‘Double reduction’ entails longer compulsory education

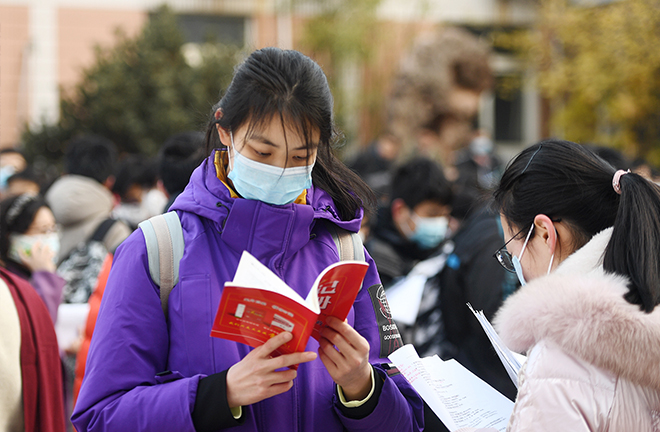

Students use every moment to review before taking a major examination at Nanjing No. 29 High School in east China’s Jiangsu Province on Jan. 15, 2022. Photo: CFP

In July 2021, the general offices of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council issued the Opinions on Further Reducing the Burden of Homework and Off-Campus Training for Compulsory Education Students. Known as the “double reduction” policy, the regulations were rolled out with the aim of helping to ease students’ academic burden and enhancing educational equity.

Since it was introduced, smooth implementation of the policy has been a great public concern. To ensure its long-term effectiveness, one of the widely accepted suggestions is to abolish the high school entrance examination, or zhongkao. This article argues that the fundamental solution should be to extend compulsory education from 9 to 11 or 12 years, as soon as possible.

Irrational competition

Education and examination are twin brothers. Since schools were created, education has been accompanied by various forms of examination. Examination can be used to test the extent to which students have mastered what they have learned, and assess teachers in terms of teaching abilities. Furthermore, as education is playing an increasingly important role in society, examination can also evaluate schools’ educational quality and the realization of their educational objectives.

From ancient times to today, the impact of examination on education, whether positive or negative, has been significant and profound. Take the Imperial Examination (keju) in ancient China, as an example. It was solely an examination system designed to select officials for the imperial court, without an immediate relationship to education. However, because employment in society and the promotion of scholars had become inseparable from schooling and learning, the Imperial Examination had a huge bearing on school systems and social ethos, affecting schools’ educational content, talent cultivation, teaching atmosphere, and intellectuals’ initiative to learn.

Any examination system is prone to burdening students with an excessive academic load. Eliminative examinations are crueler, and the zhongkao is one of these.

The zhongkao system was instituted to, first, assess the operational quality of schools dedicated to nine-year compulsory education within a province or city, and second, to split middle school students into general academic high schools and secondary vocational institutions.

With the quick popularization of higher education and students’ growing demand for higher-level education, the secondary role of the zhongkao is gaining ever more prominence. The fear of students being “degraded” and sent to vocational schools [which allegedly forebodes a worse future due to unsatisfactory vocational education systems in China] leads parents and students to highly value the zhongkao and engage in irrational levels of competition, causing an overwhelmingly heavy burden on students in compulsory education.

Currently the implications of the zhongkao for students and their parents have deviated far from the system’s original intention. At regional levels, the examination is like a narrow footbridge: those who succeed in crossing it will be allowed to further take academic pathways, while the rest will have to receive vocational education.

This differentiation attaches labels to students prematurely. At innocent ages of 14 or 15, some students are abandoned to the other side of society, which to some extent inhibits their creativity and adaptability, and undermines the fairness of basic education.

Compared with the college entrance examination, or gaokao, the channels to which students are distributed following the zhongkao are less diversified, whereas the gaokao will classify students into a wider range of institutions of higher learning.

Because the zhongkao comes earlier, students’ parents are more concerned with whether their children can pass it and make their way to academic high schools. Students themselves are anxious that they might be looked down upon by their peers for failing the critical examination. Consequently, “involution” in elementary and junior secondary education rages on across society. Students’ academic load becomes heavier and heavier, right from kindergarten, to primary school, and onto the junior high stage.

Objective conditions in place

China has popularized compulsory education for over a century, ever since renowned late-Qing Dynasty educators and thinkers Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao proposed making elementary education compulsory. Over the years, compulsory education was extended from junior primary school to senior primary school, and further to junior high school, gradually shaping the current nine-year compulsory education system.

Throughout the centennial history of compulsory education in China, universal education and compulsory education complemented each other. The universalization of junior education always preconditioned the implementation of compulsory education for a certain stage. To ensure the effects of universal education, laws and regulations were thereafter enacted to gradually define its compulsory, free, mandatory, and fair nature.

This history also proves that profound changes in modern Chinese society have brought about tremendous achievements in compulsory education, with the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 as the watershed moment. More than 50 years prior to this landmark event, Chinese people suffered from poverty, so the implementation of compulsory education was largely empty talk, whether regarding public discourse or policy.

In the second half of the history, under the CPC leadership, China has maintained prolonged stability in society, politics, economy, and education, providing strong guarantees for the popularization of compulsory education. In 2011, the strategic goal of universalizing nine-year compulsory education was realized in all respects.

Nonetheless, imbalances still loom large between county-level areas across the nation, and between urban and rural areas, posing challenges to improving the quality of compulsory education and comprehensively achieving equity in the field.

As such, the Education Inspection Committee of the State Council initiated a county-level evaluation on the balanced development of compulsory education in early 2013. By December 2020, all counties and county-level cities passed the basic national evaluation. In October 2019, the Ministry of Education started the evaluation of quality in compulsory education on the basis of balanced development.

These government efforts have basically set the stage for lengthening nine-year compulsory education. In 2021, the start of the 14th Five-Year Planning Period (2021–25) when China embarked upon the new journey to build a modern socialist country in all respects, all counties and county-level cities within each province and municipality progressively realized high-quality, well-balanced development of compulsory education on the county level, to bolster the construction of a strong nation with abundant human resources and great overall strength through high-quality basic education.

During the 13th Five-Year Planning Period (2016–20), provinces and municipalities across China successively executed three-year free education for the senior high stage. Some economically developed cities and counties practiced free education even earlier, providing necessary conditions for the majority of students to access senior secondary education.

According to data from the Ministry of Education, the gross enrollment rates for senior high schools reached 91.2% in 2020, which lays a solid foundation for the popularization of 12-year compulsory education.

Urgency

Objectively, however, all cities and counties are obliged by education policies to run both general academic high schools and vocational institutions for senior secondary education, and also must impose rigid rules on student quotas. As a consequence, some students who prefer to receive academic high school education are forced to attend vocational schools [due to their subpar academic performances].

This has invited discussions on two issues: Should China accelerate the extension of compulsory education from nine years to 12 years? Is it necessary to transform secondary vocational education completely into higher vocational education?

The answer to the first question is, objective and foundational conditions for 12-year compulsory education have already been in place in China. Moreover, universalizing compulsory education to the senior high stage is an inevitable trend for basic education in developed countries around the world, and also the objective requirement for building China into a prosperous, democratic, civilized, harmonious, and beautiful socialist country.

Given regional disparities in economic and educational development, cities and counties can gradually and by stages prolong compulsory education to 12 or 11 years, and elevate secondary vocational schools into higher vocational and technical colleges.

We interviewed educational officials in several counties and districts, who noted that school buildings and teachers have been equipped to popularize 12-year compulsory education, and it saves more human and financial resources to run general academic high schools than vocational schools.

The second question likewise has a definite answer. First, the parallel development of general academic high schools and vocational schools lags behind real social needs, calling for major reforms and innovation.

In 2002, the State Council promulgated the Decision on Vigorously Promoting the Reform and Development of Vocational Education, urging efforts to focus on secondary vocational education and maintain roughly similar sizes of vocational schools and general academic high schools. The policy indeed produced a great number of ordinary industrial laborers for China.

Two decades later, as China’s industrial levels rise and intelligent manufacturing technology advances, the previous model has been unable to meet growing demand for technical workers in high-end industries.

From the perspective of students and their parents, laborers who have reached the age of 16, but not 18, are minor workers according to the Chinese Labor Law. If teenagers of this age group enter the labor market, their physical and mental health, as well as personal growth, are very likely subject to negative impact. At the same time, this age range is the key stage for students to grow into mature youth, the prime time for them to learn basic knowledge and shape good moral qualities, and it is crucial at this age to receive senior high education. In addition, most parents hope their children can attend general academic high schools to obtain a complete education which includes basic science and culture.

Therefore, after realizing balanced development of the compulsory education system in county-level areas in an all-round manner, China should promote 12-year compulsory education for primary and secondary education stages step-by-step and terminate the division of junior and senior in high school, enforcing general senior high school education and elevating secondary vocational education into higher vocational and technical education.

This is vital to the construction of the schooling system with Chinese characteristics and the institutional guarantee for the long-term effectiveness of the double reduction policy.

Li Hongwu is a professor of education at Shaanxi Normal University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE