Growing migrant student population fuels inequity

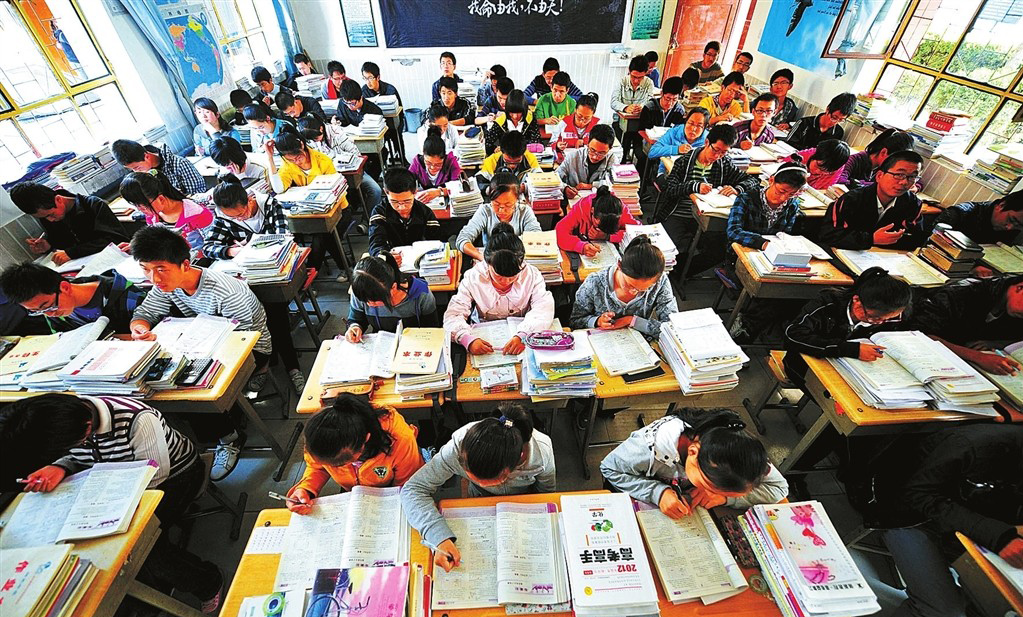

Students are busy preparing for the college entrance examination at Shenmu Middle School, Shenmu County, Yulin City, Shaanxi Province. The massive urban-rural educational migration changes the stereotype that rural schools apply exam-oriented education and lag behind urban schools that are believed to exercise quality-oriented education.

In the 1960s, American sociologists Peter Blau and Otis Duncan introduced status attainment theory, which states family background is a significant factor in determining a person’s ability to attain a position in educational and occupational hierarchies. Since then, many scholars have built on the model and developed a comprehensive theory on how educational expectations, parental social background, family wealth and educational system affect acquisition of education opportunity.

In the early 1990s, temporary educational migration began to emerge in China. In practice, migrant students keep their records where their households are registered but attend school elsewhere in hopes of obtaining better chances at getting higher education. Such a phenomenon is defined as “to-and-fro” education.

In addition to children who move to cities with their migrant parents and enroll in urban schools, migrant students here also can be used to describe those urban students who move to study in small cities or towns to improve their scores. In this article, the term “migrant students” refers to the latter, and the focus will be on mobility from urban centers to the counties and towns.

This article will examine the outcomes and influence of temporary educational migration of urban middle-class families whose household incomes stand at approximately 200,000 yuan per year. The article looks at children who have failed to gain admittance to top high schools in cities, so they elect to study at first-class schools in small cities and towns.

A town-level key high school in the east coast of China was chosen as a sample to study the phenomenon. It is quite representative because 52.3 percent of students in this school are migrant students.

Squeezing out rural students

Urban families take advantage of their socioeconomic resources to give their children an edge in education, reducing pressure in college entrance examination or squeezing out some competitors along the way. In small cities or towns, the social connections, status and wealth of urban families contribute effectively to improving their children’s academic performance.

In some cases, such a special group accounts for almost half of the class, directly or indirectly diminishing the opportunities of rural students.

To start with, all schools have an admission quota set by the departments of education, but when it comes to students who study on a temporary basis, each school has some wiggle room. The competition for acceptance is extremely fierce, and parental social resources play a big part. Compared to urban students, those from villages are often on the losing end.

Also, the capacity and public resources of the schools are limited. Urban transient students take up vacancies, leaving fewer for rural students.

In addition, there are hidden side effects from the influx of urban migrant students, including the increased time and energy investment of teachers. Again, when more attention goes to urban students, local students are bound to be neglected.

Finally, rural families have low risk-bearing ability or low expected returns on education, so some parents advise their children to exit the competition too early. In fact, college fees are sometimes not their primary concern, whereas we worry that relative opportunity cost is too high. Such drop-outs are not the result of obvious barriers, but are indeed choices out of careful reasoning and desperation.

Satisfactory results

The urban-rural mobility reflects the positioning and planning of urban parents for their children’s education in a special period of time.

High school is the final stage before higher education and parents face a range of choices in choosing the right school. Without doubt, they intend to minimize risks and gain maximum control over their children’s future. At this crucial moment, urban families do not hesitate to exploit their economic, social, cultural, and emotional capital to ensure they give their children the best chance. In most cases, the experience of previous migrant students is vital for those who look for schools for their teenage kids.

Though parents need to pay extra fees for their children to study at another school and spend time and money to visit, they still think temporary migration is a good choice relative to cost of out-of-school tutoring if they were to attend a lower-quality school in the city.

According to the sample research, urban families see their children’s scores improve greatly after enrolling in town-level schools, despite the fact these students are outsiders and fall behind locals at first. They are put in the center of attention because of their parent’s social connections. Such an “expandable effect” of their resources provides a practical basis for urban families to embark on a most convenient and plausible educational path.

The survey of 304 urban migrant students showed that most parents are satisfied with their choice of town-level schools as well as their children’s scores, while 82.7 percent students say they are “happy” or “fine” with their college entrance examination results. Improvement on their school work gives them a better higher education, thus making the competition and class differentiation begin at an earlier stage.

Stereotype

Urban-rural mobility not only characterizes the educational pursuit of individual families but also highlights the controversy between quality-oriented education and exam-oriented education. For many, rural education lags behind by encouraging around-the-clock studying and endless exercise. In comparison, urban schools, featuring cutting-edge teaching concepts, excellent facilities and colorful extra-curricular activities, are fine examples of quality education.

However, the reality speaks quite differently. The success of key town-level schools cannot be entirely attributed to their emphasis on scores, while urban schools might not truly implement quality education, either. So is born the massive urban-rural educational migration.

To say the least, the goal and model of education are at large derailed, and the boundary between quality-oriented and exam-oriented education is blurry. At its roots, the long-standing urban-rural dual system leads to an unbalanced allocation of educational resources. In this light, the discussion of two types of education models is not a simple education phenomenon. Rather, it is a profound social issue.

It can be said that the pursuit of utility values of education in current society, government departments, schools, and individuals has steered us away from the true meaning of education. It also causes chaos in the sector, such as improperly charged fees and gaming the system as well as unbalanced distribution of educational resources and opportunity.

According to the classical understanding and interpretation of social dysfunction, we can conclude that the current education system is in a period of dysfunction. The key to addressing such an issue lies in the fair distribution of educational rights, interests and resources.

Regardless of how policies change, most urban families—in particular middle- and upper-class families—have an advantage. Also, it is worth noting that the temporary educational migration occurred first in the early 1990s and it continues today. Therefore, such a phenomenon is quite entrenched.

Stuck in the middle of compulsory education and higher education, general secondary education resource distribution in China faces a “double dual system:” urban and rural average schools, and key and non-key schools. In average high schools, urban schools usually have favorable conditions in terms of resource allocation. However, when it comes to key and non-key schools, the former often receive heavy investments.

As a quasi-public product, secondary education should allow some freedom for schools and students, but it cannot allow too much market influence. Consequently, its resource allocation is by all means complex.

In the meantime, because of the sensitivity of higher education, government attaches more attention to it and more specific management is in order. High schools, on the other hand, are more vulnerable to external influences, so families can pay a small price to get what they want, which is why the phenomenon can evolve in secrecy without much public awareness.

The educational inequalities brought by migrant students are no longer an abstract theory but a concrete dilemma. Only through further study on specific education reforms and relative interests can we conduct more specific, comprehensive, grounded and rational thinking as well as policy adjustments to address the issue.

Ji Chunmei is from East China Normal University.

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE