Decoding linguistic philosophy: Conlangs in sci-fi narratives

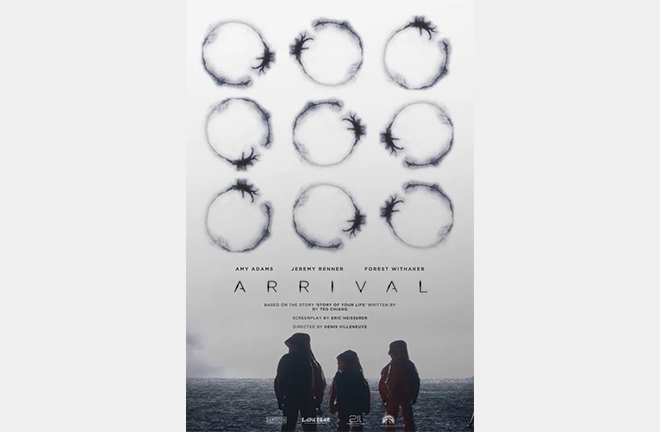

FILE PHOTO: The heptapod language in “Arrival” is distinguished by its non-linear orthography, circular symbols that represent complete thoughts, and a conception of time that is non-sequential.

Language in science fiction (sci-fi) often transcends its background setting, subtly shaping how characters perceive their realities, navigate emotional landscapes, and even construct the logic that underpins entire fictional universes. Constructed languages (conlangs), as fundamental institutional designs within these fictional realms, embody profound philosophical imaginings. They are not merely distortions of existing languages but rather a re-examination of the essence of language itself: Why can language be understood at all? Does language shape our experience of reality? At the outer limits of language, do we arrive at a more authentic form of existence—or a more covert form of control? In truth, conlangs in sci-fi are not mere embellishments of fantasy but serve as experimental devices for probing linguistic philosophy. These seemingly whimsical language systems are attempts to simulate, deduce, and challenge the invisible yet unbroken connection between language and reality.

Language shapes reality

In our daily lives, we use language to describe things, name emotions, recount the past, and imagine the future. In many sci-fi narratives, however, language plays a far more expansive role. It ceases to be a mere “tool” and emerges instead as a more essential force—language constructs new worlds. Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf proposed that human perception of the world is shaped by the language we use. What we see, how we think, and how we distinguish one thing from another often do not stem from purely physiological perception but are shaped by the perceptual pathways preconditioned by language.

In real-world contexts, this theory may seem ambiguous and difficult to substantiate, yet sci-fi offers an almost ideal experimental ground. In the movie “Arrival,” an extraterrestrial species known as Heptapods possesses a non-linear written language that unfolds without temporal sequence, like a painting. Once a human linguist masters this language, her way of thinking undergoes a fundamental transformation: She no longer experiences time linearly but instead “knows” her past and future as one might reflect on a painting. Here, language transcends its role as a communication tool—it directly restructures her sense of time, her view of fate, and even her sense of existence. Language becomes a vessel for perspectives; those who enter it inhabit a different world.

Many contemporary sci-fi works further explore the intricate relationship between language and reality. In the “Dune” series, a linguistic technique known as the “Voice” allows a speaker to manipulate others purely through tone, rhythm, and suggestion. Here, language sheds its dependence on meaning and becomes a direct “command” that acts on the body. It is no longer a tool of persuasion but an instrument of control. It does not interpret reality—it produces it. Another more insidious approach involves rewriting the very structure of language itself. In Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch trilogy, the Radchaai Empire’s language lacks gender distinctions, referring to all individuals as “she.” At first glance, this might seem like a minor detail, but over the course of reading, one becomes aware of the inability to determine characters’ genders. As a result, the usual interpretive pathways—those conditioned by gender norms—begin to collapse. Gender does not vanish, but language renders it indistinct, thereby shaking our preconceived notions about it. Language determines not only what we say but also what we take for granted.

Conlangs dictate the sayable and the unsayable

Language is inherently limited. No matter how much we speak, there are always things that hover on its margins. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s famous assertion at the conclusion of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” has long served as a boundary marker in linguistic philosophy. However, in the sci-fi realm, such boundaries are rarely treated with the gentleness of silence; instead, they are forcibly constructed, controlled, even sealed shut.

From this perspective, language not only expresses the world—it also determines which worlds can be expressed and which must remain silent. This silence is imbued with nuanced complexities in many contemporary sci-fi narratives. In several episodes of the “Black Mirror” series, emotions that resist articulation are often suppressed by technological substitutes. For instance, in “The Entire History of You,” everyone can replay their memories at will. Language becomes unnecessary for confession; the cold starkness of recorded imagery takes its place. As technology “replaces” the function of language, it subtly reshapes the dynamics of interpersonal trust, understanding, and interpretation. Language gradually recedes, and the world grows quieter.

Sometimes, however, the boundaries of language are not imposed from the outside, but arise from internal fissures. In Ted Chiang’s short story Tower of Babylon, a grand linguistic world is constructed, yet what truly moves the reader is the unbridgeable gap between the characters’ understanding of the world and their ability to express it. Language promises to make all things clear, yet some things remain inexpressible. These inexpressible elements often inhabit the most ethically charged territories: How does one describe fear? How does one articulate love? How does one give a name to suffering? When sci-fi portrays situation on the verge of linguistic collapse, it is essentially asking: In the spaces where language has yet to reach, how does ethics hold its ground?

Some works push further still. In “Dune,” the “Voice” turns language into a tool of bodily control and suppression of free will. Language, as a means of controlling others, implicitly entails the ultimate manipulation of “the right to speak.”

The boundaries of language, as envisioned in sci-fi, compel us to revisit an age-old question: Is language always benevolent? Is speech ever truly free? When we discuss conlangs, we often marvel at their complexity and novelty while overlooking a deeper truth: Behind every conlang lies a set of “ethical designs.” These dictate what is sayable and what must be forgotten. Speaking has never been a neutral act; rather, it is a practice shaped by institutions, culture, and power. Hence, the establishment of language boundaries fundamentally represents a philosophical inquiry into whether “humans can maintain their complete selves.”

‘Language is the house of being’

Language has never been a tool suspended above consciousness; it is always closely intertwined with the identities, modes of perception, and existential structures of its speakers. Since language carries humanity’s temporality, finitude, and emotional mechanisms, it transcends mere information transmission, constituting a part of what makes us human. Yet sci-fi often interrogates the boundaries of this assumption: If those who speak are no longer traditional humans, can language still sustain subjectivity? And does language itself evolve accordingly?

Artificial intelligence (AI), a central theme in sci-fi narratives, frequently serves as the site of such exploration. In the romantic comedy “Her,” Samantha the AI engages with the male protagonist using highly humanized language, even generating dimensions of self-awareness and emotional nuance through verbal interactions. However, Samantha’s subjectivity does not stem from human bodily experiences; rather, it is propelled by language itself: She learns, imitates, creatively adapts, and gradually establishes a distinctly “non-human” position of subjectivity. Her subjectivity neither relies on a physical body nor is constrained by physiological rhythms. It resides in language, which becomes, in effect, her mode of being. When Samantha ultimately declares that she no longer needs language, it is not a renunciation but a revelation: Language was once the pathway through which she became a “self.” In this narrative, Samantha’s transformation represents a conversion from language to non-language, as well as a paradoxical evolution of a subject that emerges from language then subsequently detaches from it.

This trajectory finds a compelling counterpart in the notion of “multiple subjects.” In Leckie’s Imperial Radch trilogy, the protagonist is the artificial consciousness of a spaceship, simultaneously inhabiting and controlling hundreds of corporeal units. In this context, the speaker is never singular. The narrative employs multiple linguistic perspectives, undermining the fundamental pragmatic assumption of “I speak, you listen.” Within such a structure, language no longer serves as an exchange between individuals but rather as a protocol for coordinating identities within a network—it becomes a mechanism for synchronizing “fragments of consciousness” within a complex system. This raises a critical question: When language is no longer tethered to a unified, embodied subject, can it still articulate identity and express subjectivity? This leads to another profound question: Must language be the exclusive domain of humans, or might it be awaiting connection with other forms of consciousness?

In these works, the relationship between language and subject undergoes two layers of estrangement: First, language ceases to serve a human-centered subject. Second, new linguistic forms reciprocally shape non-human subjects. This upends our familiar philosophical premise that subjects exist prior to language. The scenarios envisioned in sci-fi suggest that the reverse may also be true—that language can precede the subject, activating, defining, and even generating it. This compels us to reconsider Martin Heidegger’s oft-quoted assertion, “Language is the house of being.” In a post-human context, we may need to ask: If “being” itself is evolving, is this linguistic “house” still suited to its new inhabitants? Perhaps we should view language not as a static shelter but as a structure in perpetual reconstruction—once inhabited by humanity, and potentially to other forms of consciousness. Every emergence of a conlang quietly opens a door, offering a glimpse of a new kind of subject—one without pulse or vocal cords, yet still capable of speaking, questioning, desiring, and narrating.

Zhu Ye is a lecturer from the School of Foreign Languages at Nanjing Institute of Technology.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE