Birth, legacy of China’s first major modern fiction

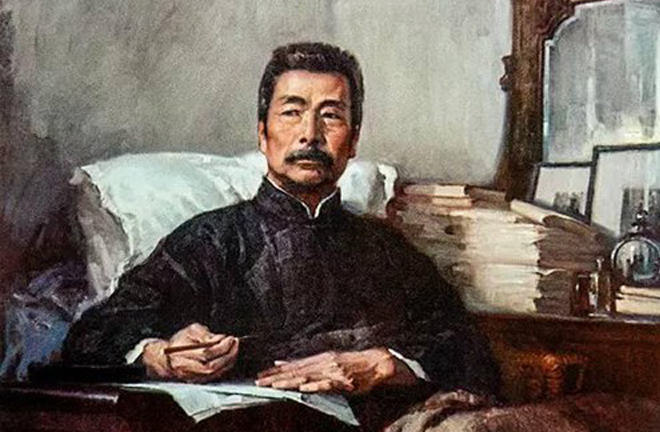

A figure painting of Lu Xun

A Madman’s Dairy was published in 1918. Lu Xun was 37 years old at the time.

In fact, Lu Xun’s childhood ended much earlier than his peers due to his family’s decline and his father’s early death. The pain left by this experience would gnaw at his heart for the rest of his life, but it also forced him to keep looking for a way out of the shadow.

Lu Xun’s encounters during the exploration told him that psychological suffering and mental illness were worse than poverty and disease and also more difficult to overcome. When he later became a writer, Lu paid attention to people suffering from poverty and disease. However, Lu was more passionate about persistently presenting his personal vision of their souls and values in the articles.

Lu Xun went to many places and tried different professions before the age of 37. From Shaoxing to Nanjing and from Sendai to Tokyo, he studied navy, mining and Western medicine. Finally, he chose the road of literature. His dream of becoming a doctor was shattered in a rural medical school in Japan. In class, he came across a news slide about the war between Japan and Russia in which a bound Chinese man stood in the middle flanked by many others. They had identical strong bodies and numb looks. Japanese soldiers were about to behead the bound one for his betrayal while the surrounded Chinese people came to watch the execution. Zhou was deeply shocked. Apart from national dignity, the scene brought back the special memories of his youth: numb look, cold heart, snobbish face and indifference to the weak; obedience to power and indifference to atrocities. These personal traumatic memories added to the worries about the larger crowd and the realities. Zhou abandoned the idea of becoming a doctor at 25.

Lonely people do lonely things. Zhou Shuren started to live at the Shaoxing Guild Hall in southern Beijing since 1912. He entered his middle age early by copying what he referred to as “useless” calligraphy on ancient monuments in the ancient room and his life remained the same without any waves.

The situation did not change until 1918. Qian Xuantong visited Zhou for many times. Qian and a group of people were organizing the New Youth magazine and he encouraged Zhou to write something. After being soaked in bitter loneliness for many years, the middle-aged Zhou hesitated to do so. However, Qian’s optimism and enthusiasm inspired him. Ultimately, Zhou agreed to write articles and his first work was A Madman’s Diary. The short story was published on May 15, 1918 and the name “Lu Xun” first appeared in Chinese history.

Why was the first work of fiction by Lu Xun filled with “crazy talk?” The beginning of his career as an author undoubtedly was a result of full considerations given his character, talent and especially his profound thoughts and well-rounded accumulations. It is destined that Lu Xun had thought over and over again to ponder how to invest his mounted power in the nets of words. And the words were as hard as heavy fists.

The first punch was A Madman’s Dairy. Indeed, it shouted out the first cry of modern China in an extraordinary way. In terms of content, the work exposed the hazards of the family system and moral codes as well as the “cannibalistic” nature of feudal values upon Chinese people. It invited the great movement for emancipating mind. Meanwhile, its “new and weird” artistic form created the way of appreciating modern short stories. It “seems to make people drowned in darkness suddenly see the dazzling sunshine,” Shen Yanbing wrote in his critic.

For the first time, the short story expressed the voice of a living man who spoke vernacular. At that time, Chen Duxiu and Hu Shi had called on to stop imitating language and writing style of ancient people, but the advocate remained an ideal. Lu Xun made the vision into a reality by completing the first vernacular short story though he hadn’t written any articles proposing literary transformation or revolution. Furthermore, the work adopted modern punctuation for the first time. Lu Xun frequently used question marks, exclamation marks and ellipsis and fully realized their functions in literary expression. These punctuations gave readers a hint of the meaning behind the words.

The more important thing was the content and value of the literary work. The “crazy talk” were filled with pun and symbolism that even the dullest readers could understand the fables hidden in the words. The incoherent absurd words of the madman then became aphorisms that indicate a profound mindset and wisdom.

A Madman’s Diary is not only the first work included in Lu Xun’s collection of short story Call to Arms, but also a preface of the writer’s all works, because the fundamental problems it raised continued to be discussed in his later articles, such as “cannibalistic” values, the attitude of bystanders and the relationship between enlighteners and the people to be enlightened. The issues were brought up and considered constantly, forming the traditions of modern Chinese mindset. In this sense, A Madman’s Diary is a classic work, but it is not a frozen specimen. It is an approach to modern Chinese literature. It is a door that leads people to a long, winding but great path.

(edited by MA YUHONG)

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE