From fine brush to freehand style: the evolution of bird-and-flower painting

“Rock and Tree” by Su Shi of the Song Dynasty Photo: FILE

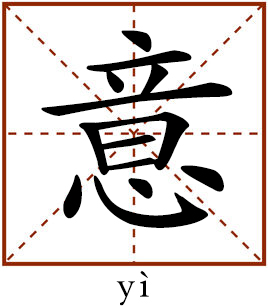

This common character refers to meaning, intention or significance. When combined with other characters, it forms diverse words and proverbs.

In 907, former Tang official Zhu Wen (852-912) forced the Emperor Ai of Tang to abdicate and then ascended the throne, changing the name of the nation to Liang. The founding of Liang marked the collapse of the Tang Empire and the beginning of an era of social and political upheaval, which was called the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-979). The hereditary nobility, which had been constant for centuries, finally broke down, leading to the decline of Tang Dynasty art, characterized by fine black lines, brilliant color and elaborate detail. A new distinctive style of art emerged.

From color-filling to black ink

During the long evolution of traditional Chinese art, painting was not valued as highly as calligraphy. Professional painters were called artisans rather than artists, because they were not recognized as real artists. Some artworks commissioned by scholars were not appreciated as well. However, the bias against painting was a blessing in disguise, providing less constraints and more opportunities for innovation. Early evidence of painters breaking away from the influence of traditional Tang art could be found in the bird-and-flower paintings of the Five Dynasties period.

Bird-and-flower paintings separated from decorative art to form an independent genre in the Tang Dynasty, during which the main method of painting was to outline figures with fine lines and fill them in with various colors, forming a realistic style. The works of Bian Luan, who lived in the reign of the Emperor Dezong of Tang (742-805), were representatives of Tang art. He was an accomplished painter, chiefly of birds and flowers in the realistic tradition. Take his work, “Pair of Phoenixes Facing the Sun,” for example. Bian outlined the exact figure of the phoenixes with fine strokes and painted them with bright colors, creating a sumptuous atmosphere. This approach was quite common in arts circles during the Tang Dynasty.

Although color was most important for fine art in the Tang Dynasty, black ink played a larger role in the Five Dynasties period, further developing in bird-and-flower painting. At that time, the most representative artists of bird-and-flower painting were Huang Quan (900-965) and Xu Xi (937-975). They were the masters of two schools respectively: The first school was led by Huang Quan (imperial painter). Huang inherited the essence of Tang painting with its emphasis on bright colors filling a meticulous outline (gongbi). The other school was led by Xu Xi (never entered into officialdom) and typically used techniques associated with ink-and-wash painting. Xu went beyond the reproduction of the natural appearance and grasped an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the vitality of birds and flowers. Xu was known for his unconventional use of black ink. Instead of using different colors and lines to depict the subject’s outward qualities, Xu created an impression of the subject’s texture, weight and coloring through different strokes of black ink. The other colors rarely appeared in his paintings, serving as supplementary decoration. Shen Kuo (1031-95), a prominent polymathic statesman in the Northern Song Dynasty, gave a brief introduction of Xu’s painting style in his masterpiece, Brush Talks from Dream Brook (Mengxi Bitan): “The paintings of Huang Quan, and those of his brother and his sons, were unique in that they put color on flowers. When they did so, they left almost no visible ink except for some light colors. Their brush stroke was creative and detailed, which made their flowers vivid and lifelike. When Xu Xi painted flowers, he used black ink and his stroke was rough. With a little red oil added to them, Xu’s paintings fully displayed the vividness and charm of the flowers.” However, none of Xu’s authentic works are preserved, leaving us no opportunity to appreciate his unique brushworks.

From fine brush to freehand

After Xu’s effort to integrate freehand style into his work, more artists started to explore new approaches in fine art. In the lead up to the reign of Emperor Shenzong of Song (1048-85), admiration for the ornate style of the Tang painting created by fine lines and rich colors was becoming outdated, as artists started to think about how to capture the vividness and vitality of birds and flowers rather than the reproduction of their figures. Two representatives of the Imperial Art Academy of the Song Dynasty, Cui Bai (1004-88) and Wu Yuanyu, pioneered the new trend by developing very different line styles.

Cui is known for his painting “Magpies and Hare,” also known as “Double Happiness,” in which he used surface lines to convey the fluffy sense of the hare. This technique that expressed the shade and texture via tiny surface lines instead of outlines was called cun ran. In terms of color, Cui used ink in different densities to create black, gray and white colors, forming an impression of the subject’s texture, weight and hue.

Towards the end of the Northern Song Period, the poet Su Shi (1037-1101) and the scholar-officials in his circle became serious amateur painters. They approached painting with the objective of expressing themselves. The painting “Rock and Tree” by Su Shi is an excellent model of freehand style. Its simple composition—a tree with bare branches distorted towards the sky like a struggling person, and a large angular rock with a whirlpool texture—seems to be confusing, but it can astonish people with its unique feeling, and some find it touching. From then onward, many painters strove to freely express their feelings and to capture the inner spirit of their subject instead of describing its outward appearance. The artists who advocated a freehand style idealized individuality of expression, using brushwork more to reveal the inner spirit of the subject—or of the artist himself—than the outward appearance. They suppressed the realistic and decorative in favor of an intentional simplicity and abstraction.

Reassertion of the fine brush

During the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), the development of bird-and-flower paint was less dramatic than that of landscape painting. At early times, the style of high reality succeeded, following the tradition of the art academy in the Song Dynasty. Late in the Yuan Dynasty, fine brushwork was again admired by the public. Such a trend might be associated with the restriction of scholars’ opportunities at court by the ruling Mongols, who distrusted the Chinese intelligentsia.

The only change was the substitution of ink-and-wash for filling in colors. Delicate fine brushwork was widely appreciated, while the freehand style promoted by Su Shi lost status. This reflected how the Yuan artists were somehow at a loss: Despite efforts to improve the traditional fine-brush technique, they were unable to achieve it because of self-imposed limitations. Their struggles between technical innovation and following tradition were depicted within their paintings, which seemed to be a bit awkward. For instance, in the painting “Bamboo, Rocks and Birds,” the Yuan painter Wang Yuan sketched the contours of bamboo with thin lines (Tang style), birds with dian ran (an innovative painting technique by adding little details), and rocks with cun ran. These elements, either traditional or innovative, looked good when they were considered individually. However, when integrated into a painting as a whole, there was an absence of harmony.

Among those artists of the Yuan Dynasty, Wang Mian (1287-1359) earned considerable recognition via his creative drawing patterns. When drawing the branches of a plant, Wang avoided using rough strokes so as to highlight their subtle curves. He also created a rhythmic balance between density and lightness through the arrangement of the leaves and flowers on the branches. What’s more, he optimized the composition by adding poetry on the artworks. Artists of the Ming Dynasty, greatly influenced by Wang Mian, came to explore more drawing techniques. The revival of the freehand style in the Ming Dynasty could be regarded as the continuation of Wang’s creative approach.

Song Wei is from the College of Literature at Bohai University.

(edited by REN GUANHONG)

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE