montégut made a comparison between Tang and Western poetry, and maintained that Chinese and Western cultures are the same at the core, yet expressed in different forms.

In Montégut’s view, Li Bai’s famous poem “Jing Ye Si” or “Thinking in the Silence of Night” is akin to a German romantic song, and there is reason to regard Du Fu’s “Chun Ye Xi Yu”, or “A Welcomed Rain on Spring Night” as a lyric piece of Scottish poet Robert Burns. Through comparison, Western scholars showcased identical or similar contemplations on the same life scenarios, demonstrating commonalities in human nature in China and the West.

Tang poetry fever

As a distinctive form of poetry, Tang poetry interacted well with poetic composition, sinology, and even artistic creation in the West.

In the Western poetry community, luminaries like Gautier and Pound translated Tang poetry with great enthusiasm. Subject to tremendous influence of Tang poems, they often would blend Chinese elements into their poetic creations. Gautier’s Le Livre de jade (The Book of Jade), a volume of French renditions of Chinese poetry, contained many pieces from Li Bai, and was further translated into German, Italian, and Spanish successively, sparking a “Li Bai craze” in the West. Her own poems were not immune from Tang poetry. For example, the sonnet “La Marguerite” (“Margaret”) employed several metaphors concerning Chinese customs.

To a large extent, due to Gautier’s love of Tang poetry, China became an important theme in French poetry circles. At that time, European poets were questing for the spiritual homeland of humanity, and Tang poetry exactly met their affective demand.

As the founder of imagism, Pound dove into Chinese civilization and chased his ideal from it by translating classical Chinese poetry into the masterwork Cathay. Out of classical Chinese poetry, he created the artistic approach of “image superposition,” promoting mutual learning between Eastern and Western poetry, and making Tang poetry a hit in the United States.

Moreover, Western sinologists were fascinated by the expression of religion in Tang poetry. For example, French essayist and poet Daniel Giraud’s Ivre de tao: Li Po, voyageur, poète et philosophe en Chine au VIIIe siècle (Drunk Tao: Li Po, Traveler, Poet & Philosopher in Eighth Century China) examines Taoism in Li Bai’s poems, and this deep analysis swept through the European sinology community. Reviewing the language of classical Chinese poetry, Giraud discussed frequently arising images in the Chinese poet’s works, and concluded that the moon, wine, rivers, and mountains are dominant themes in Li Bai’s poems. All of these themes imply “immortality,” mirroring Li Bai’s obsession with, and proactive pursuit of, immortality in Taoism.

As Western sinologists were exposed to Chinese Chan (Zen) Buddhist poets Wang Fanzhi and Han Shan, Chan Buddhism in Tang poetry became a popular focus in the West. In his essay “Le Tch’an et la poesie chinoise” (“Chan and Chinese Poetry”), Swiss-French sinologist and Orientalist Paul Demiéville pointed out that Han Shan’s poems can count as timeless classics in Tang poetry. In Han’s verses, religious thoughts were manifested via the integration of Buddhism and Taoism. In addition, Demiéville’s studies of Han Shan’s poems, and Russian sinologist Lev Nikolaevich Menshikov’s translations of Wang Fanzhi’s works, promoted Dunhuang studies in the West.

Tang poetry was also closely connected to other artistic forms like music, resonating deeply with readers acoustically and visually. Poems of the Tang era are melodic compositions and aesthetically pleasing scrolls themselves. With regard to the picturesque atmosphere in Tang poetry, de Saint-Denys said that a beautiful five- or seven-character quatrain is like a piece of exquisite brocade woven with 20 or 28 characters.

German sinologist Hans Bethge’s collection of German renditions of Chinese poetry Die Chinesische Flöte (The Chinese Flute) included works of many Tang-Dynasty poets, such as Meng Haoran, Wang Wei, Wang Changling, Li Bai, Du Fu, Cui Zongzhi, and Bai Juyi.

Die Chinesische Flöte enjoyed great popularity in the German-speaking world, drawing the attention of famed Austrian composer Gustav Mahler. In 1908, Mahler composed a symphony titled “Das Lied von der Erde” (“The Song of the Earth”), and incorporated seven German-translated Tang poems into the lyrics, creating the first symphony set to Tang poetry in the world.

In May 1998, a German orchestra performed Mahler’s “Das Lied von der Erde” during its visit to China, causing a sensation in the source of Tang poetry. The creation and dissemination of the symphony contributed a brilliant story to the history of communication between Chinese and Western cultures.

The wide spread and acceptance of Tang poetry demonstrates the huge appeal of traditional Chinese thought and culture. Also, the westward transmission of Tang poetry enhanced dialogue, mutual learning, and integration between Chinese and Western civilizations.

Li Chunrong is an associate professor from the College of Foreign Languages and Cultures at Sichuan University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG