Mei in traditional Chinese ink and wash paintings

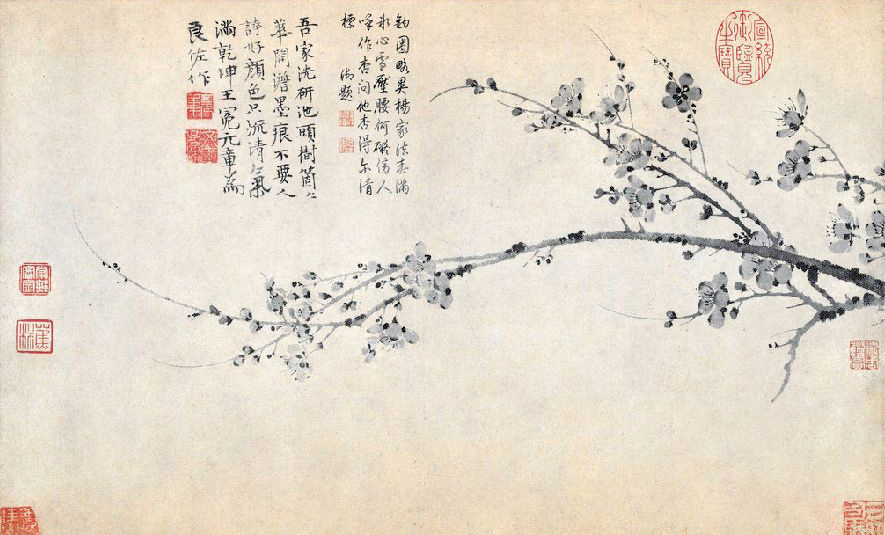

Momei Tu, a painting of mei, or plum blossoms, with only black ink, by Wang Mian in the Yuan Dynasty

In the Chinese history of art from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) to the Five Dynasties (907-960), mei, or plum blossoms, were either the contrasting settings in figure paintings or grouped with other plants or flowers. It was not until Song Dynasty, that mei paintings became an independent category in Chinese art.

The Song Dynasty represented one summit of Chinese aesthetics, the art of which features an emphasis on the “yun” or “lingering charm,” which can only be sensed, but not be expressed in words.

The charm of mei in traditional Chinese paintings may be roughly summarized as the harmony between thought and the environment. There are several methods of sensing this harmony.

Of all the flowers, mei is not particularly gorgeous. However, mei blossoms are colorful while having the auspicious connotation of heralding the coming the spring. Therefore, mei became the best subject for the court painters to demonstrate their painting skills.

However, mei paintings using only black ink became popular outside the imperial court. Shi Zhongren, a Buddhist monk, was believed to be the first to paint mei in this style. He once wrote a poem to demonstrate his painting ideas, saying that the light ink painting was marvelous since the mei flowers were not tainted by colorful powders. Perhaps his emphasis on the unadorned beauty of mei in ink and wash paintings came from his Buddhist meditation.

Wang Mian of the Yuan Dynasty was another master of the black ink mei paintings. He created the technique of painting with ink while dotting mei with red, bringing out a visual impact that was gorgeous but not garish.

The Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou, who were eight artists in the Ming and Qing dynasties, were also outstanding at painting mei. Most of these eight artists were literati who had sought to distance themselves from government affairs. This made them bolder in artistic expression and showed wild and bleak features in mei painting.

The ink painting of mei with black ink on white paper creates an artistic pattern in Chinese paintings that features the pursuit of purity and the philosophy that the greatest beauty is the simplicity.

In the history of Chinese thought, the Song Dynasty was known for the harmonious coexistence of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism. The I Ching, which was the quintessence of traditional Chinese metaphysics, was also prosperous in that era. This philosophy of the I Ching impacted both the scholars and painters of that time, creating the unique cultural phenomena of meditating on the philosophy of Yi (change) in mei flowers or trees and following the philosophy of Yi when painting mei.

Mei was generally considered the flower with the purest smell and a product that embodied the essence of heaven and earth. Therefore, mei best reflected the philosophy of Yi, which represents the combination of yin and yang forces and ever-lasting vitality.

A theory states that mei flowers followed the laws of the heaven while mei trees followed the laws of the earth. Therefore, specific parts of the flowers or the trees, for example, the roots, branches, calyx or stamen, all respectively had a perfect number that should be followed when painting mei.

This extreme dogmatism was followed by court painters which was not appreciated by some artists outside the court. Rejecting this dogmatism, Yang Wujiu (1097-1171) painted mei with his own style, which was once despised for being “rural” mei by the Emperor Huizong (1082-1135). Yang was not discouraged and continued the pursuing of “rural” mei painting. Inspired by the idea of Taichi, Yang later created the technique of painting mei flowers with empty circles, bringing about profound reform in the painting of mei in Chinese history.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE