The necessity of dialogue

When the poet Zhai Yongming stayed in Berlin during the year of 2000, she told me: “We Chinese understand more of the West than you Westerners understand of China.” How did she know this? Her kind of prejudice we can discover very often even among Chinese scholars, who might have some foreign language ability at their disposal.

Understanding is a process

Any understanding is not a result, but a process, a never-ending process. What one understands today has to be reflected tomorrow again in order to enlarge one’s knowledge. We shall not be able to reach an end by doing so. Thus, no understanding can be complete. It always will stay a kind of fragment, but this is a chance to enrich our limited knowledge. And this is good. Total understanding will turn the object of our reflections into a boring thing, and we will become an all-knowing God. We are nothing else than human beings, full of failures.

No hope then for an ideal dialogue between East and West? No hope then for an ideal? Just the opposite. As long as we belong to different cultures and systems, as long as we keep ourselves open for unheard stories and tales, for a new perspective, there’s a chance of mutual understanding. How is this possible? If we realize that there is nothing fixed in this world, that everything is open and depending upon our judgment, we might become well aware of changes taking place in our reception, and therefore, the things themselves. So we can say that except for our estimation, there’s always something else, and something different.

This is why contemporary French philosophy demands “Vive la France.” If we only ward off the other as other, we cannot develop. Any culture is the result of encounter. Only encounter allows social development. This includes the encounter of languages. It has long been said that the progress of a nation is impossible without translation work.

We can find this proved very clearly in China. Since her opening in 1978, she began to flourish because she started translating almost everything, and is now a nation of translation. The rest is obvious. China is now number two in the world, leading not only in the book market, but also in economics, etc.

Knowledge is not possible without encounter—the encounter of books, of translators, of authors, of readers. This “encounter” theory has, of course, its flaws. But in principle, it is true for early Great Britain or for late Germany. I just stated that there’s always something else, something that goes beyond our fixed judgment.

Attitude toward Confucius

Take, for example, Confucius. When I switched as a student from Latin, Greek and Hebrew to classical Chinese, I was told by my first teacher of that language at Münster University, there is nothing of interest, The Analects of Confucius. When I switched from classical Chinese to modern Chinese at the Beijing Language Institute during 1974-1975, Confucius was heavily criticized as reactionary, and as a rotten egg in the media and in daily life. That was finally the end for him, in my eyes. Though I had studied him very well with my supervisor at Bochum University, I regarded him as the most uninteresting thinker on Earth for two decades.

But 20 years later, it was a French philosopher and Sinologue who opened my closed eyes. He made use of hermeneutics as his method and explained, free from ideology, sentence for sentence, image for image, in The Analects. Francois Jullien created a totally new Confucius, a man of deep thought. Some years later, I discovered the German philosopher Otto Bollnow and his immense important book about the role of exercise in Chinese xi (literally “to study”) for becoming a real person. His study was written under Confucian influence. Suddenly, I turned from a Taoist to a Confucian.

Another example, I was not much religious anymore. Though the aim of the Jesuits was to turn China into a Catholic country, they more helped to change Europe to enter another kind of pre-modernity. Through their translations of Confucian classics, they started a revolution. Voltaire and others discovered, thanks to Confucius, that morals do not need religion as fundament, and that a state can be grounded on reason, and is not based on God anymore. Of course, this was not the aim of the Jesuits. They only wanted to present a Confucian doctrine that was convergent to Christian faith.

No single identity

We could go presenting one example after the other, for instance, with Martin Heidegger. He was a Nazi in the beginning of his career and might still have been even in the very end. But his philosophy, except for some minor traces in his thoughts, is philosophy for the world. Even in the life of a person whose morals are dubious, we can discover something else. The Jewish Hannah Arendt was once in love with Heidegger, and they met again after the Second World War in destroyed Germany.

How is this possible? Arendt was of the opinion: real humanity means that we make the world to the subject of our dialogue that would even include our opponents. Therefore, we have to notice that there’s always something else in something. What does this have to do with our identity? Many Chinese want to stay Chinese for the rest of their life, and want China to be forever Chinese the old way without big changes. This is impossible. According to The Book of Changes, the world is changing all the time. “Today” will be “tomorrow,” the other day, though it once represented “yesterday.”

Wherever we go, we see severe changes made. The German poet Schiller discovered in 1789 in Father Rhine, as he says, the “rapes of Asia.” The French poet Arthur Rimbaud claimed that, “I,” or a person, is another. We can understand this as we are not one, we are many. We are German and Chinese, and vice versa at the same time. There is no single identity. There are many different identities lifelong. In this respect, any scholarship is international. It is neither Western, nor Chinese.

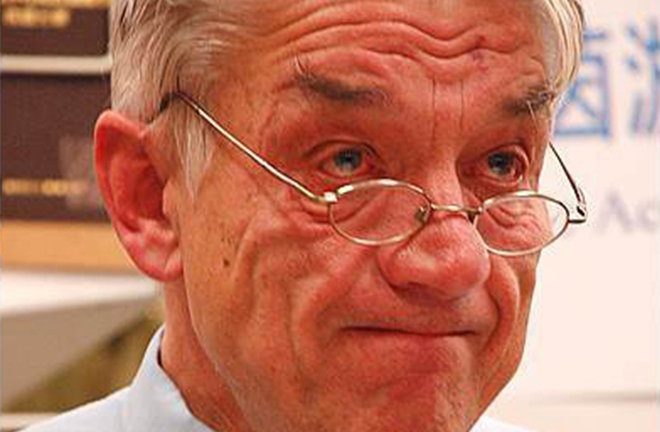

Wolfgang Kubin is lifetime professor from the University of Bonn, Germany; Chair professor from Shantou University. This article was edited from his paper submitted to the forum.

Edited by BAI LE