Hidden symbols in Chinese clothing

Wu Sha Mao was the standard headwear of officials during the Ming Dynasty. This painting portrays three Ming officials in formal dress with different Bu Zi.

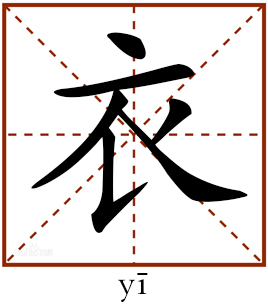

This character means clothing. Some anthropologists refer to clothes as “social skin,” indicating that what we wear has social significance. It is believed that clothes not only reveal some personality traits of the wearer, but also indicate a region’s history and identity.

As a crucial part of a region’s history and identity, clothing has important social significance, with different rules and expectations depending on the circumstances.

Public administration

Li is a fundamental concept in Chinese philosophy. It is difficult to be defined in other languages because Li embodies such a broad spectrum of meanings, including social norms, rituals, customs, rules of propriety and decorum. Nevertheless, one may understand the functions of Li through traditional Chinese clothing, which played an important part in guiding social behavior and promoting public administration in ancient China.

In imperial China, the rites of Li established a special bond between clothing and nations, namely attaching national prosperity to certain colors. This is similar to how the Wu Xing, or the Five Phases Theory—Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, and Earth—had corresponding colors, which played a key role in influencing many Chinese beliefs and customs. Though the color-to-element relationship has remained constant throughout Chinese history, the importance attached to a color changed from one dynasty to the next, particularly in relation to clothing.

Based on the belief that the five elements overcame and succeeded one another in an immutable cycle, the incoming dynasty believed that selecting a new dominant color was a sign of overcoming the one it supplanted. For instance, black was highly honored throughout the Xia Dynasty (2070?-1600 BCE) while the Shang (1600-1046 BCE), which supplanted the Xia, regarded white as the “king” of colors. The Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) held the color red in high regard, because it represented fire and thus was believed as the most powerful color. Then the emperor of the Qin Dynasty (221-207 BCE) wanted to show his superiority over the Zhou, emphasizing the use of black, or water, to “extinguish” the fire of the Zhou. Clothing of the Qin Dynasty was predominantly black.

During the periods of the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States, clothing was even regarded as a symbol of a state. That is to say, “one’s clothes” could be understood as “one’s homeland,” while a “conference of clothing” referred to a conference among states. Once a dynasty was supplanted by the other, there would be great changes in people’s clothing as well as the colors.

Clothing was also used to indicate individuals’ social rank or status, ranging from the administrators to those living at the bottom. One could tell the profession or social rank of someone by what they were wearing. For example, scholar-officials were also called Yi Guan, referring to the hat and gown worn by the gentry. Likewise, Bu Yi was used as a symbol of scholars not in government, because the material used in their clothes was bu, or cheap textiles, such as hemp and ramie fiber. Gentlemen were called Shen Shi, in which Shen was originally a sash worn around the waist as part of the formal dress.

In addition, clothing was associated with certain virtues, such as morality or national integrity. The proverb Liang Xiu Qing Feng, which meant a person’s sleeves were swaying with a soft breeze, is commonly used to describe an incorruptible official. This is because ancient Chinese officials often used their wide sleeves as pockets. Since some corrupt officials hid money in their sleeves, the one whose sleeves were filled with nothing but breeze were marked as honest and upright officials. Su Wu, a well-known Chinese diplomat of the Han Dynasty, was captured and then detained for 19 years in a foreign country. During the years of his captivity, Su refused to wear the foreign clothes and insisted on wearing the Han garments, expressing his loyalty to the Han Dynasty. In this case, clothing expressed patriotic sentiment.

Moral cultivation

Clothing can serve as a symbol of virtue or proper conduct. There were 12 elaborate embroidered items in the Mian Fu, a type of court dress for emperors to wear on formal occasions or ceremonies. Those items symbolized the 12 essential characters of a king. For instance, the “sun,” the “moon” and the “star” represented all the natural light ensuring a promising future; the “algae” was regarded as a form of purity or nobility while the “mountain” was a symbol of the emperor’s prestige; the “rice” reflected the king’s duty to feed his people and the “Fu,” a half-black and half-blue piece of embroidery, indicated the pursuit of goodness as well as the fight against evil.

Guan, the emperor’s formal headdress or crown with tassels in front, was considered the most symbolic item among the king’s garments. The 12 bunches of tassels hanging in front of the king’s eyes were called Bi Ming, implying no tolerance for bad things. Similarly, the hat tassels reaching down to the ears were called Se Ming, symbolizing a refusal to listen to vicious words or slander.

In the Ming Dynasty, headwear became a distinguishing factor of different professional ethics. An official in the most typical formal dress might look like this: His long hair was tied into a bun and covered with a Wu Sha Mao, a round hat made of black gauze with a pair of spreading wings attached behind it. Then came the You Ren-Pan Ling Pao, a closed round-collared robe with wide sleeves and a sash around the waist, while You Ren referred to the style of wrapping the right side over before the left. The whole garment was completed with a pair of black leather shoes. It was the mandarin square sewn onto the robe and its color that indicated the rank of the official wearing it. The mandarin square, also known as the Bu Zi, was a badge embroidered with detailed, colorful animal insignia.

Frequently, the Ming censorate officials who were responsible for monitoring the civil service wore hats called Xie Zhi as a badge of office. The Xie Zhi, a legendary righteous creature which settled disputes by ramming the party at fault, was used as a symbol of justice and law in ancient times.

Scholar-officials, influenced by Neo-Confucian thought, preferred the E Guan as their formal headwear. The E Guan was a tall hat with a round top symbolizing the sky, while the eight pieces of cloth sewn together on the hat resembled the Ba Gua or Pa Kua, a fundamental concept in Taoist cosmology. The wide brim of the hat was conceived as a symbol of tai chi. The E Guan, together with the Fang Jin, which was a type of flattop cap, formed the unique image of scholar-officials.

The socioeconomic differences between the upper classes and ordinary members of the public also affected clothing styles. While people with higher social status displayed voluminous clothes, ordinary people were only concerned with covering themselves. Therefore, commoners’ clothing was narrow and tight, usually including a black cotton-padded jacket, a blue skirt or trousers, white socks, black cloth shoes and a black soft cap. That was why ordinary people were called Duan Yi Bang as a whole at that time. Duan Yi referred to a type of short coat, which was suitable for physical work.

The ancient Chinese endowed every item of clothing with a certain meaning. In other words, every type of clothing served a certain purpose. In a sense, social order, as well as people’s conduct, were regulated by Li and other social norms or moral principles through what they wore at the time.

This article was edited and translated from Beijing Daily. Liu Zhiqin is a research fellow from the Institute of Modern History at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

(edited by REN GUANHONG)

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE