First two solar terms usher in first breath of spring

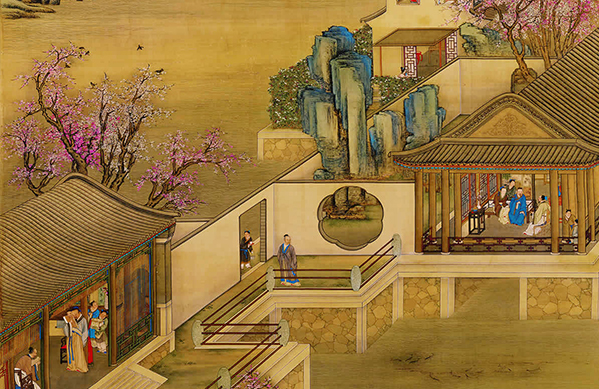

FILE PHOTO: One of the “Life Portraits of the Yongzheng Emperor throughout the Twelve Months” by anonymous Qing court artists, depicts people enjoying a spring day in the Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanming Yuan).

By Ren Guanhong

The ancient Chinese divided the sun’s annual circular motion into 24 segments. Each segment is known by a specific “Solar Term.” The earliest elements of 24 solar terms date back to the Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BCE). By the Han (202 BCE–220 CE) Dynasty, the 24 solar terms had been fully established. In the Taichu Calendar established in 104 BCE, all 24 solar terms were officially included in the Chinese calendar.

Ancient wisdom of dividing time

The criteria for the formulation of the 24 solar terms were developed through the observation of changes of seasons, astronomy, and other natural phenomena in the Yellow River basin, and were progressively applied nationwide. The solar terms have been passed down through generations and used traditionally as a timeframe to direct production and daily routines.

Starting with Lichun [Beginning of Spring] and ending with Dahan [Major Cold], each season is divided into 6 solar terms, each with a time span of 15 days. Among the 24 solar terms, the Beginning of Spring, Beginning of Summer, Beginning of Autumn, and Beginning of Winter divide a year into four seasons. The first day of Spring Equinox and Autumn Equinox are when the days and nights are of equal duration, while the Summer Solstice sees the longest day and the shortest night in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the contrary on the day of the Winter Solstice.

‘Make your whole year’s plan in the spring’

As one of the earliest eight solar terms, Beginning of Spring probably had been established in the Spring and Autumn Period. The Chinese have an old proverb: “Make your whole year’s plan in the spring and the whole day’s plan in the morning,” where the importance of the “Beginning of Spring” was fully demonstrated. Spring plowing is the initial step of agricultural activities.

The nature of agrarian society determined that the Beginning of Spring was significant in ancient China. The ancient Chinese celebrated it with various traditions and rituals.

The tradition of ying chun [welcoming the spring god] has a long history in China. Liji [Book of Rites, a collection of texts describing the social forms, administration, and ceremonial rites of the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE)] records that “in this month there takes place the inauguration of spring. Three days before this ceremony, the Grand recorder informs the son of Heaven, saying, ‘On such and such a day is the inauguration of the spring. The energies of the season are fully seen in wood.’ On this the son of Heaven devotes himself to self-purification, and on the day he leads in person the three ducal ministers, his nine high ministers, the feudal princes (who are at court), and his Great officers, to meet the spring in the eastern suburb; and on their return, he rewards them all in the court” (trans. James Legge). The purpose of welcoming spring is to bring back spring and Goumang, the spring god with the face of a human and the body of a bird. There are various performances involved in the ceremony of ying chun, such as taige [a folk dance performed with teenagers in costumes standing high on plank platforms and other people carrying poles below parading on the streets] and da chunniu [beating or whipping a fake spring ox].

The tradition of da chunniu became popular during the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) eras. This custom is often performed by four people carrying a clay sculpture of a spring ox while a fifth person dressed as Goumang whips it, a practice to drive out winter laziness and encourage farming activities. This ceremony became even grander in the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) eras.

According to Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking, a book compiled in the Qing era, one day before the Beginning of Spring, officials from Shuntian Prefecture [equivalent to present-day People’s Government of Beijing Municipality] went to the Spring Ground [a certain place for the welcoming ceremony of spring] outside the Dongzhi Gate to welcome spring. On the day of the Beginning of Spring, the Chunshan Baozuo [the Seat of the Spring God] and a painting of the spring ox were respectively presented by the Ministry of Rites and Shuntian Prefecture to the emperor and the queen. After the rituals were completed, officials returned to the seat of Shuntian Prefecture and performed the whipping of the spring ox, which was known as da chun [lit. beating spring].

“Beating the Spring Ox” started with beating a clay ox. After years of evolution, the clay ox was replaced by a paper ox, stuffed with grains. In the ceremony of welcoming spring, “Goumang” whipped the paper ox and broke the paper. The grain spilling from the body of the ox symbolized a bumper harvest for that year.

In the old days, Beijing, Tianjin, and other places in the north had the custom of yao chun, or “taking a bite of spring,” i.e., eating chun bing [spring pancakes] and raw radishes at the Beginning of Spring. The spring pancake is a thin crepe wrapped around various vegetables, eggs, and meat. Since radishes taste spicy, it is believed that one who can eat radishes is able to bear hardships and stand hard work. People in the south prefer chun juan, or spring rolls, rolled appetizers filled with vegetables and other ingredients.

‘Good rain, ever attuned to the seasons’

Over 1,200 years ago, the great poet Du Fu expressed his delight for a spring rain in Jinguan city [present-day Chengdu, Sichuan Province] in a poem: “Good rain, ever attuned to the seasons,/ Returns in spring to entice forth new life./ Trailing a wind, entering unseen at night,/ Softly, silently it showers everything./ Although rain-clouds blacken country roads,/ And riverboat lanterns alone flicker light,/ Come dawn, we see rain-fat red blooms/ Everywhere in flower-laden Brocade City [Jinguan City]” (trans. Stanton Hager).

In 2023, the solar term known as Yushui, or Rain Water, starts on Feb 19 and ends on Mar 6. Rain Water signals the increase in rainfall and rise in temperature. With its arrival, lively spring-like scenery starts blossoming: rivers thaw, wild geese migrate from south to north, and trees and grass turn green again.

In ancient China, the literati favored scenes of apricot blossoms bathed in spring rain in the Jiangnan area [lands immediately to the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River]. After the rain, people selling apricot blossoms on the street constitute unique scenery in Jiangnan, vividly captured in a poem by the Song poet Lu You: “In the inn I listen to the rain all night;/ Who’ll sell apricot blooms morrow in the lane?” (trans. Zhao Yanchun). The raindrops on the apricot blossoms reveal the breath of spring.

Each solar term is divided into three pentads [hou], thus there are 72 pentads in a year. Each pentad consists of five (or rarely six) days and is mostly named after phenological phenomena corresponding to the pentad. In Rain Water, the first pentad is known as “otters make offerings of fish.” It is derived from the ancients’ observation that as fish began to swim upstream, otters displayed fish caught in the water in a row on the shore, as if offering sacrifices to heaven. The second pentad is “the arrival of wild geese,” in reference to wild geese beginning their northward migration, following the onset of spring. In the last five days before the end of Rain Water, trees and grass put forth shoots, comprising the third pentad of Rain Water.

In the current time of technology-based modern farming, traditional solar terms remain relevant, especially in Chinese cultural and social life. Paying respects to lost loved ones remains an important practice on the day of Qingming, or the 5th solar term known as “Pure Brightness.” Other important seasonal rituals are also marked in different areas of China. The 24 solar terms have never faded away from the daily life of the Chinese.

Edited by BAI LE