Candles symbolize happiness, nostalgia in literature

Lamps and candles in Chinese literature symbolise hope, happiness and homesickness.

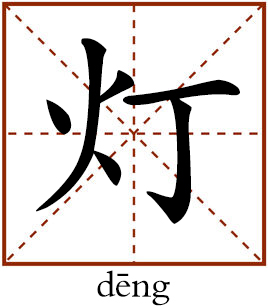

To illuminate themselves at night, ancient Chinese mostly used deng, meaning lamps or lanterns, or zhu, meaning candles. Red deng and zhu symbolize happiness. For those staying away from their hometowns, lamps and candles can also trigger homesickness.

Deng, meaning lamps or lanterns and zhu, meaning candles, are common icons in classic Chinese poetry and ci poetry.

Descriptions of deng and zhu can be found in references dating back as far as the Book of Songs. The song The Torches goes: “What hour is this time of night? It is far away from daylight. The torches are burning bright. Here comes our beloved king; Tinkling, tinkling the bells ring.” According to the Origin of Chinese Characters by Xu Shen in the Han Dynasty, zhu, which later referred to candles, originally meant torches.

Early description of lamps and candles were mostly about the extrinsic attributes of these objects. As history and literature evolved, lamps and candles gradually gained aesthetic attributes, evolving into typical symbols containing cultural connotations beyond themselves.

Radiating light and heat on dark nights and providing people with psychological comfort, lamps and candles naturally symbolize brightness and hope.

Wang Wei (c.701-761) once wrote “[It is] needless to worry about nightfall, there will always be a burning lamp.” Nightfall can easily trigger a person to lament the setbacks suffered during one’s life. However, a lamp illuminating weak but stable light comforts the poet, providing him with confidence and hope.

Dai Shulun (c.732-c.789) wrote “I seek temporary lodging at an old temple. A lamp shines in the deep and serene temple courtyard.” These verses depicted the heart of a drifting traveller warmed by the weak lamp in the darkness.

Lamps and candles also symbolize warmth and joy. Red lamps and candles are used on joyous occasions. The warm candle fire and hazy light and shadows interweave with the dim light of the night, forming a beautiful and comforting picture. Du Fu (712-770) once wrote “Too much joy triggers sadness about my gray hair. I fall in love with the red light of the candle in the dead of night.” The sense of aging is magnified at night. However, the red flickering candle fire warmed up the entire aesthetic space and the sad feelings are also eased by the images of lamps and candles.

In ancient times, people’s space for activities shifted from outdoors to indoors at night. Lamps and candles as necessities served as witnesses to family bonds, love and friendship. Ancient Chinese read books, tailored and sewed clothes for loved ones by lamplight or candle fire. A girl falling in love rubbed her ears against a boy’s shoulder by the lamplight. Friends had conversations deep into the night by the candle fire. The beauty of the warm color, flickering fire and blurred light and shadow corresponds with the aesthetic idea of classic Chinese poetics—gentleness, sincerity, grace and self-restraint.

On the other hand, lamps and candles were also sometimes used as symbolism of the tragic natures of human life—its finite nature, humbleness and transience. In this context, a burning candle is itself a gesture of confronting and fighting against darkness. A candle burns itself for the sake of others, making itself a cultural symbol of sacrifice and dedication to one’s mission.

An intense attachment to one’s hometown is part of China’s national ethos. In ancient times when transportation was underdeveloped, the nostalgia of a person who was on a long journey or stayed far away from his hometown was easily magnified when night fell. The warm light of the candle fire would trigger one’s sense of belonging toward his family or friends in his hometown. A poem written by Nalan Xingde (1655-1685) goes “A road of mountains; a road of waters; a journey toward the Yuguan Pass I am on. Deep into the night, lanterns in the thousands of tents are still on.” His job as an imperial bodyguard of Emperor Kangxi left him little time to reunite with his family, tent lanterns here carried his longing for his family and friends.

Li Siyuan is from Beijing Normal University.

(edited by CHEN ALONG)

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE