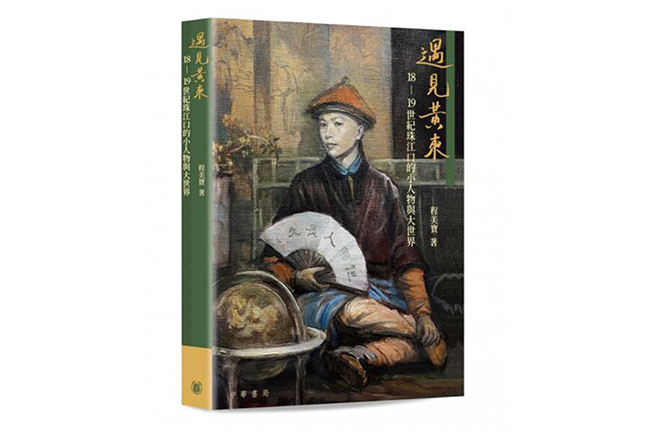

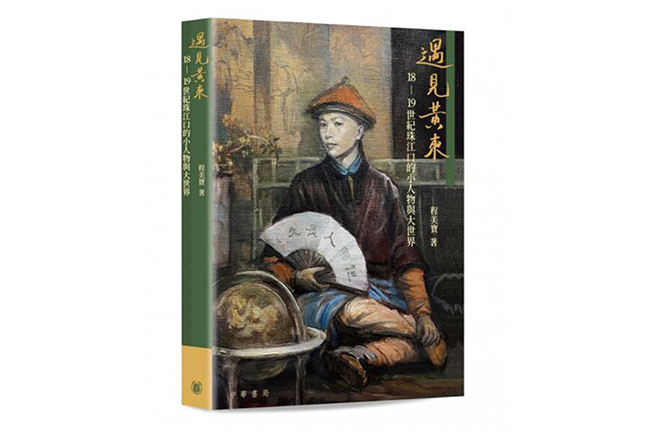

Ching May Bo’s 2021 book Encountering Whang Tong (Yujian Huang Dong), a recent work of global microhistory Photo: CHUNG HWA BOOK CO.

Microhistory emerged in the 1970s as an innovative way to research and write history. Into the 21st century, the historical approach has “turned global,” as global microhistory has become a new research trend. Some scholars argue that global microhistory is a product of global history’s impact on microhistory, a justifiable point. However, apart from the external impact of global history, microhistory’s inherent evolution should not be overlooked. Essentially, global microhistory is a logical outcome of microhistory’s advancing concern for large-scale, or “big,” history.

Since it began, microhistory has attempted to extrapolate the big history of each era and the world through the “small” history of an individual or a village, thus handling the relationships between micro and macro levels adroitly, and untangling links between small and big histories. Such a consciousness of big history eventually prompted microhistorians to take a “global turn” in the 21st century.

Emergence of microhistory

In the 1970s, some scholars began to question long-term structural history that dominated the Western history community, advocating for a history on smaller temporal and spatial scales. This marked the beginning of microhistory.

In his 1989 work Historiography and Postmodernism, Dutch intellectual historian Franklin R. Ankersmit spoke highly of three masterpieces in the field of microhistory, namely Montaillou: The Promised Land of Error authored by French scholar Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie; The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth Century Miller by Carlo Ginzburg from Italy; and Canadian American historian Natalie Zemon Davis’s The Return of Martin Guerre.

Ankersmit praised the three writings as models for “postmodern historiography,” saying that their research objects are not weighed down on the “trunk” or “branches” of a tree but expanding narrative’s growth on its “leaves.” They resist the macro-narrative of the trunk through the micro-narrative of leaves, in order not to fall into macro-narrative traps such as Eurocentrism, Ankersmit added.

However, microhistorians reacted strongly against Ankersmit’s claim. In an interview, Ginzburg made it clear that he didn’t agree with Ankersmit at all, saying he totally misunderstood those microhistorical writings. Ginzburg said that these works neither abandoned “evidence,” nor made a micro-macro opposition.

Davis also noted in an interview that although microhistory focuses on concrete and small-scale individual cases, it always tries to place them in the context of “total history,” in the hopes of drawing a universal conclusion beyond individual cases.

Global turn

Microhistory has remained conscious of big history since its beginning, which led to its “global turn” in the 21st century. Davis was the first to exemplify the shift with her 2006 book Trickster Travels: A Sixteenth Century Muslim Between Worlds. The book is about the story of North African diplomat Al-Hasan al-Wazzan who was forced to convert from Islam to Christianity in the 16th century, specifically, his strategies to survive and write in the worlds of Islam and Christianity, and North Africa and Italy. In so doing, Davis associated al-Hasan’s individual history with global history.

Following Davis, researchers of Chinese history, including Eugenia Lean and Henrietta Harrison, also turned to global history in their microhistorical studies. Lean’s Public Passions: The Trial of Shi Jianqiao and the Rise of Popular Sympathy in Republican China, recounts the story of a Chinese woman by the name of Shi Jianqiao who murdered the notorious warlord Sun Chuanfang in 1935, in retaliation for the death of her father. The highly sensationalized case was a means by which Lean zooms in on the rise and impact of popular sympathy in Republican China.

In recent years, Lean has examined Republican scholar and entrepreneur Chen Diexian, and the industry he founded, from a global perspective in Vernacular Industrialism in China: Local Innovation and Translated Technologies in the Making of a Cosmetics Empire, 1900–1940, in an effort to investigate the association between the boom of homegrown industrialism in China and the circulation of technology and knowledge worldwide.

Similar to Lean, Harrison’s microhistorical practice also experienced a global shift. She produced The Man Awakened from Dreams: One Man’s Life in a North China Village, 1857–1942 in 2005, which explores the predicament facing scholars when traditional society was transformed into a modern one through the protagonist Liu Dapeng, a provincial degree-holder in north China’s Shanxi Province.

Thereafter, Harrison turned her attention to a Catholic village in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, and wrote the book The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village in 2013. By unfolding the process of 300-years of interactions between the Catholic village in Taiyuan and the Roman Catholic Church, Harrison held that Western Catholicism was being localized in China amid the globalization of the church.

When writing the book, Harrison took notice of the stories of Chinese Catholic priest Li Zibiao, who was in government service in Shanxi during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), and the British man, George Thomas Staunton. Both served as interpreters for the Lord George Macartney embassy [the first British embassy to China] in its encounter with the Qianlong Emperor. Through the lives of the two cross-cultural interpreters, Harrison re-visited the Sino-British ties prior to the First Opium War of 1840–1842 and reflected on the relevance between the outbreak of the war and the disappearance of cross-cultural mediators. Harrison’s output, The Perils of Interpreting: The Extraordinary Lives of Two Translators between Qing China and the British Empire, was published in 2021.

The “global turn” has likewise appeared in Chinese academia of late, in the works of Ching May Bo, a professor of history at the City University of Hong Kong, and Liu Yonghua, a professor of history at Fudan University. In her 2021 book Encountering Whang Tong (Yujian Huang Dong), Ching investigated the connections between ordinary Chinese in the Pearl River Delta, south China’s Guangdong Province, and the Western world in the 18th and 19th centuries, with Cantonese Whang Tong, who can speak English and previously sojourned in England, as an example. Furthermore, she reexamined relations between the so-called “long,” and slowly changing 18th century and the “modern,” rapidly changing 19th century.

Liu’s new writing Cheng Yunheng’s 19th Century (Cheng Yunheng De Shijiu Shiji) is awaiting publication. Based on the small-peasant family of Cheng Yunheng in Huizhou, central China, it discusses changes in the space for action, subsistence models, and social networks of peasants as well as the relationships between the imperial court and villagers in the late-Qing Dynasty. Meanwhile Liu analyzed how these changes resulted from individual factors like rituals of life, national factors like the Taiping Rebellion (1851–64), and global factors such as fluctuations in the international tea market.

Domestically and overseas, early and recent microhistorical practices are all committed to uncovering the big history of each era and the world via the small histories of individuals or villages. While early microhistorical works tried to delve into regional and national histories through historical accounts of individuals and villages, recent attempts have reached out to global history through the small histories. The concern for a big history runs through the entire course of microhistory.

Implications for historical narratives

The “global turn” and the rise of global microhistory in the 21st century can help us reassess nation-state narratives. Compared with early microhistorical research, global microhistory features a broader research vision, as it considers global factors alongside regional and national features to study various impacts on individual and village histories. This is conducive for microhistorians to reflect on nation-state narratives from the perspective of global history.

In Encountering Whang Tong, Ching found that in modern China’s nation-state narrative, the First Opium War was considered a watershed moment between ancient and modern China, and a line dividing the long 18th century and the modern 19th century. However, through ordinary Chinese like Whang Tong and their contact with the outside world, Ching pointed out that many ordinary Chinese in the Pearl River Delta, Guangdong, had already “opened their eyes to see the world” for many years, even before scholar-officials like Lin Zexu and Wei Yuan embraced or called on Chinese people to embrace Western learning around the First Opium War. These ordinary Chinese had, in an extensive and in-depth fashion, interacted with people in the West and gained exposure to Western things since the 18th century. Therefore, the long 18th century and the modern 19th century are not entirely distinct from each other. The former can be regarded as an underlying current to the latter. Traces of many changes which took place after the First Opium War can be found in the 18th century.

The “global turn” in microhistory can also help us reflect on narratives of global history. In traditional global or world history narratives, Europe, the elite, men, and imperialism occupy the central roles. The new global/world history, emerging in the period from the late 20th century to the early 21st century, tries to dissipate the influence of various centric theories, particularly Eurocentrism, and shifts the focus to historical courses which transcend national, political, geographical, and cultural limits and have impacted all kinds of affairs across regions, continents, hemispheres, and even around the globe.

However, as Davis said in the article “Decentering History: Local Stories and Cultural Crossings in a Global World,” the historical agenda and categories of the new global history might still be “Western” and “Eurocentric,” and the sharp edges of social history, gender history and post-colonialism, typically pointing to the voices of marginalized groups and individuals such as subaltern classes, women, and colonized peoples, “are being ignored in the descriptions of large-scale interactions among civilizations, trading empires, and species.”

Thus, a new global history cannot eradicate biased perspectives. Be that as it may, global microhistory’s attention to individuals, particularly subaltern people, women, people in colonies, and non-Westerners can break the limitation, as proved in Davis’s Trickster Travels.

In short, microhistory’s “global turn” and the growing popularity of global microhistory will encourage reflections on global history narratives which center on Europe, the elite, men, and imperialism, and contribute to decentering global history.

Song Danling is from the School of Marxism at Huaqiao University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG